Written by

Taiwan garnered international attention in May 2017 when the Constitutional Court declared that it was unconstitutional for the Civil Code to limit marriage to heterosexual couples. In the same ruling, the Court then imposed a two-year deadline for the Legislative Yuan to amend the Civil Code. Despite expectations that Taiwan would be the first country in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage, remarkably little progress has been made.

Meanwhile, organized opposition, largely absent in Taiwan a few years ago, produced considerable backlash to legalization and LGBT rights more broadly. Proposed referendumsrelated to same-sex marriage and LGBT rights cleared the Central Election Commission in April, emboldening conservative organizations. Coordinated disinformation campaigns with foreign assistance from American anti-LGBT groups (also see here) claimed that legalization would result in the spread of AIDS and bestiality, the recruitment of children to become gay, and the broader decline of social norms and morality. One viral campaign claimed that foreign gay men with AIDS would marry locals in order to take advantage of Taiwan’s national health care system. The culmination of these efforts was evident in Taiwan’s elections in November, where clear majorities in five referendums opposed same-sex marriage and other LGBT rights.

This begs a major question: what explains the perceived rapid shift in Taiwanese public perceptions on same-sex marriage?

Unlike in the U.S., the issue of same-sex marriage did not appear politically salient in Taiwan until, it seems, after the Constitutional Court decision. Numerous surveys prior to the decision suggested that a slight majority of Taiwanese supported legalization, including surveys from political parties (e.g. the KMT), LGBT organizations, and both Taiwan Social Change Surveys in 2012 and 2015. Taiwanese public opinion appeared to mirror the acceptance of the LGBT community seen in the Americas and Europe in years prior to legalization.

Furthermore, Taiwan already annually hosts the largest pride parade in Asia. This year, the parade set records for attendance, and another massive pro-LGBT rally took place outside the Presidential Office just weeks before the election in November.

