Written by Meiyuan Kou

Image credit: Photos taken by the author during her visit to Fuji Temple on August 20, 2023.

The man on the left is Mr Pan Xiantong (潘賢統先生), the caretaker of the Kinmen Association, responsible for maintaining the incense offerings and overseeing the temple.

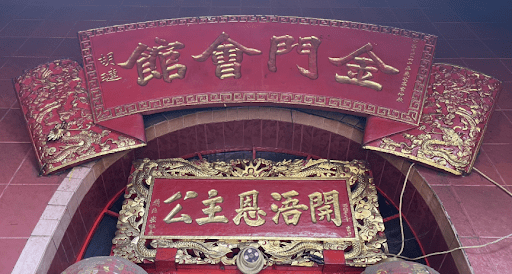

In Saigon – Cholon (now Ho Chi Minh City), among dozens of long-established Chinese community associations, stands a small temple with special diplomatic significance: the Kinmen Association (金門會館), also known as Fuji Temple (孚濟廟). It was not only a place for the Kinmen-origin community in Saigon-Cholon to maintain ties with their distant homeland but also a symbol of the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s “soft diplomacy” in Vietnam. With the support of the Republic of China (Taiwan) government and the approval of the South Vietnam authorities, the temple was established as a non-official yet meaningful channel of people-to-people diplomacy. Although it was not an official diplomatic institution, it functioned as a civil organisation (民間機構) that connected Kinmen people in Vietnam with those in Taiwan through various economic, cultural, and religious exchanges. This informal network reflected both the mutual support among overseas Kinmen communities and the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s efforts to sustain cultural and emotional bonds beyond formal political boundaries.

The Kinmen Association (Fuji Temple), founded in the early 1970s, was the only organisation of Kinmen-origin people in Vietnam. In fact, it also stood as one of the very few—if not the only—Taiwan-related community institutions in the country at that time. Unlike other Chinese groups who had long-established temples and associations, neither the Taiwanese nor the Kinmen people had any formal cultural or religious institutions in Vietnam. Therefore, the founding of the Fuji Temple carried a special symbolic meaning: it served not only as a spiritual home for the Kinmen-origin community but also as an early emblem of Taiwan’s presence and soft diplomacy in South Vietnam before 1975.

Kinmen is a small island located near Xiamen (Mainland China), now under the administration of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Due to infertile land and difficult living conditions, the people of Kinmen have long had a tradition of migrating abroad, especially to Southeast Asia. From the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, many Kinmen residents moved to Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and other countries to make a living. In each location, they often established associations or temples to maintain community connections, organise religious activities and traditional festivals and provide mutual economic support. Compared to other countries in the region, fewer Kinmen people settled in Vietnam. However, their presence in Saigon-Cholon – the area with the largest Chinese population in the country – still left a remarkable mark, especially in religious life and small-scale community activities.

What distinguishes the Kinmen Association in Vietnam from similar associations elsewhere in Southeast Asia is its direct involvement. In 1970, with the support of General Hulian (胡璉將軍) – then Ambassador of the Republic of China to South Vietnam – the Kinmen community in Saigon brought the statue of the deity Muma Hou Chenyuan (Marquis of Horse Herding – 牧馬侯陳淵, also known as En Chu Kong -恩主公) from Kinmen Island for worship. The temple’s plaque was also personally inscribed by General Hulian (see below).

The Fuji Temple was built not only as a religious centre but also as a symbol of community cohesion, reflecting the care of the Republic of China (Taiwan) government for overseas compatriots. This can be seen as a form of “soft diplomacy”, utilising religion and community to maintain Taiwan’s influence in Southeast Asia during the Cold War era.

Beyond its diplomatic role, the association served as a cultural and social hub for the Kinmen community. Although the number of members was small, Fuji Temple still organised traditional festivals, such as the birthday of the deity Muma Hou Chenyuan and his wife, Lunar New Year celebrations, and other important occasions. These festivals not only helped preserve the original cultural traditions but also created spaces for interaction and connection among community members. They maintained ties between the Kinmen community in Vietnam and their homeland, as well as other Kinmen Associations in Southeast Asia. The commemorative flags represent these cherished connections (see below).

However, the history of this association also reflects Vietnam’s political changes. Before 1975, there were approximately 2,000 people of Kinmen origin in Saigon-Cholon. In 1975, the Communist government from the North attacked Saigon, overthrew the Republic of Vietnam in the South, and thus ended the Vietnam War. Following these events, the new government implemented policies restricting the activities of the Chinese community, including those of Kinmen origin. The Kinmen Association fell into stagnation, many members emigrated abroad, and the number of Kinmen people in Vietnam sharply declined to only a few hundred. The temple even had to close for a period.

