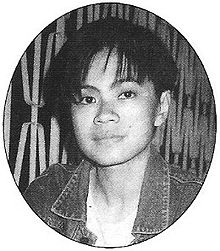

Written by Wing-Fai Leung.

The Taiwanese writer Qiu Miaojin (1969-1995) committed suicide in Paris aged twenty-six, leaving behind a handful of short stories and two full length novels, Notes of a Crocodile (1994) and Last Words from Montmartre (1996). Both novels are now recognised as part of the lesbian literary canon. They have recently been translated into English (by Bonnie Huie and Ari Larissa Heinrich respectively) and published by the New York Review of Books (NYRB) Classics. The series includes only four modern and contemporary Chinese literature, the other two being Eileen Chang’s works. Notes of a Crocodile has just been added to the long list for the 2018 PEN Translation Prize.

Qiu graduated from National Taiwan University and left for graduate study in Paris in 1994. At one point, she studied under the French feminist scholar Hélèn Cixous, which greatly influenced the writing of Last Words from Montmartre. Qiu was fascinated by modern European literature and culture, and she worshipped the films of Andrei Tarkovsky and Theo Angelopoulos, and the Japanese avant-garde writer Kobe Abe’s works. Reading Notes of a Crocodile and Last Words from Montmartre in sequence allows us to examine the coming of age of queer identity politics in Taiwan through the 1990s.

Her works also reflected the cosmopolitan interests of avant-garde intellectuals. Like other public figures who died tragically young, Qiu has been mythologised. It was widely speculated in the Taiwanese media that she stabbed herself to death with a kitchen knife. She was therefore thought to have been ‘inspired’ by the 1970 suicide of another Japanese author Yukio Mishima by seppuku, the ritualistic death by disemboweling.

Qiu was writing at a time when the budding lesbian scene in Taiwan was still predicated on the T/po (tomboy/butch and femme) binary. The author clearly struggled to identify with this binarism while contemplating her own lesbian identity, as her work continues to problematise the discursive boundaries between gender and sexuality

In an article for Kyoto Journal, Bonnie Huie writes that Notes of a Crocodile is ‘intended to be a survival manual for teenagers, for a certain age when reading the right book can save your life’. The protagonist/narrator Lazi tells a coming-of-age story as a lesbian in Taipei. Lazi has since become the synonym for lesbians in Chinese (Lala in China). The protagonist’s friends epitomise the heady bohemian life of the time; they are rich, slacker and gender fluid.

The novel documents a new sensibility that marks the end of the Martial Law period (1949-1987). It also reflects student politics, which were at the time heavily influenced by the Wild Lily Movement in 1990: a six-day student demonstration for democracy. Although the prose may seem immature in places, it is Qiu’s queering of the central protagonist, and her experimentation with genres – part diary and part fiction with aphorisms – which betrays the author’s non-conformative intention. The crocodile in the novel, disguised as human, is a euphemism for the isolated and ostracised queer body. At the same time, there are also sections that directly question normative gender identities:

“It’s based on the gender binary, which stems from the duality of yin and yang, or some unspeakable evil. But humanity says it’s a biological construct: penis vs. vagina, chest hair vs. breasts, beard vs. long hair. Penis plus chest hair plus beard equals masculine, vagina plus breasts plus long hair equals feminine. Male plugs into female like key into lock, and as a product of that coupling, babies get punched out.” (p.4)

Qiu was writing at a time when the budding lesbian scene in Taiwan was still predicated on the T/po (tomboy/butch and femme) binary. The author clearly struggled to identify with this binarism while contemplating her own lesbian identity, as her work continues to problematise the discursive boundaries between gender and sexuality:

“As I naturally love women, the women I love do not need the prerequisite of a sexual orientation for loving women… I don’t believe that my desire for, or union with, women is all that different from when a “man” wants a “woman.”” (Letters from Montmartre)

