Written by Chee-Hann Wu.

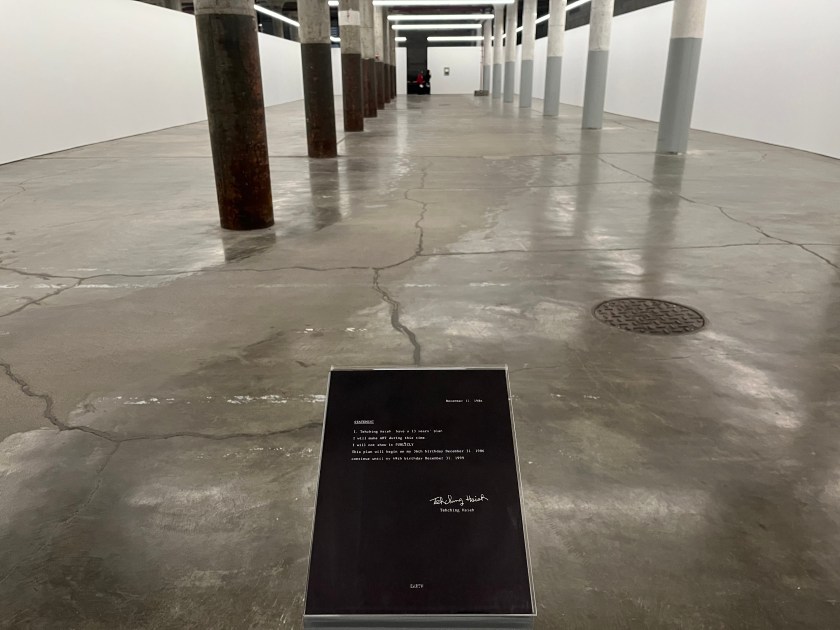

Image credit: “Thirteen Years’ Plan” at Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, taken by the author.

Tehching Hsieh has always used his own body as a calendar—a way of experiencing time and its passing, not through events but through endurance. In the fall of 2025, the exhibition Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999 opened at Dia Beacon, a museum located in the picturesque Hudson Valley, about an hour and a half from New York City by train. The exhibition featured six of the Taiwanese American performance artist’s most influential works and was his first major exhibition in the United States.

