Written by Lin Pei-ying and Isabelle Cockel.

Image credit: Li Yi-chieh, Shih Chou Ching-chiang’s granddaughter Li Yi-chieh and her son delivered by Pei-ying Li.

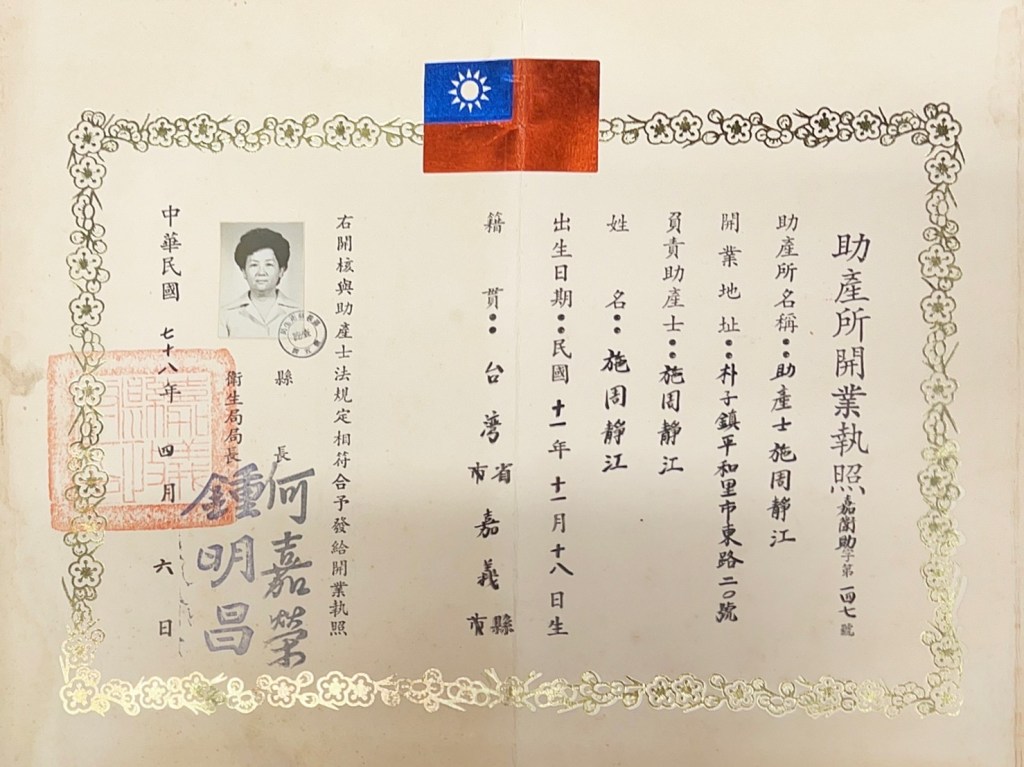

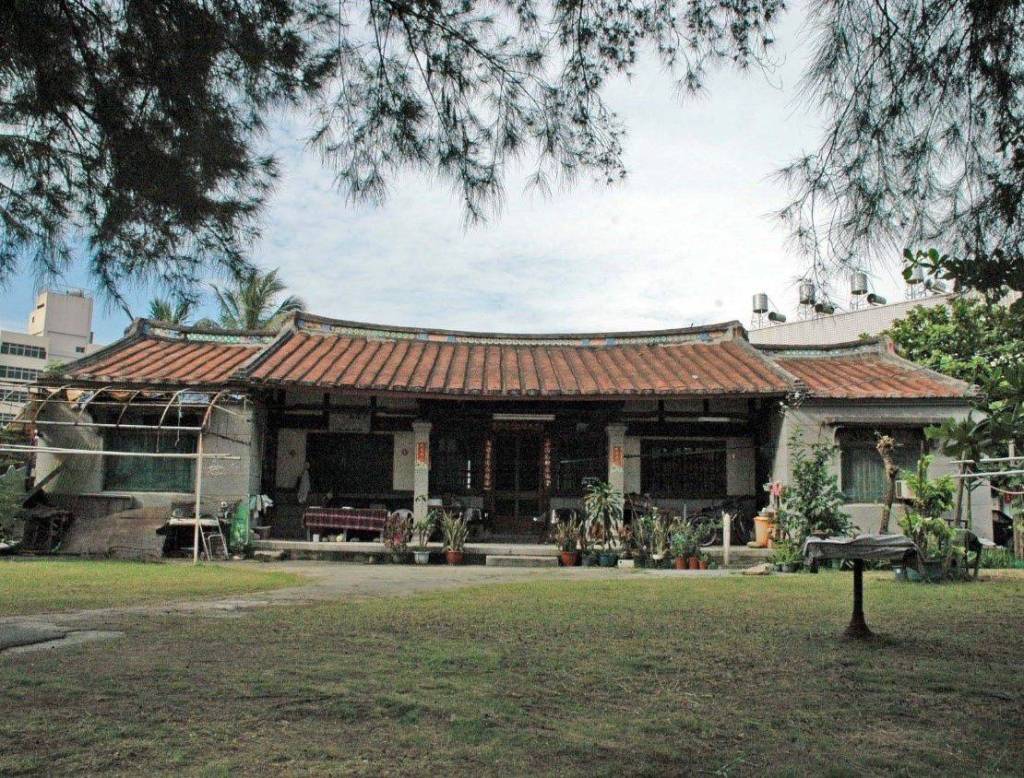

This essay is dedicated to the late Shih Chou Ching-chiang, a forerunner of modern midwifery in Taiwan. Born on 18th November 1922, Shih Chou was first certified by the Japanese colonial government for her medical profession. She was certified again by the provincial Taiwanese government in 1948 and received her license issued by the Chiayi County Government in 1950 to run her midwife practice at the age of 28. Located in Putsu Township, her home was also her practice and the first contact with the world for many people of Putsu who were delivered by her. Greeting nearly 10,000 newborns, Shih Chou passed away at the age of 96, and a public campaign ensued to preserve her century-old home. The campaign failed to save it, and her home was demolished on 2nd May 2022, six months before her 100th birthday.

Midwives are amongst those in the medical system who detect gestational hypertension or diabetes during pregnancy and who deliver newborns to arrive in this world. Their critical role as such is recognised, and their service is commonly used in the UK, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United States, Japan, and China. However, it is a very different story in Taiwan. On average, there are 200,000 births per annum in Taiwan. According to the Taiwan Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology, in 2015, out of a combined number of 2,600 obstetricians and gynaecologists nationwide, only 800 of them actually engaged in the delivery of these 200,000 babies. Their heavy workload is a contrast to that of midwives: From 2004 to 2022, the rate of newborns delivered by midwives was between 0.05 per cent and 0.20 per cent. From a pregnant woman’s point of view, the disadvantages caused by the shortage of obstetricians were compounded by the small number of midwives. If midwives can be re-integrated into the medical system, it will significantly increase the capacity and quality of maternal care. More importantly, reducing medical