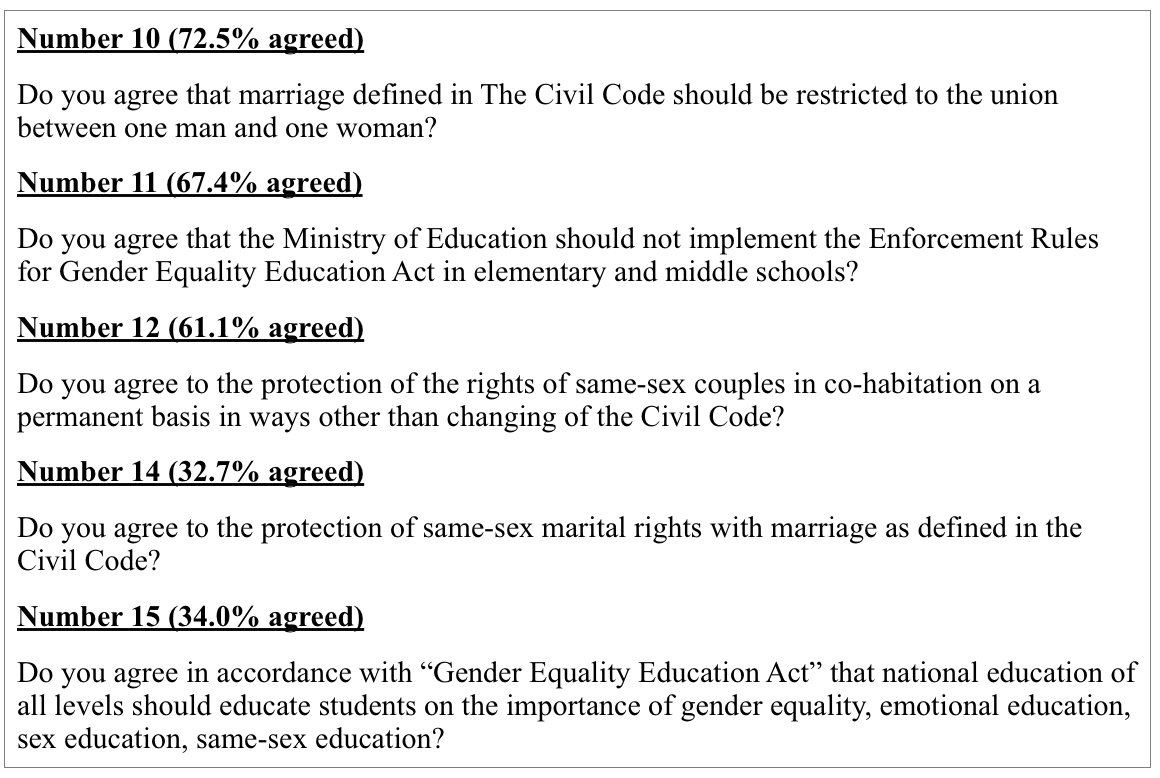

Yet, for four of the five relevant referendums, opponents of same-sex marriage could declare clear-cut victories. On the fifth, Referendum Question No. 12, one could selectively interpret the results favorably for some form of legal protection while most would likely identify the results as reaffirming opposition to same-sex marriage. Furthermore, despite the Judicial Yuan’s declaration that any law that follows from these referendums cannot contradict the Constitutional Court interpretation, the results of the referendums will likely encourage the Tsai Ing-wen administration and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to further shy away from promises made in the lead-up to the 2016 elections as they head towards the 2020 general elections.

We contend that despite signs of LGBT support in Taiwan, many — both in Taiwan and abroad — ignored the number of Taiwanese with no set opinion on same-sex marriage and LGBT rights and overlooked the role that issue-framing plays. In particular, we suspect that views on same-sex marriage for many Taiwanese remained conditional on how the issue is presented in the media. This is consistent with the broader literature in social science on issue-framing.

To address the role of framing on support for legalization, we conducted an experimental survey on March 29-30, 2018, through PollcracyLab. Six hundred respondents were asked their position on legalization on a five-point scale, from strongly opposed to strongly support after reading one of five randomized prompts:

Version 1(V1): Taiwan’s Constitutional Court in 2017 ordered the Legislative Yuan to amend the law to allow for same-sex marriage.

Version 2(V2): Taiwan’s Constitutional Court in 2017 ordered the Legislative Yuan to amend the law to allow for same-sex marriage. Proponents claim legalization would be a sign of Taiwan’s progressiveness.

Version 3(V3): Taiwan’s Constitutional Court in 2017 ordered the Legislative Yuan to amend the law to allow for same-sex marriage. Opponents fear that it will negatively affect the traditional family structure.

Version 4(V4): Taiwan’s Constitutional Court in 2017 ordered the Legislative Yuan to amend the law to allow for same-sex marriage. Proponents claim would be a sign of Taiwan’s progressiveness, but opponents fear that it will affect the traditional family structure.

In the total sample, support remained tepid, with 33.67 percent opposed or strongly opposed, and 39 percent supportive or strongly supportive. However, the survey showed small declines in support among those who received the prompts that included opponents’ claims about legalization undermining traditional family structures. Limited to respondents identifying with the two largest parties (the KMT and DPP) (see below), the results are striking. Support among KMT identifiers declines by about 10 points regardless of additional information. More troubling, perhaps, was that support among DPP identifiers declined by over 18 points when opponents’ claims about undermining traditional families were mentioned. In addition, additional analysis suggested that a sizable section of the population could be swayed by evoking traditional values arguments, even after controlling for basic demographic and partisan factors. As traditional values comprised the primary argument of many anti-LGBT groups in Taiwan, it should come as no surprise that these arguments were effective in their efforts.

The results here give insight into what originally would seem to be contradictory evidence — support for legalization before the Constitutional Court decision and growing opposition afterwards — by suggesting that how legalization is presented matters. The results also suggest that supporters, especially within the DPP, may have under-appreciated the extent to which the issue of same-sex marriage remained contentious within the party, especially because many Taiwanese who voiced ambivalence or had no opinion on legalization were still open to appeals.

