Written by Nancy Guy

Image credit: Provided by the author. Neighbours, with their pre-sorted trash, meet the garbage brigade in Taipei City’s Da An District. 22 October 2022.

In the opening scene of pop singer Yoga Lin’s music video “Garbage Baby” (垃圾寶貝) (2023), a yellow toy garbage truck rolls between bags of garbage to the tune of Taiwan’s iconic garbage truck melody “Maiden’s Prayer” (少女的祈禱). In this touchingly beautiful song, garbage is a metaphor for the personal shortcomings and challenges that must be tolerated, and even embraced, in committed relationships. Lin’s key message is “to let everyone know that everyone is a beloved baby, and your flaws are adorable”. The last line, which Lin speaks rather than sings, is “You are a baby, not garbage”.

Garbage, or rather, thoughts of garbage, are part of daily life in Taiwan. This is illustrated in the practices of individuals and households as they manage the material byproducts of everyday living. It is also reflected in all manner of creative practices. Lin’s “Garbage Baby” is just one of many popular songs to reference garbage. What appears to be the first piece by a major artist to raise this sometimes stinking subject is Luo Dayou’s 1983 song “Super Citizens” (超級市民). Since then, more than one hundred pop songs have mentioned garbage in their lyrics, including Sandee Chan’s “Forgotten” (忽略) (1997) and Kou Chou Ching and Alilis’s “Grey Coastlines” (灰色海岸線) (2009). Lyric references may range from a single mention of garbage in a love song to a central theme in an environmentalist piece. Some song melodies, such as Shih Wen-bin’s “Home Sweet Home” (我的家) (2000) and Mayday’s “Garbage Truck” (垃圾車) (2004), are even built around the best-known garbage truck melodies.

Themes involving garbage and its disposal also appear in films, such as Tsai Ming-liang’s The River (河流 (1997), Ruan Fengyi’s multiple award-winning American Girl (美國女孩) (2001), Reclaim (一家之主) directed by Wang Xijie (2022), and in television shows, including the Netflix series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!) (2022) written and directed by Chen Wei-ling. Garbage as a metaphor for things, including emotional attachments one should purge, made its way onto the stage in the hit musical Taking out the Garbage (倒垃圾) directed by Hsieh Nien-tsu, which ran multiple times and had revivals between 2020 and 2024.

All of the daily practices surrounding waste management have deeply impacted ways of knowing and being in Taiwan. That a uniquely Taiwanese “garbage consciousness” has formed is partly illustrated by the frequency with which references to garbage, whether as actual trash or as a metaphor for human feelings and emotions, appear in songs and other forms of creative expression.

Several key elements combine to keep garbage on the minds of Taiwanese citizens. First, Taiwan’s humid, subtropical climate is hospitable to rats, ants, and cockroaches; purging food waste from one’s home is a frequent concern lest it attract pests. Second, high-density housing in urban centres does not allow residents to store trash outside their living spaces (as is common in Europe and the United States, for example, where residents place garbage in bins in their garages or alleyways where they await weekly pickup). Simply put, there is no space safe from pest intrusion. These factors combine to make municipal waste collection a pressing, almost daily event. In Taipei, for example, garbage brigades move through the city five nights a week picking up citizens’ trash, compostables, and recyclables. Third, the limitation of space extends beyond that of individual dwellings. The island itself is short of room for landfills. To address waste accumulation, municipal governments have developed effective schemes to reduce unrecyclable waste. As a result, Taiwan has one of the best recycling rates in the world. Nevertheless, waste is still a seemingly intractable problem. Last, but not least, is that garbage trucks broadcast music to signal their arrival at trash collection pickup spots. Arguably, there is no more pervasive music in Taiwan than that of the regular broadcast of garbage trucks as they wind their way through urban and rural streets, calling residents to dump their household waste. Whether you are heading out to dump your trash or not, the trucks’ music evokes garbage, if only for a moment.

While Taiwan’s musical garbage trucks have garnered a good deal of international attention (a Google or YouTube search garners many hits), how the island’s trucks became musical and how their key melody, the “Maiden’s Prayer”, has perservered for more than 50 years is not widely known.

The establishment of the island’s musical garbage trucks was partly a product of Cold War policies. Taipei City purchased Taiwan’s first musical garbage trucks from Japan in 1967 with the aid of a large loan from the Sino-American Development Fund (中美發展基金計畫). Twenty-one garbage trucks and thirty-nine sewer trucks acquired with these funds were put into service in early 1968. The garbage trucks came with a sound system already installed, and it played one tune: the “Maiden’s Prayer”.

It did not take long for this music to become part of the local soundscape and to be referenced in popular culture. When the musical trucks went into service in 1968, they began their collection routines at 5:30 in the morning. The 1969 Taiwanese-language film Rice Dumpling Vendor (燒肉粽) drew on this already familiar sonic symbol. The delicate sound of the “Maiden’s Prayer” played on a music box is the soundtrack to a scene in which a young girl rubs her eyes, as if she’s just awakened, and calls for her father, who has escaped the family home in the middle of the night.