intervention for women who give birth at the hospital will give them options that are more likely to lead to a kind, personal and autonomous birthing experience that is also conducive to mother-child bonding. It will also give a much-needed push to change the views on pregnancy from being perceived as a disease to being a biological and psychological process.

To this effect, in 2014, in response to the campaign of women’s groups, the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MoHW) launched a ‘Nurse-Midwife Double Care’ (雙師共照) initiative. The ‘double care’ aimed to create a maternal care system where women could choose, according to their preference, amongst ‘friendly, multiple and gentle’ options for their birth plans. Six regional hospitals were selected by the MoHW to facilitate this ‘double care’, and, in that year, a total of 356 women used this newly provided service and delivered it at these hospitals. As a result of this initiative, which reduced unnecessary medical intervention, fewer women were given cesarean section and episiotomy, whilst more women opted for breastfeeding. Receiving a satisfaction rate as high as 99 per cent, this initiative was popular amongst its users. Its popularity notwithstanding, none of these six hospitals remained in this service, citing staffing shortage or overload as the reasons. A much-publicised initiative thus became a one-off trial. Why would high-performing midwifery be sidelined by the medical system?

A contributing factor is the suspension of midwifery education in Taiwan between 1991 and 2001. Before 1991, midwifery education was offered by five-year junior colleges or nursing schools. Their graduates could be licensed to become practitioners after passing the national midwife qualification exam. After 1991, midwifery education was withdrawn until 2001 when Fooyin University (輔英科技大學) and the National Taipei University of Nursing and Health Sciences (台北護理健康大學) brought it back to their curriculum. This return filled the gap. With the execution of the license examination, the provision of midwifery was reinstated, and 90 per cent of them were also licensed as nurses, a dual licensing system that renders them Certified Nurse-Midwifes (CNMs).

