Written by Junbin Tan.

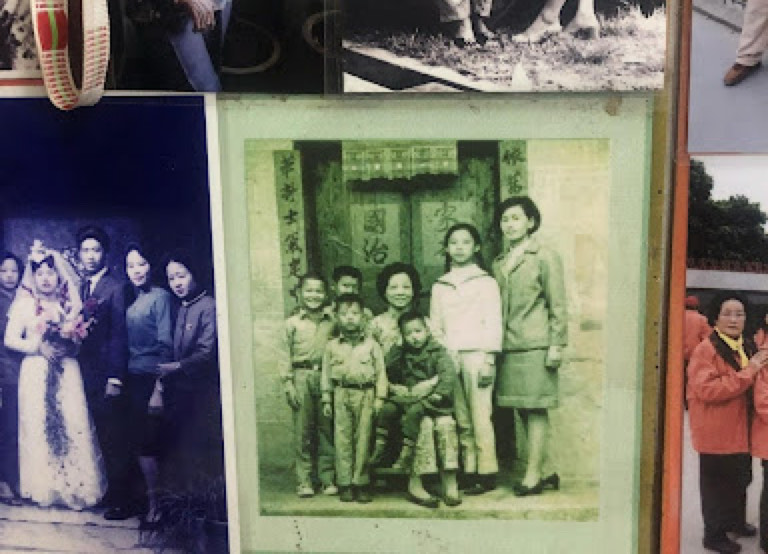

Image credit: Provided by the author. Photo of Grandma Lin with her daughters and four of five sons, taken in the mid-1960s, which the photographer, the late Grandpa Lin carried with him when he moved to Brunei.

“The swallows have returned to build their nest,” Teacher Lin said. We watched the erratic whirls, loops, and swoops of these birds as they darted in and out of their nest, attached to a cornice at his doorsteps. The Lin family’s members, like these swallows, have departed the war and poverty that inflicted Kinmen—Taiwan’s border with and once-battlefront against China—and glided past vast lands and oceans. Some followed their predecessors’ paths to Southeast Asia, and others ventured elsewhere. This article traces the Lin family’s migration trajectories, through which I also narrate the possibilities that Kinmen’s wartime generation created for themselves. In doing so, I show mobility as an adaptive practice—flexible but within limits—that is prompted, warranted, and constrained by political circumstances at the Taiwan Strait and beyond.

From the outside, the Lins’s “traditional” house resembles other homes in Shuangkou village, Kinmen. Two symmetrical rooms flank its main hall. Swallowtail eaves stretch outwards from both sides of its roof, curving elegantly skywards—reflecting, some people say, Kinmen people’s movement outwards and upwards. But the main hall hides a surprise: stepping in, you would first see the god-statues and ancestral tablets that grace the altar, then find yourself captivated, as I was, by over a hundred black-and-white, sepia, and coloured photos that grace the walls. It was through this patchworked archive—in particular, one yellowed photo (see above)—that I learned about the Lins’s migration from Teacher Lin’s 96-year-old mother, Grandma Lin.

Grandma Lin brushed her thumb, now wrinkled with age, over the image of her youthful self. Born in 1931, she was the eldest child of a trader who moved between Kinmen and Xiamen—now the Chinese territory across the border, visible from Kinmen’s shore. She recalled, with the same toothy grin that she had as a girl, her childhood trips to pre-war Xiamen’s busy streets. Commercial activities ended in 1949, and the family’s fortune with it, when the Chinese Civil War created the Republic of China (now ROC, Taiwan) and the People’s Republic, with Kinmen at the border. Another photo on the wall, of Grandma Lin posing in a civilian militia uniform while preparing for “laundry duty” at the camp, allows a glimpse into her wartime adulthood and Kinmen’s militarised transformation into Taiwan’s battlefront with China.

Grandma Lin married Grandpa Lin, twelve years her senior, in the late 1940s. He married at a rather old age of thirty years old because he, like his father and many other men in Kinmen and coastal southern China, had sailed to colonial Southeast Asia—Nanyang, or the Southern Seas as it was known at that time—in search of employment and a better future. His journey was a mixed bag of fortune. Among the men who braved the seas, leaving home to work as manual labourers in Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, many succumbed to poor work conditions, illness, opium addiction, and other causes of death—the Kinmenese saying, “among the ten who left, six died, three resettled, and only one returned” captured this history. Grandpa Lin returned safely, albeit with modest accomplishments. But the skills that he learnt while working at a photo studio in Singapore, however, proved useful when he had to depart Kinmen again in the 1960s.

“This photo was taken shortly before he left us,” Grandma Lin said as she thumbed the yellowed photo. She recalled a time in the late 1960s, over a decade after Grandpa Lin returned and they started a family. A Bruneian Cina Kapitan (the Chinese community’s leader) whose ancestors were from Shuangkou had arrived in Kinmen to recruit workers. Kinmen was the ROC’s battlefront against the PRC in those years. It was impossible for people to leave, but the Kapitan had deep pockets and could smuggle his fellow villagers out. “What could I say? I didn’t want (Grandpa Lin and their eldest, teenage son) to go, but we had many children to feed,” Grandma Lin said, reliving a scene fifty years ago, “Trucks stopped outside our village. I looked on, in fear that I would cry, as they boarded and the trucks drove away.” Grandma Lin’s smile in this photo hides her sorrows, which Grandpa Lin must have also felt when he carried this photo with him.

