Written by Szu-Yu (Suzy) Chen.

Image credit: Behind the barbed wire by Oleg Afonin/ Flickr, license: CC BY 2.0.

On September 20, 2024, Taiwan’s Constitutional Court (TCC) issued Judgment 113-Hsien-Pan-8 (2024) (113-Hsien-Pan-8, also known as the constitutional case of the death penalty), upholding the constitutionality of the death penalty. This article provides an overview of the legal landscape of the death penalty in Taiwan, highlighting 113-Hsien-Pan-8 and its impact. This ruling has sparked strong reactions from both proponents and opponents of the death penalty. While critics expressed deep disappointment that the death penalty was not abolished, supporters viewed the procedural and substantive restrictions placed on its application as a de facto abolition, condemning the TCC for overstepping its authority. 113-Hsien-Pan-8 represents a crucial moment in Taiwan’s death penalty debate, and its influence warrants continued observation.

How Far Had Taiwan Progressed in Abolishing the Death Penalty Before 113-Hsien-Pan-8?

Before the 113-Hsien-Pan-8 decision, the constitutionality of the death penalty had already been addressed in several rulings. From 1985 to 1999, Justices upheld its constitutionality for crimes such as kidnapping for ransom and drug-related offences, emphasizing the need for capital punishment to deter serious crimes and maintain social order.

Later on, Taiwan’s legal approach to the death penalty began to shift following the incorporation of international human rights conventions into domestic law. The passage of the Implementation Act of the Two Covenants in 2009 provides the conventions with domestic legal status. Also, it requires the government to establish a human rights reporting system, under which the death penalty has always been a key issue in periodic reviews. Invited international experts, through concluding observations, consistently urged Taiwan to move toward abolition and impose an official moratorium and to focus on raising awareness of the inhumane nature of the death penalty instead of citing public opinion as a justification for maintaining it.

Propelled by the implementation and review of human rights conventions, the domestic judicial system has gradually imposed stricter requirements, narrowing the scope of the death penalty. In recent years, the Taiwan Supreme Court has ruled that defendants with mental or intellectual disabilities cannot be sentenced to death. This precedent has led the Supreme Court to overturn several lower court rulings that failed to consider defendants’ mental conditions when determining sentences. Additionally, court practices also limit the death penalty to only the most serious crimes, excluding cases where the arson offender acted with indirect intent.

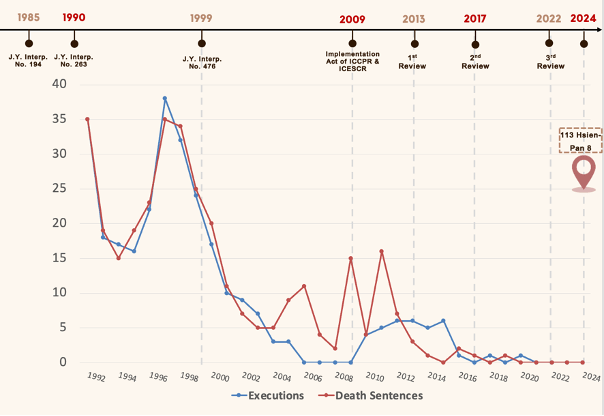

These legal and judicial changes have contributed to a sharp decline in the use of the death penalty in Taiwan. From the 1990s to 2024, the number of death sentences and executions has dropped significantly (Figure 1). This trend has been described as mirroring similar developments in other countries that still retain the death penalty and aligning with the global movement toward abolition, as noted by the International Review Committee in their Review of the Third Reports of the Government of Taiwan on the Implementation of the International Human Rights Covenants. However, the majority of public opinion to date appears to strongly oppose the abolition of the death penalty, viewing it as a necessary regulatory response to serious crimes and a form of reparation for victims.

(Self-produced by the author)

What 113-Hsien-Pan-8 says?

113-Hsien-Pan-8 was brought before the bench by 37 death row inmates. The TCC confirmed the petitions’ admissibility in January 2024 and announced that the preparatory hearing would be held in February 2024, followed by the oral argument hearing on April 23, 2024. In addition to the legal representatives of the death row inmates and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), six expert witnesses, the National Human Rights Commission, and the Association for Victims Support also participated in the oral argument hearing. Meanwhile, the TCC received 17 amicus briefs, including submissions from the Judicial Reform Foundation and the Taipei Bar Association. Through the foregoing procedures, the TCC concluded to maintain the death penalty, limiting to use against the most serious offences of intentional homicide, homicide by forced sexual intercourse, homicide by robbing and homicide by kidnapping, and such death penalty could only be sentenced pursuant to the most stringent procedural restriction.

To begin with, 113-Hsien-Pan-8 opined on the constitutional status of the right to life. The TCC affirmed that the right to life is an inherent right of every individual, not granted by the state nor requiring explicit enumeration in the Constitution. While the TCC recognized the right to life as the fundamental basis of human existence, it held that this right is not absolute and may be restricted under exceptional circumstances, specifically in cases involving the most serious crimes that intentionally deprive others of life. Under this context, the TCC affirms that justice retribution and deterrence of serious crimes infringing the right to life remain significant public interests at present and, therefore, rules to maintain the death penalty.