It was only after the Reform and Opening-up Policy (Doi Moi, 改革開放) in 1986, when policies toward the Chinese gradually relaxed, that the Kinmen Association resumed its activities. As Mr Pan Xiantong (潘賢統先生) – the temple’s caretaker responsible for maintaining the incense offerings and daily upkeep – told me during my field interview on August 20, 2023: “The temple began operating again after Doi Moi, but it was no longer as lively as before. The government’s supervision also became stricter, and discussions about politics were no longer allowed. Nowadays, the temple mainly functions as a place of worship, and members of the association no longer gather as often as they once did – a change that I find inevitable but unfortunate.”

Today, Fuji Temple is not only a place of worship for the Kinmen-origin community but also a cultural link connecting Vietnam, Taiwan, and mainland China. For the remaining Kinmen people in Vietnam, this association serves as a vital landmark for preserving their identity and collective memory in a rapidly changing urban environment.

The Kinmen Association also played a role in maintaining connections with Kinmen Island. Before 1975, many members contributed financially to education, school construction, and assistance for disadvantaged people in Kinmen. This demonstrates the transnational links between the overseas community and their homeland, showing that the association’s role extended beyond religion to social and charitable functions. The organisational structure of the association was also established in the first year of the temple’s inauguration (1974) (see below).

The case of the Kinmen Association highlights the special role of Chinese associations in Southeast Asia. They were not merely places of worship but also had social, economic, and even political functions. With support from the Republic of China (Taiwan) government before 1975, the Kinmen Association in Saigon became a rare example of how a nation could mobilise a migrant community network as a tool of soft diplomacy. Its existence raises broader questions about the relationship between the state, diaspora communities, and transnational cultural identity.

Decades later, this transnational linkage persisted despite the association’s decline in local public vibrancy. For example, in September 2010, Mr Yang Sigong (楊司恭先生), Director of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Ho Chi Minh City, attended the birthday celebration of En Chu Niang (恩主娘), offering donations and extending greetings to local Kinmen-origin residents. More than twenty association members participated, raising around 700 USD as a community fund to assist poorer compatriots and support unemployed members.

Two months later, in November 2010, the Federation of Kinmen Associations in Taiwan convened a meeting titled “Save the Kinmen Association in Vietnam”, urging the Overseas Community Affairs Council and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to assess the deteriorating condition of the Fuji Temple (Kinmen Association) in Ho Chi Minh City. The Kinmen County Government considered dispatching delegates or organising a support mission, while local Taiwanese Kinmen Associations pledged to raise funds and provide assistance.

Together, these examples demonstrate how the Kinmen network continues to operate as a community that transcends borders, sustaining emotional, cultural, and humanitarian connections between Taiwan, Kinmen Island, and the remaining Kinmen descendants in Vietnam and other countries. Through such ongoing transnational efforts, the association maintains a subtle yet enduring role in Taiwan’s soft diplomacy—bridging communities across shifting political boundaries.

Today, as Taiwan continues to promote people-to-people diplomacy and expand its presence in Southeast Asia through the “New Southbound Policy”, historical stories like the Kinmen Association in Vietnam gain renewed significance. They remind us that diplomacy does not only take place through official political channels but can also be sustained through community symbols, religious practices, and cultural heritage. The Kinmen Association thus serves as both a witness to a turbulent period and a gentle yet enduring bridge connecting Vietnam, Taiwan, and Kinmen, reflecting the adaptation, preservation of identity, and cultural continuity of a small but resilient migrant community.

As Ien Ang (2003) observes, “the Chinese diaspora by virtue of its sheer critical mass, global range, and mythical might, has evinced an enormous power to operate as a magnet for anyone who can somehow be identified as ‘Chinese’—no matter how remote the ancestral links.” Although the younger generations of Chinese-Vietnamese may no longer speak the mother languages or follow the same rituals, their association and temples continue to serve as a tangible site of memory, bridging generational and cultural gaps. This significance is further amplified because the Kinmen people themselves are part of the broader Southern Min community (閩南族群)—one of the largest and most influential Chinese groups in Vietnam. In this way, the Kinmen Association not only preserves the heritage of a small migrant community but also exemplifies how community-based institutions can sustain cultural identity, transnational networks, and Taiwan’s soft diplomatic presence across borders.

Meiyuan Kou is a PhD student in Taiwanese Literature (Taiwan and Southeast Asian Studies Program) at National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan.

This article was published as part of a special issue on Engendering Mobilities: Migration, Memory, and Material Circulations.