Licensing aside, the actual number of midwives available at a maternity theatre is small. As of November 2016, a total of 53,055 professionals are certified as ‘midwifery personnel’. Amongst them, 673 received a higher level of certification. However, out of these 53,055 midwives, only 204 of them registered to practice, and at the end of 2022, only 201 remained in practice. In some counties, such as Miaoli, Keelung, Kinmen, and Lianchiang, there was no midwife at all, whereas in Penghu and Chiayi, there was only a single-digit registration. In addition, as of the end of March 2022, there were only 24 midwifery practices (助產所) operating in Taiwan; in 2024, as shown by the National Health Insurance (NHI) statistics, only 16 of them remain in practice. In 2023, the number of midwives nationwide further slumped to 44, at an average age of 69 years. In a nutshell, midwifery is rapidly disappearing from the medical landscape.

Midwifery scarcity is also attributed to employers’ reluctance to hire licensed midwives. The Standards for Establishing Medical Institutions (醫療機構設置標準) stipulate that hospitals with maternity wards may employ at least one midwife personnel, that such employees may be registered as nurses if they are trained as CNMs and that their on-the-job training may be funded to ensure their quality service. However, requests made by the CNMs for such dual registrations were often turned down by their employing institutions, whilst some local governments were unaware of such registration. For the six regional hospitals who were handpicked to roll out the ‘Nurse-Midwife Double Care’ service, it appeared difficult for them to manage midwifes’ presence. On the one hand, midwives had been absent from the medical system for so long that the knowledge on the part of their employers as to how to utilise the combined services of nurses and midwives became scarce in its own right. These employers were also short of funds to pay for their wages. When being part of the initiative, participating hospitals received grants from the government to pay for their wages. Since the initiative did not roll over to the following year, funding for their wages dried out, and they lost their job.

Midwifery scarcity is further aggravated by other restrictions on their service provision. By law, a midwife can be employed at a hospital as part of the obstetrics department. However, such flexibility is not widely known. According to the Health Promotion Administration (HPA), in 2014, 99.90 per cent of newborns were delivered by doctors, in contrast to a fractional rate of 0.06 per cent delivered by midwives. The contrast changed slightly in 2022 when the former dropped to 99.70 per cent, and the latter rose to 0.2 per cent. These contrasts suggest that, despite the marginal increase, the women who wish to be delivered by midwives remain an extreme minority. This is due to the lack of publicity since most women do not know about the existence of midwives at all, and those who knew relied on word of mouth. They may mistake midwife delivery for home birth, and they may not be able to distinguish the difference between being cared for by a midwife or by a nurse in the obstetrics department. This lack of distinction is owing to the lack of understanding on the part of medical institutions. As pointed out above, medical institutions, as their employers, are mostly unaware of their versatile training and service. If a CNM is lucky enough to be employed by a medical institution, they will most likely work as an ordinary nurse rather than be assigned to the obstetrics department. If they work as a midwifery practitioner at a hospital, they will not receive payments for their services via the National Health Insurance (NHI). In sum, the visibility of institution-based CNMs will be further marginalised.

By law, a midwife may run their own midwife practice to offer a service tailored to personal needs. As a registered operator, they can independently receive payments for their service via NHI. However, the Medical Law (醫療法) does not give a midwife access to the electronic referral system, so they cannot easily refer their clients to medical institutions for further care. They are also deprived of the access to upload records to the national vaccination system (醫療院所預防接種資料查詢系統). Instead, they are required to upload such records of the newborns delivered by them via administrators at health stations (衛生所).

To conclude, the restrictions on the practice of midwifery have seriously impaired women’s rights. Exclusively channelling women to institution-based maternal care exhausts medical institutions’ capacity whilst sidelining options described by MoHW as ‘friendly and gentle’ for women to choose from. Midwives’ stripped authority to refer women to medical institutions and register newborns’ vaccinations means that they cannot timely care for their clients, whose rights to health are also impacted. The limited employment for midwives at medical institutions and the reduced authorities of their practice set them in an unfair environment. In their entirety, these restrictions and unfairness have violated women’s rights protected by the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in terms of their access to medical care and their right to be employed. It is time for the government and the medical professionals to put their act together and make Taiwan a friendlier place for women to give births.

Lin Pei-ying is a Certified Nurse-Midwife and a Permanent Member of the Council of the National Alliance of Taiwan Women’s Associations.

Dr Isabelle Cockel is a Senior Lecturer in East Asian and International Development Studies at the University of Portsmouth. She is currently the Secretary-General of the European Association of Taiwan Studies. This essay is part of her project entitled ‘We want your labour, not your baby: Indonesian migrant workers’ intimacy, childbirths and the receiving state of Taiwan’. Funded by the University of Tubingen, this project is included in the project entitled ‘Intimacy-Mobility-State Nexus in the Context of Democratic and Authoritarian States: A Case Study of China and Taiwan’.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘In the Name of Birth: Technology, Care and Circumstances‘.