However, acknowledging that the death penalty is an extreme punishment depriving a defendant of their life and the miscarriage of which is irreversible, the TCC announced to use death penalty with caution and restraint, which should be strictly confined to the most serious offences and imposed only through criminal proceedings that fully comply with the most stringent due process requirements. The factors used to determine whether a crime qualifies as the most serious offence include the criminal motive and purpose (e.g., premeditation or malicious intent), criminal methods and degree of participation (e.g., use of deadly weapons or inhumane methods, and the involvement of co-perpetrators), and the criminal outcome (e.g., multiple victims, targeting vulnerable individuals, or the commission of the crime alongside other serious offences). The most stringent due process requirements are outlined in two key aspects: (1) restrictions on criminal proceedings, such as mandatory legal representation, mandatory oral arguments in final appeals, and a unanimous verdict for death sentences, and (2) ensuring that the death penalty is not imposed on defendants with mental disorders or intellectual disabilities that impair their judgment, trial competency, or competence for execution. Under this context, in addition to upholding the constitutionality of the death penalty and outlining potential avenues for relief for the 37 death row inmates, 113-Hsien-Pan-8 mandates that the Legislative Yuan amend laws and regulations related to the most stringent due process requirements within two years.

While 113-Hsien-Pan-8 appears to disadvantageously end the previous era of efforts to abolish the death penalty, it nonetheless offers some grounds for future advocacy. For instance, the TCC suggested that competent authorities study appropriate alternative punishments replacing the death penalty. Additionally, the TCC acknowledged that the average level of education among the petitioning death row inmates is significantly lower than that of the general population in Taiwan, raising concerns about whether the imposition of the death penalty disproportionately affects individuals from socioeconomically and educationally disadvantaged backgrounds, thereby resulting in an unfavourable disparity in sentencing outcomes. Furthermore, the TCC emphasized that any execution failing to comply with due process or infringing upon human dignity would constitute cruel and inhumane punishment prohibited by the Constitution, implicitly highlighting long-standing criticisms of improper execution procedures in practice.

What has happened after 113-Hsien-Pan 8?

Upon the release of the decision, the TCC faced severe criticism from both proponents and opponents of the death penalty. While opponents expressed deep disappointment at the TCC’s decision not to abolish the death penalty, supporters viewed the procedural and substantive restrictions placed on its application as a de facto abolition, strongly condemning the TCC for overstepping its authority. These expressions of discontent quickly escalated into significant political pressure, prompting the Legislative Yuan to reject judicial nominees who supported the abolition of the death penalty and to amend the Constitutional Court Procedure Act to raise the statutory threshold for constitutional rulings. Furthermore, the KMT Chairperson has announced to launch of a campaign to hold a referendum against the abolition of the death penalty, countering the recall motions against the KMT legislators.

Meanwhile, the Taiwan Supreme Court rendered a decision rejecting the prosecutor’s appeal for a death sentence. The Court applied the criteria for the most serious crimes, determining that the offence in question was an occasional crime rather than a premeditated murder. It also acknowledged the possibility of the defendant’s rehabilitation, provided they remain in an environment with sufficient protective factors. Citing 113-Hsien-Pan-8, the Taiwan Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision of a life sentence. On the other hand, on March 10, 2025, the Taiwan Kaohsiung District Court ruled the first death sentence after case 113-Hsien-Pan-8.

The most recent development from the executive branch is the execution of Lin-Kai Huang on January 16, 2025. The MOJ announced its decision to carry out the execution, stating that the offence met the criteria outlined in 113-Hsien-Pan-8. Following the announcement, the execution was carried out within hours on the same day, despite pending requests for a retrial and an extraordinary appeal. Moreover, the competent authorities had yet to begin the preparatory work necessary to amend laws and regulations governing the procedural and substantive evaluation of death row inmates’ competence for execution. This execution marks the end of Taiwan’s zero-execution practice since 2020. It offers a definitive response to the ongoing debate over whether 113-Hsien-Pan-8 has effectively established a de facto moratorium on executions.

Looking back at the history leading up to 113-Hsien-Pan-8 and examining the current reactions from the legislative, judicial, and executive branches, it seems that Taiwan is entering a new era in its approach to the death penalty. 113-Hsien-Pan-8 stands as a landmark ruling in Taiwan’s death penalty debate, and its influence merits continued observation.

Szu-Yu (Suzy) Chen (suzy.s.y.chen@gmail.com) is a practising attorney in Taiwan specializing in constitutional and administrative litigation. She serves as a member of the Executive Committee of the Judicial Reform Foundation and the Human Rights Committees of both the Taipei Bar Association and the Taiwan Bar Association. She holds an LL.M. from Harvard Law School.