The family did not separate for long, however. “That man… He’s too honest. He was in Brunei for years but didn’t make any money,” Grandma Lin spoke of her husband, “That’s when I thought, ‘I must go over’. We asked the Kapitan for help and the entire family left in 1967.” An adjacent photo on the wall, of Grandma Lin and her daughter posing smugly beside a taxi (a signifier of modernity in those times), honours the day of their arrival. Not all of Grandma Lin’s children went with her, however. Teacher Lin—the leftmost boy in the photo, who shared Grandma Lin’s broad smile—and his slightly older brother, Tiong, stayed behind because the Lins decided that they should finish high school in Kinmen. Now in Brunei, Grandma Lin put to use the entrepreneurial skills that she learned as a child—recall that she grew up in a merchant family—and started a mom-and-pop shop that gradually grew into a departmental store. The Lins remitted the money they earned back home over the next decade, had their grey-walled house (the photo’s backdrop) torn down with a neighbour’s help and built the spacious one where they now live.

The Lin family’s migration did not end in Brunei. Raised in a migrant culture and with the Lins having more resources, the two youngest boys, Chew and Sheng made their way to Canada and the UK, respectively. Grandma Lin “ran to banks and relatives to borrow money” for the boys’ tuition and boarding fees, which she, an adroit businesswoman by now, paid in instalments over the years using profits from her shop. The boys tightened their belts and worked in eateries in order to make ends meet. These gruelling years paid off when Chew found success in Singapore, where he worked in corporate finance, and Sheng became a world-renowned ophthalmologist.

Faced with Brunei’s unfavourable policies against non-citizens, the Lins closed down their business and returned to Taiwan in the early 1990s, at a time when Kinmen demilitarised and re-entry was easier. But Grandma and Grandpa Lin took flight again. “Grandpa [in his seventies] preferred to stay home,” Grandma Lin said, “but Chew asked if we could move to Singapore to be with his children.” The couple then relocated to Singapore—where Grandpa Lin learned photography, if you recall—where they lived for another decade, when they also visited Sheng’s family in the UK. Only in the early 2000s had they resettled back at Shuangkou where they had left over three decades ago, living in the house that they painstakingly built. It was here that Grandpa Lin spent the last years of his life. Today, his portrait hangs on the wall beside the ancestral altar, overlooking the main hall’s hundreds of photos that now document the Lins’s migration history.

The swallows had returned to nest at the Lins’s doorsteps, as they had the year before, when I visited them at Shuangkou. Grandma Lin treated them with much care: placing a paper box below the nest, watching the birds’ acrobatic flight patterns fondly, and alerting me when they left and the chirps grew silent. “They’ll return next year,” she said assuredly. This article traced parallels between the swallows’ crisscrossing flight paths, on the one hand, and one wartime Kinmen family’s less-than-direct, surprise-filled migration pathways and their eventual return home, on the other. This connection, I think, is not merely metaphorical but also—for the Lins, at least—sustained through their lived experiences: the uncertainties that both motivated and accompanied the move away, the promises and surprises (both bad and good, of family separation and economic opportunities) of mobility, and their return home. The Lins were placed in wartime situations that demanded that they respond quickly, from Grandpa Lin’s decision to hop onto the Kapitan’s truck, to Grandma Lin’s entrepreneurism in starting a shop and sending her children to schools far away, to the Lin’s younger brothers’ ventures to these unfamiliar places.

Then, there is also the social expectation, sometimes internalised as personal desire, for these Kinmen “swallows” who have flown overseas to return home. Return migration appears rather clear when we consider Teacher Lin and his siblings, who have started a family in Taiwan, including those who returned from Brunei in the 1990s. They now fly between their spouses, children, and grandchildren in Taiwan and their aged mother in Kinmen. Official figures show that over 50% of the people registered as Kinmen residents live in Taiwan, although locals claim the actual percentage to be higher. Regardless, these statistics that locate people’s place-of-residence at one fixed site or another do not account for the many people who move frequently. The Lin siblings, for instance, take turns to fly to Kinmen to care for their mother. Teacher Lin, now retired and having more free time, also returns to participate in family ancestral worship and his childhood community’s temple festivals. Adopting a life course perspective, we observe, especially among the people who had left militarised Kinmen as youths in the 1970s-80s, the tendency for back-and-forth migration as they approach later life. If their mobility was born of war and poverty, the flexible strategies of mobility and capital gain that they developed outside Kinmen—with life considerations and kin relations that straddle continents—also paved the way for some of them to return home when home was demilitarised and return became possible.

Junbin Tan is a political anthropologist with broad interests in ageing and generations, ritualised practices, conflict and post-conflict, and political transformations at the Taiwan Strait. He was a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Department of Anthropology, Princeton University and will join the University of Oxford’s Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies as a British Academy International Fellow in 2026. He would like to thank the Lins, especially Grandma Lin and Teacher Lin, for treating him like family and sharing their stories, and Taiwan Insight’s editors for their comments on the initial draft.

This article was published as part of a special issue on Engendering Mobilities: Migration, Memory, and Material Circulations