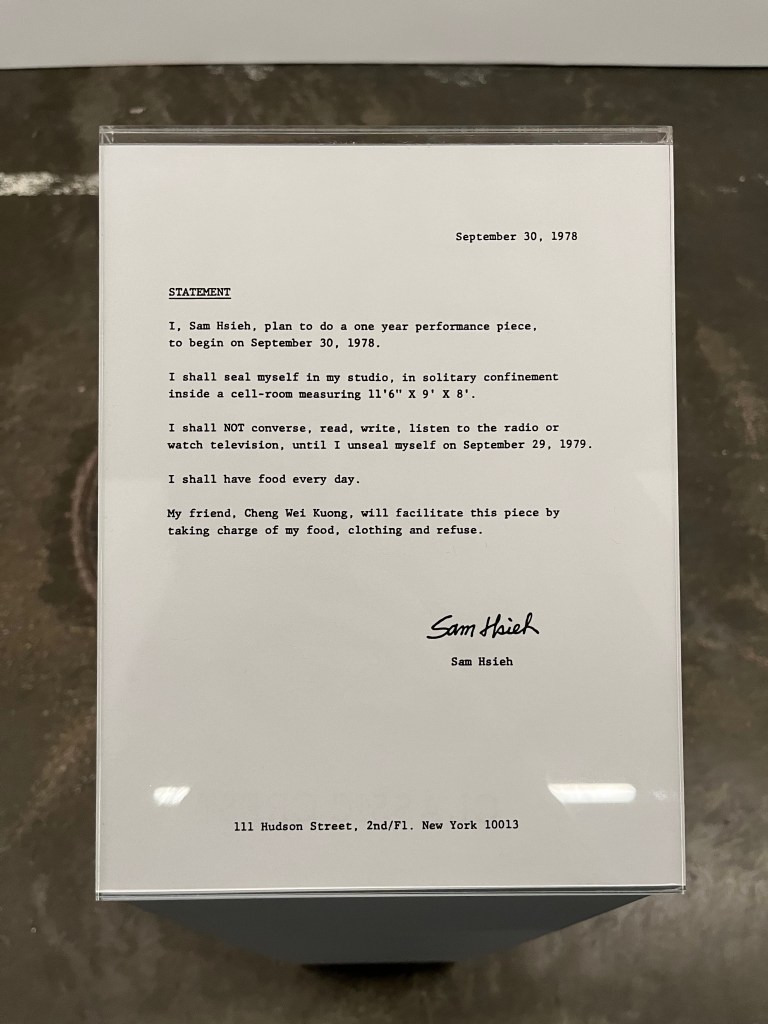

Tehching Hsieh was born in 1950 in Nanzhou, Pingtung County, Taiwan. After finishing his compulsory military service in the early 70s, he had his first solo show at the American News Bureau gallery in Taiwan. Around this time, he began creating a series of works dealing with action and its traces in documents. This series culminated in Jump, in which he recorded his fall from a second-story window, breaking both ankles. Shortly thereafter, Hsieh arrived in the United States, having jumped ship while working as a sailor in 1974. Under the name Sam Hsieh, the artist began his series of five durational pieces, called One Year Performances, in 1978.

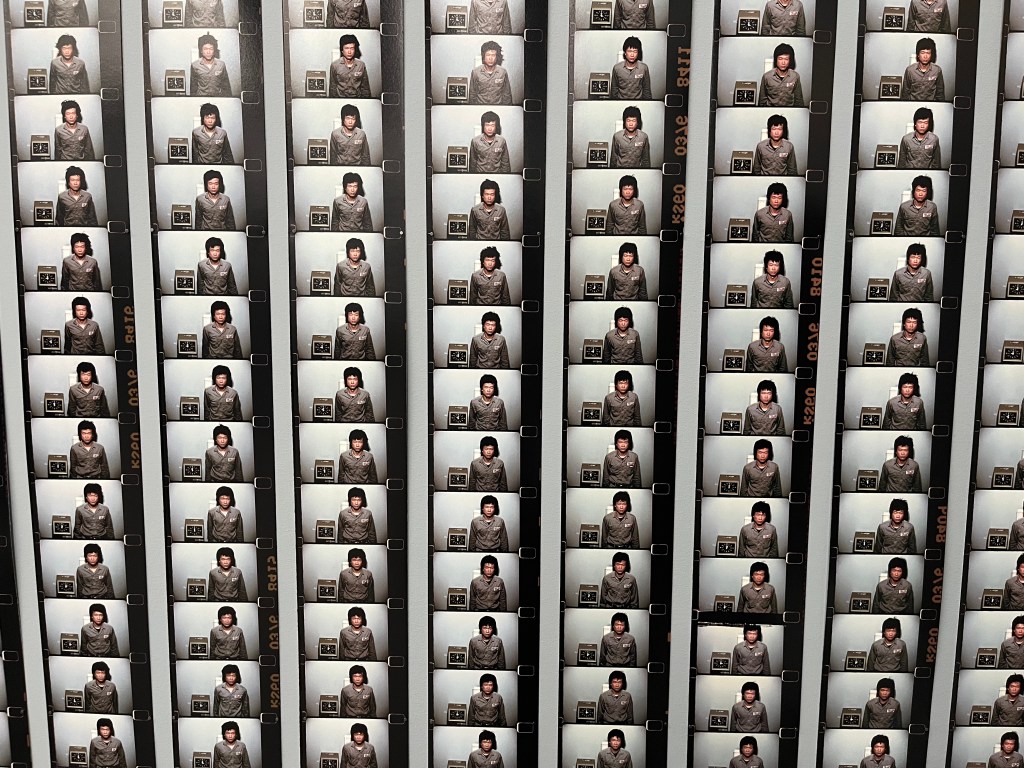

In his “Cage Piece” (1978–79), he confined himself to a wooden cage for a year. In the “Time Clock Piece” (1980–81), he punched a time clock in his studio every hour. Each time he punched the clock, he took a picture of himself. Together, the pictures made up a six-minute film. In the “Outdoor Piece” (1981–82), Hsieh spent a year strolling through the streets of Manhattan, experiencing four seasons. In the “Rope Piece” (1983–84), Hsieh and the artist Linda Montano were tied together with an eight-foot rope. They were not allowed to touch each other for a year. Finally, in 1985–86, Hsieh abstained from all art activities—“not doing art, not talking art, not reading art, not going to art gallery and art museum.”

