Written by Eric Scheihagen (徐睿楷)

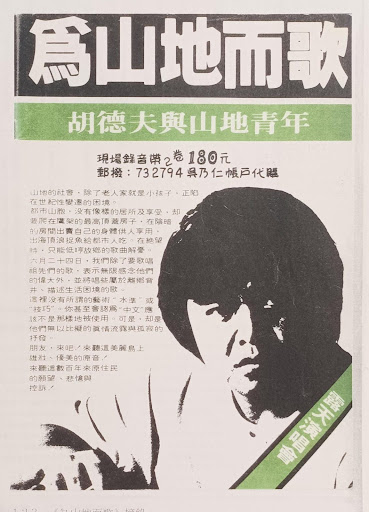

Image credit: Provided by the author. A copy of the poster for the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert featuring Hu Defu.

The 1980s were a time of significant changes in Taiwan. The economy was growing rapidly, and major infrastructure projects were underway across the country. Politically, more and more people were challenging the long-standing authoritarian regime of the Kuomintang. In popular music, new musical trends such as rock reflected the evolving tastes of Taiwanese listeners. Minority ethnic groups such as the Hakka and Taiwanese Indigenous people were becoming more assertive about their cultures and their rights. Many of these changes culminated in a concert of Taiwanese Indigenous music held in Taipei in June 1984, called Singing for the Mountain Lands (為山地而歌).

At that time, Taiwan had been under martial law for 35 years, since the regime of Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi; 蔣介石) and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party; 國民黨) had retreated to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War to the Communists. Chiang Kai-shek’s son Chiang Ching-kuo (Jiang Jingguo; 蔣經國) was now in charge, and facing a growing resistance to authoritarian rule that was reflected in events such as the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident and the Tangwai (Dangwai; 黨外, literally, “outside the party”) Movement. Freedom of speech was still being suppressed, and political opponents of the Kuomintang faced harassment and sometimes imprisonment, but more and more people were willing to challenge the regime.

Taiwan’s popular music was also undergoing a revolution. In the 1970s, the campus folk song movement had emerged, emphasising songs written and performed by younger people. Though these songs generally avoided sensitive political and social topics, in 1982 the singer-songwriter Lo Tayu (Luo Dayou; 羅大佑) released his rock-influenced first album named Pedantry (Zhihuzheye; 之乎者也), which contained socially conscious songs which pushed at the limits set by the government’s song censorship system, as did his 1983 sophomore release. New songs in Hoklo (the language of Taiwan’s majority ethnic group, also known as Minnan or Taiwanese) often outsold Mandarin pop chart hits at Taiwan’s night markets. In 1981, Hakka guitarist and singer Wu Shengzhi (吳盛智) released a Hakka-language album that would inspire a new generation of Hakka singer-songwriters to write songs in their own language.

Taiwan’s Indigenous people had long had their own popular songs, sung in their own languages and in Mandarin (and in previous decades, in Japanese). These songs were passed from settlement to settlement and between different ethnic groups, like folk songs elsewhere in the world, with the lyrics and even the language often varying in other versions. Once in a while, an Indigenous song would cross over to become a hit among the Han majority, with a notable example being “Pitiful Luckless Man” (可憐落魄人), a Mandarin song of Indigenous origin that was the biggest-selling song of 1981 and early 1982 in Taiwan, despite being banned from broadcast on radio or television, as it had not passed through the censorship system.

Though “Pitiful Luckless Man” and many other Indigenous songs of the time had a humorous slant to their lyrics, in truth, Indigenous people in general occupied the lowest ranks of society, suffering from poverty, unemployment and frequent discrimination and prejudice. They disproportionately filled the most complex, most dangerous jobs. A case in point was coal mining, an industry where, at this point, the workers were predominantly Indigenous.

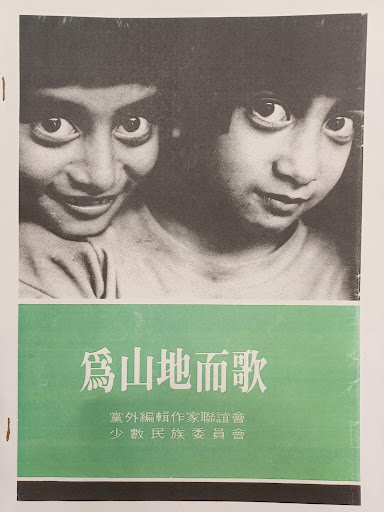

Image credit: Provided by the author. A copy of the songbook for the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert.

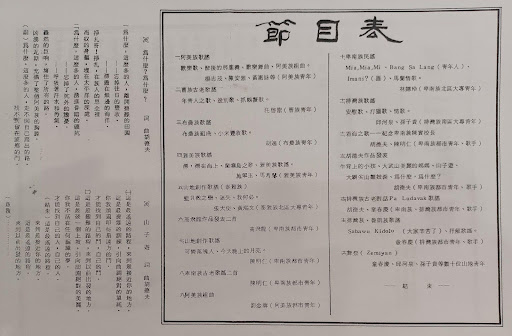

On June 20, 1984, the Haishan Coal Mine Disaster killed 72 miners, the vast majority of whom were Indigenous people from the Amis ethnic group. In response, a group of Taiwanese Indigenous activists and intellectuals organised the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert, held on June 24, 1984, in Taipei to raise funds for the families of the victims of the Haishan incident. They invited singers from all the major Indigenous ethnic groups that had official recognition at the time to perform and interspersed the musical performances with speeches and commentary on the status of Indigenous people in Taiwan, resulting in a concert that both significantly advanced the cause of Indigenous rights and served as a good overview of Taiwanese Indigenous popular music at the time. The most prominent role in the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert was played by Indigenous singer-songwriter Hu Defu (胡德夫), also known as Kimbo Hu. Hu, the son of a Puyuma father and Paiwan mother, had been one of the key early figures in the aforementioned campus folk song movement. He had been one of the first performers to bring Indigenous songs to Taipei audiences of students and intellectuals. In this concert, not only was he a featured performer, but he also served as master of ceremonies, introducing the other performers and speakers and occasionally offering commentary on the situations faced by various Indigenous groups. The concert was closely associated with the Tangwai movement; the songbook was printed by the “Tangwai Editors and Writers Association” (黨外編輯作家聯誼會), and the one political figure invited to speak briefly in the middle of the concert was the Tangwai politician Shih Hsing-chung (Shi Xingzhong; 施性忠), who had just been elected mayor of Hsinchu over ruling party opposition.