The intense emotional letters contained in Last Words from Montmartre were written as though Qiu had a premonition about her own death, with a dedication which appears unbearably sentimental and yet nakedly honest,

For dead little Bunny

and

Myself, soon dead

The letters address the reader directly as ‘you’, the lost love object Xu, who is supposed to have been in a three-year relationship with the author’s alter ego Zoe and who betrayed her. The bunny in question was a pet adored by the couple, but its death two months prior to Qiu’s suicide had devastated her. With this dedication, Qiu challenges us to engage with her through the powerful and painful journey leading up to her suicide, which will come to symbolise the rising queer consciousness in Taiwan. Her direct engagement with non-heteronormative sexualities heralds in a new era in terms of Taiwan queer literature where earlier proponents include Pai Hsien-yung. Pai’s Crystal Boys (1983) depicts young gay runaways in a deeply conservative society.

After her death, the Taiwanese media hailed her as a martyr for the gays and lesbians in the country. The writer and scholar Ji Dawei declares that without Qiu, LGBTQ community would not have been united. Evans Chan, the Hong Kong born, New York based independent filmmaker made a documentary about her for the government broadcaster, Hong Kong Radio Television as part of its Chinese authors series. With the recent publication of her novels by NYRB, Qiu’s influence has been confirmed and extended beyond Taiwan, introducing global readers to modern literature from the island nation, which rarely elicits much interest from the publishing world in the West.

Qiu made history by her open declaration of a lesbian identity – as though she was coming out for the queer community in Taiwan – ‘I am a woman who loves women.’ (Notes of a Crocodile, p.8) In the following two decades, the LGBTQ movement in Taiwan has become a formidable force. At the end of Chan’s documentary, Cixous states that Qiu left her aesthetic creation when she died, and invented life in death, and life after death.

Wing-Fai Leung is Lecturer in Culture, Media and Creative Industries, King’s College London. She has researched the film and media industries in China and Hong Kong, diversity in cultural and creative labour, and work and labour in the ‘gig economy’. She has published in Information, Communication and Society; Sociological Review; Asian Ethnicity and Journal of Chinese Cinemas; and is currently completing a manuscript on gender and digital entrepreneurship in Taiwan to be published in 2018. Image Credit: CC by Mirage D.Y./Flickr.

‘Qiu has been mythologised.’ By the media only? Or by the LGBTQ community also?

Qiu deliberately chose death over life for herself. Considering this, it is a stark claim indeed that Qiu ‘invented life in death, and life after death’, comparable to the claim that Jesus Christ has bestowed eternal life on his followers by suffering violent death himself. Doesn’t such a claim qualify as a myth par excellence?

Doesn’t a dedication like ‘For dead little Bunny and Myself, soon dead’ hint at a mental state that renders Qiu too delicate for life? Any way, to claim that the dedication ‘appears unbearably sentimental’ falls short by far in my reading.

Doesn’t queer theory state that there is nothing natural in gender roles, sexual orientation and identity? So, how could Qiu who wrote ‘I naturally love women’, be considered as ‘coming out for the queer community in Taiwan’? Is this another myth in construction?

Qiu said of herself ‘I am a woman who loves women’, such identifying herself ostensibly a woman. How does this statement cohere with the claim that she ‘directly question[s] normative gender identities’?

To differentiate between woman and man makes sense only in a binary system, that is a ‘gender binary, which stems from … some unspeakable evil’ as Qiu claims. And to proclaim that one is a woman (a non-man) who loves women reinforces the normativity of the gender system because otherwise the proclamation would be inconsequential. However, shattering binarity makes the normativity fade away. To proclaim that I am a person who loves persons could do the trick.

When Qiu writes ‘Male plugs into female like key into lock, and as a product of that coupling, babies get punched out’, she does not question anything, rather she exudes contempt and hostility towards persons who feel quite satisfied being heterosexual and might even consider the normativity of the binary gender system an important pillar of societies well-being. How would such an attitude contribute to mutual understanding and mutual respect?

LikeLike