Furthermore, the results suggest the extent to which appeals framing an issue in terms of potential risks and losses resonate more strongly than positive frames. This is consistent with the broader literature on prospect theory as well as previous research in Taiwan regarding the impact of free-trade agreements (FTA). In this case, the “loss” in the situation would be the perceived undermining of traditional values emphasized by anti-LGBT groups.

Taiwanese have shown through these referendums that this support does not necessarily translate into a rejection of the “undermining of traditional family structures” claims as is stereotyped to occur with support of marriage between same sex couples.

While pro-LGBT groups and DPP officials talked about Taiwan’s growing progressiveness and efforts at equality, they may have misidentified the emotional appeals associated with the traditional values arguments while not consistently providing a counter-frame with the same emotional resonance. Additionally, it is possible that the uncertainty of the implementation of same-sex marriage legalization made it less favorable, with Taiwanese with no strong opinion defaulting to the current status quo rather than move into uncharted waters.

Another major takeaway from this discovery is the importance of clearly defining rights within the LGBT community. One cannot equate support for LGBT rights as support for same-sex marriage. While same-sex household registration expanded across much of Taiwan through local ordinances (also see here about public housing), and Taiwan is revered as a top LGBT travel destination, Taiwanese have shown through these referendums that this support does not necessarily translate into a rejection of the “undermining of traditional family structures” claims as is stereotyped to occur with support of marriage between same sex couples. In this way, it is also important to regard the fight for LGBT rights in Taiwan as unique when compared to other countries, especially those in the West. For example, Taiwan, as the first location in Asia to seriously consider the legalization of same-sex marriage, was often compared to countries in Europe and the Americas as other regional examples were unprecedented. Within notable Western examples, especially that of the U.S., rights like marriage have been nationally mandated while some rights, such as housing and fairness ordinances, are decided at the local level and are not uniform even at the state level.

For these reasons, it is of paramount importance to continue to separately define LGBT rights and not simply equate support for the LGBT community with support for same-sex marriage. In future, specifically addressing the association between same sex marriage and the framing of the issue by opponents as undermining traditional family structures, perhaps with a similarly emotionally salient counter frame, could be a means for the DPP and supporters more broadly to reorient the discussion in their favor.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His main area of research focuses on the electoral politics in East Asian democracies. Isabel Eliassen is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs and Chinese. Andi Dahmer is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University.

The piece was first published by Taiwan Sentinel in December 2018. Taiwan Insight has been authorized to repost this article. Image credit: CC Flickr/ Carrie Kellenberger

First let’s examine some frames in this article.

It says that opposition “to legalization and LGBT rights more broadly” is “organized”. (This statement by itself is innocuous enough. It does not imply that opposing the grant of specific rights is illegitimate. However, the opposition got organized recently. Perhaps, one should be a bit wary.)

And it says that “coordinated disinformation campaigns … claimed that”: [the most ridiculous instances of such claims are inserted here]. (Indeed, the opposition is sinister. Their claims are malicious, and since the opposition is organized, all their claims must be malicious by association. We suspected it and it is true: the opposition is illegitimate, all opposition is illegitimate.)

Since the mind of the article’s reader is framed in favour of the authors’ opinion by now, a suggestive question may be effective. And sure, here it follows in the next paragraph of the article.

“This begs a major question: what explains the perceived rapid shift in Taiwanese public perceptions on same-sex marriage?” (Unfortunately, this question is circular. ‘This’, that supposedly begs, is the answer to the question. The explanation, “coordinated disinformation campaigns” by “organized opposition”, has been given in the previous paragraph of the article, albeit in a heavily framed form. However, a distracted reader won’t notice this consciously, rather the frames will be re-enforced in their mind.)

Next the reader is further lead astray. From the difference in prior survey results to later referenda results, the authors deduce a shift over time from support to rejection, such again re-enforcing the previously set frames. However, the authors’ deduction is false.

First, any person’s opinion stated in a survey which inherently lacks much consequence may quite well differ from that person’s vote in a referendum which may have real consequences in law. In the first case there may be little in-depth consideration of pros and cons, less so in the second case.