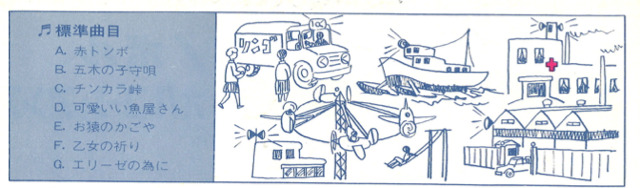

The sound system on the early trucks was devised by the Noboru Electric company situated in Osaka, Japan. Noboru sold their sound systems not only for garbage trucks, but also for mobile sales, sightseeing boats, kindergarten buses, among other uses. Noboru had developed a transistor amplifier to broadcast the sound from a wind-up mechanical music box (such as that heard in the Rice Dumpling Vendor), which they purchased from a music box manufacturer and installed directly inside the amplifier. Each music box could only play one tune. Noboru offered its customers a choice of seven standard songs, one of which was the “Maiden’s Prayer”. According to Noboru’s 1967 product brochure, the standard songs were “Akatonbo” (Red Dragonfly), “Itsuki no Komoriuta” (Itsuki Lullaby), “Chinkara Tōge”, “Kawaii Sakanaya-san” (Cute Fishmonger), “Osaru no Kagoya” (Monkey Palanquin), “Otome no Inori” (Maiden’s Prayer), and “Für Elise” (給愛麗絲). There is no evidence to suggest that officials in Taiwan purposely chose the “Maiden’s Prayer” when they procured the original musical garbage trucks. In fact, this point was raised in a Legislative Yuan Education Committee meeting held in 1968 and mentioned below.

Image credit: Provided by the author with permission of the Noboru Electric Co., Ltd. Image from Noburo’s 1967 product catalogue showing the titles of the seven songs available for installation on their sound system. The “Maiden’s Prayer” is the letter F.

The “Maiden’s Prayer” is a classic piano piece penned by Polish composer Bądarzewska-Baranowska and first published in 1856. It has been the dominant garbage truck melody for nearly six decades. Beethoven’s “Für Elise” also established itself in the garbage truck repertoire, possibly in the mid 1990s, though there is no direct evidence supporting the timing of its inclusion. Within less than a year of the “Maiden’s Prayer”’s adoption, it met with its first challenge. The Economic Daily (經濟日報) reported on 24 November 1968, Legislator Lin Dong (林棟) had complained in an education committee meeting that it was improper for a song representing a pure, young maiden to be associated with garbage. The director of the Cultural Affairs Bureau was instructed to come up with an alternative tune for garbage trucks to broadcast. This, like many attempts to replace “Maiden’s Prayer” over the following decades, led nowhere.

The next attack originating in the halls of government came during a police and sanitation committee meeting in November 1983, when Taipei City Councilman Chen Yirong (陳怡榮) claimed that citizens were finding the repeated playing of “The Maiden’s Prayer” hard to bear. According to a report in the 12 November 1983 United Daily News, Councilman Chen estimated that sanitation workers heard the tune 10,000 times in a single month; average citizens likely heard it multiple times a day. Chen proclaimed, “People are fed up with hearing ‘The Maiden’s Prayer’ every day.”

Government organisations even sponsored competitions for composers to create new songs to replace the iconic tune. For example, the Taiwan Provincial government held a contest in early 1984; the winning tune was installed in more than 1600 garbage trucks across the island. However, an article published on 9 August by the United Daily News, titled “If the Maiden Doesn’t Pray, Citizens Don’t Know to Dump Their Garbage”, announced that there was no choice but to declare the effort a failure. Citizens were accustomed to hearing “The Maiden’s Prayer”, and they often missed the garbage pickup due to their unfamiliarity with the new tune.

In recent years, communities outside of Taipei City have experimented with alternatives to the capital city’s two standard garbage truck tunes. These replacement tunes typically have strong local significance. For instance, in early 2000, trucks in the Guiren District of Tainan County adopted “I’ve Returned Home” (回鄉的我), a song associated with the area’s native son Chen Tan-Sun (陳唐山), who served as Tainan County Magistrate from 1993 to 2001. Chen was exiled in the United States for decades due to his Taiwan independence activities; he only safely returned after the easing of sedition laws in 1992. The rejection of the long-standing, de facto national garbage melody illustrates that garbage truck music sometimes becomes a sounding space where political and ethnic identities are asserted.

Several Indigenous communities have also replaced the mainstream tunes with their own melodies. In 2002, Majia—a predominantly Indigenous township in Pingtung County—began broadcasting tunes from their own musical culture. In 2013, the song “They Look Different” (長得不一樣) by the popular Indigenous band the Beiyuan Mountain Cats (北原山貓) was employed by Ren’ai Township in Nantou County, which is home to a largely Indigenous population comprised of Seediq, Tayal, and Bunun peoples. Quoted in the China Times on 3 August 2013, the village chief Zhang Zixiao (張子孝) said, “although these two songs [the Maiden’s Prayer and Für Elise] are both pleasant, they cannot well represent the special characteristics of Indigenous people. Since there are no laws requiring their use, we decided to employ newly created music in the Indigenous style.”

Over the last nearly sixty years, the musical broadcasts of Taiwan’s garbage trucks have been the objects of both praise and criticism; they have sometimes even been implicated in contestations related to ethnic and/or political identities. That the garbage truck melodies resound in popular music, film, theatre, and other creative practices, alongside metaphors for waste management, evidences the profound degree to which a unique garbage consciousness and its signature melodies have permeated life in Taiwan.

Nancy Guy is a Professor of Music at the University of California, San Diego, where she also serves as the Co-director of the recently established Center for Taiwan Studies. Recently, she was awarded the Chiu-Shan and Rufina Chen Chancellor’s Endowed Chair in Taiwan Studies at UCSD. As a music scholar, her research has focused on the musics of Taiwan and China, the ecocritical study of music, varieties of opera (including European and Chinese forms), and music and state politics. Guy’s first book, Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan (University of Illinois Press, 2005), won the ASCAP Béla Bartók Award for Excellence in Ethnomusicology. Her second book, The Magic of Beverly Sills (University of Illinois Press, 2015), was named a “Highly Recommended Academic Title” by Choice, the review magazine of the Association for College and Research Libraries. Her most recent book is an edited volume, Resounding Taiwan: Musical Reverberations Across a Vibrant Island (Routledge, 2022).

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Sonic Worlds, Acoustic Politics and Hearing in Taiwan.’