Image credit: Provided by the author. Hu Defu and Shih Hsing-chung on stage at the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert.

At that time, Taiwanese Indigenous people in general were referred to as “Mountain People” (山地人) or “Mountain Compatriots” (山胞), though Han Chinese often used more pejorative terms, such as “barbarian”. Nine Indigenous groups were officially recognised by the government (today, sixteen), and all but two of them, the Saisiyat and the Rukai, were represented among the performers. The Paiwan singer Tung Chun-ching (Tong Chunqing; 童春慶) sang a Rukai song to make up for the lack of a Rukai performer. In addition, a woman from the Truku ethnic group, which at the time was still not officially recognised as a separate group, was a last-minute addition to the line-up.

When Hu introduced the performer from the Tsou ethnic group (then referred to as the Tsao), he raised their objections to the then-pervasive legend of Wu Feng (吳鳳), a Han Chinese merchant who had supposedly “civilised” the Tsou by getting them to give up head-hunting. The legend appeared in school textbooks, and the township where the Tsou lived, now known as Alishan Township, was then known as “Wufeng Township”. Hu emphasised that they hoped this legend could be erased from textbooks, which happened after the end of martial law.

In introducing the two performers from the Tao ethnic group (then known as the Yami) of Orchid Island (Lanyu), Hu brought up the issue of nuclear waste, as in 1982, the Taiwan Power Company had set up a nuclear waste storage facility on the island, bringing waste from the main island of Taiwan to be stored there. Subsequently, after decades of protest, in 2019, the government agreed to pay the Tao compensation for setting up the facility without their consent. Tung Chun-ching, who now usually goes by his Paiwan name Djanav Zengror, said that when he was young, he hated the fact that he was a “Mountain Person” because their textbooks said he was descended from savages. Still, when he grew up, he realised that hundreds of years earlier, they had been the masters of the land, and Indigenous identity was something to be proud of.

Image credit: Provided by the author. A copy of the original programme for the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert.

One of the performers was the Puyuma singer Chen Mingren (陳明仁), who, a few years earlier, had popularised the song “Pitiful Luckless Man”. He didn’t originally intend to perform the song at this concert, as he considered it inappropriate. But as he related recently, Hu Defu convinced him otherwise, pointing out that the song’s lyrics (“You can toy with me, you can use me…whenever I see you, you give me a sideways look and stare at me”) could also be interpreted as talking about mainstream Han Chinese society’s (or the government’s) attitude toward Indigenous people. As for Hu himself, in addition to performing several of his folk songs, he debuted two new songs. One was called “The Journey of a Mountain Child” (山子遊; later re-titled “The Longest Road” [最最遙遠的路]); with lyrics adapted from the writings of the Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore, it could be viewed as referring both to the long history of Taiwanese Indigenous people and to the long journey ahead to attain their rightful place in society. The other song, “Why” (為什麼), was directly about the Haishan Coal Mine Disaster, lamenting the deaths of the Amis miners. Hu broke down while performing it, declaring, “Maybe we ‘High Mountain People’ haven’t suffered enough yet. I can promise everybody one thing – after today, I won’t shed any more tears.” Despite this emotional moment, the concert deliberately ended on an upbeat note, with various performers leading the crowd in a medley of songs popular in Taiwan’s Indigenous communities.

Late in 1984, about half a year after this concert, which in many ways was as much about Indigenous consciousness as it was about raising money for a specific cause, Hu Defu, Tung Chun-ching, and others organised The Taiwan Association for Promotion of Indigenous Rights (台灣原住民族權利促進會), with Hu as the group’s first chairman. Among other things, a major goal of the group was to get the government to change the official term from “Mountain People” to “Indigenous People” (原住民族), a goal that was finally achieved on August 1, 1994. The first day of August has since been recognised as “Indigenous People’s Day”, representing the substantial progress in the status of Indigenous people in Taiwan, even if there is still much room for improvement. As Hu Defu’s song says, it has indeed been a long road, and a significant milestone on that road was the Singing for the Mountain Lands concert of 1984.

Eric Scheihagen (徐睿楷) was born and raised in the United States but has lived in Taiwan for more than three decades. He has collected and researched Taiwanese popular music history for most of his time in Taiwan, amassing an extensive collection of CDs, tapes, and vinyl records spanning half a century of Mandarin, Hoklo, Hakka, and Indigenous popular music. One of his main focuses is the popular music of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples. He has published several articles on popular music in English and Chinese, written and translated liner notes for several CDs and contributed to several record exhibitions. He has co-hosted or hosted several radio programmes on Taiwanese popular music, receiving nominations for the “Non-Popular Music Radio Program Award” and the “Non-pop Music Show Host Award” at the 53rd Golden Bell Awards and a nomination for “Genre Music Radio Program” at the 55th Golden Bell Awards.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Sonic Worlds, Acoustic Politics and Hearing in Taiwan.’