Second, questions in surveys and in referenda are differently worded. A person’s answer to: do you support same-sex marriage? may contradict the answer to: do you agree that marriage defined in The Civil Code should be restricted to the union between one man and one woman?

Third, the questions asked in the referenda are perfectly in line with the Constitutional Court’s ruling. No result would have contradicted the ruling of the court.

Forth, the assertion at the end of the second paragraph in this article that “clear majorities in five referendums opposed same-sex marriage” is patently false because in Referendum Question No. 12 a clear majority agreed to protect the rights of same-sex couples. This false assertion begs the question: Is the quest for same-sex marriage about gaining legal protection for same-sex family life or is it about forcing one’s own extended idea of marriage and family on conservative heterosexual couples? Is this about “declaring clear-cut victories” or about gaining legal recognition?

There is another assertion in the article that appears a bit strange: “Many … overlooked the role that issue-framing plays”. On the one hand the opponents are alleged of framing same-sex marriage as “undermining traditional family structures” and on the other hand there are supporters of same-sex marriage who frame opponents as coordinated disinformation campaigners, as the authors do in this article. Then, who are the many who overlooked the role of issue-framing? Isn’t there issue-framing all over the place? On every side?

As for the “experimental survey on March 29-30, 2018” testing “the role of framing on support for legalization”: Yes, framing matters and indeed, framing an issue as a loss is more effective than framing it as a gain. That’s well established in psychological studies. So, nothing surprising there and faithfully implemented by the authors in this article (see top of this comment).

What is surprising, however, is the willingness of half the population to go against a verdict of Taiwan’s Constitutional Court, and of one sixth of the population to be swayed in their opinion by an unsubstantiated claim of progressiveness, and of one third of the population to be swayed in their opinion by someone else’s claimed fear. Could it be that the participants answered the survey without any mental deliberation, just following the first whiff of an emotion? Could it be that many “Taiwanese had no set opinion on same-sex marriage and LGBT rights”, as suggested in the article? Or could it be that most survey participants simply did not care about same-sex marriage and LGBT rights and, therefore, invested very little energy and thought on the issue?

So, indeed, framing works. However, this is an article in an academic journal. The readers are predominantly academics. Most academics are progressive. So, there is no need to sway their opinion by framing the issue. Academics are supposed to rather engage in sound reasoning while exploring the world and society. Furthermore, it might be even unethical to advise campaigners to utilise “a similarly emotionally salient counter frame” because it prevents well-reasoned decisions the functioning of a democracy depends on. Let’s try sound arguments for a change.

LikeLike

Are sound arguments free of frames? Probably never. So it might be advisable to differentiate between benign framing and insidious, malicious framing.

The first helps the other side to relate to the argument and to access it. The second does distort, defame and degrade. How does one react to bad framing? Using even worse counter frames?

Yes, if one wants to start a war. No, if one aims for an insightful debate. Re-framing might do the job to uncover how insidious and malicious the original frames are.

By the way, bad framing need not be intentional. It is often the consequence of the attitude that we are right and they are wrong, accompanied by the attitude that questioning of our position is an attack on humanity.

And now I need to take some time for self-reflection.

LikeLike

Let me suggest a framework for the evolution of societies.

To survive, societies must adapt to the ever changing social and physical environment. Progressive members of any society drive that adaptation by introducing all kinds of social change. If unchecked, some of those changes might throw a society into chaos. Conservative members of any society resist change. If unchecked, no change might happen, society fossilises and eventually goes under.

Progressive members of societies tend to enthusiastically dismantle old norms and expectations, often ignoring that some of them still serve a useful function. Conservative members of societies tend to hold on to all norms and expectations, often ignoring that some have outlived their usefulness and might even be harmful. The opposite dichotomy holds true for introduced changes.

So it is easy to see that progressives as well as conservatives have valuable roles in the evolution of societies. It is important that none overpowers the other and that both engage in constructive debate, such arriving at a consensual balance of each sides preferences. This way the well-being of any society is served best.

LikeLike