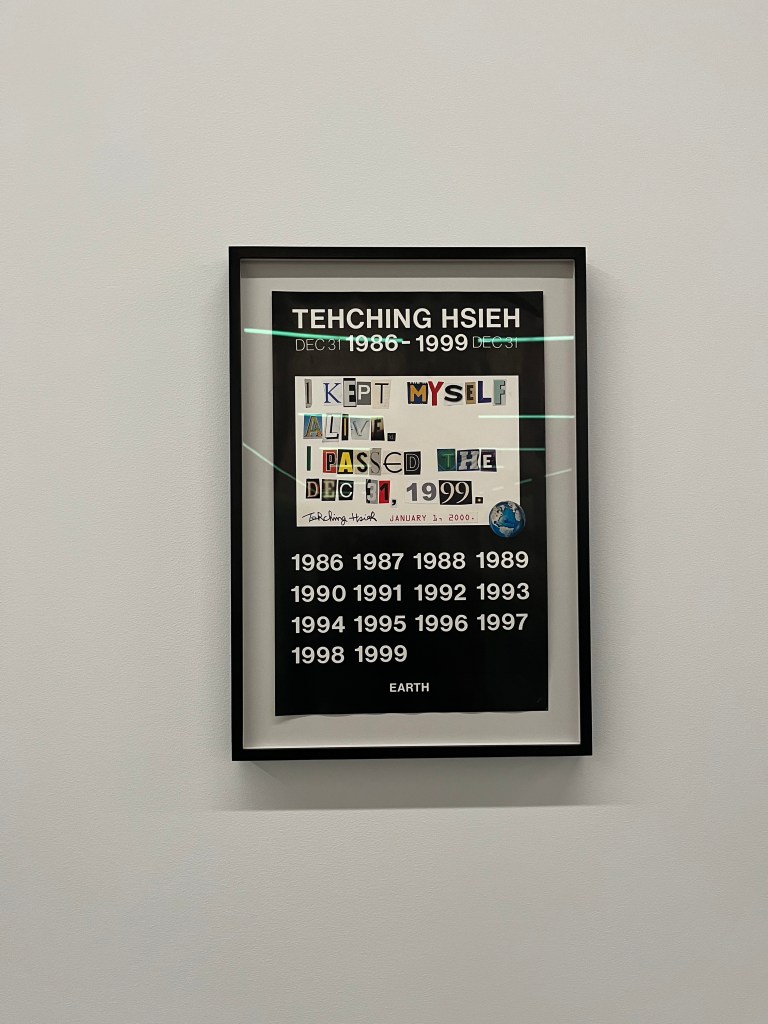

Nearly four decades ago, in 1986, Hsieh announced his “Thirteen Years’ Plan,” in which he would spend the next thirteen years creating art without displaying it publicly. Almost 25 years after completing the project, the artist gifted his eleven career-defining works to the Dia Art Foundation, contributing to the retrospective opening in fall 2025. This occurred eight years after his most extensive exhibition, “Doing Time,” at the Taiwan Pavilion of the 2017 Venice Biennale.

Tehching Hsieh’s practices resonate with the larger performance landscape of the 1970s and 80s. Examples include Marina Abramović’s Rhythm Series, which explored pain, endurance and the limits of the human body; Chris Burden’s Five Day Locker Piece, in which he locked himself in a locker for five days; and Shoot, in which he allowed himself to be shot. These works, as well as the rebellious and unruly bodies manifested in the work of Taiwanese artists during a similar time, centred around the notion of bodily endurance—a purely somatic and sensorial experience that surpasses concepts and ideologies.

Hsieh’s work, while sharing a resemblance with that of his fellow artists, is quieter, just like the artist himself, who is not exactly eloquent, especially when it comes to English. Unlike Abramović and Burden, whose bodies were often marked by visible wounds as signs of endurance and their art, Hsieh was different. He refused spectacles and was always composed. The only time that he actually made a scene was his arrest by the police while trying to stay outdoors for a year. He almost failed the performance by being taken into custody, which was indoors, but was fortunately discharged after a few hours and resumed his outdoor living. Most of the time, Hsieh was simply quiet, almost silent, doing his own thing and living his art, blurring the lines between art and life, much like time passes without notice.

In the exhibition, we saw the actual time clock he punched, the entire outfit Hsieh wore while he was on the streets for a year, and the rope that tied him to Montano. It was the wear and tear on these objects that showed the passage of time and offered a glimpse into what he experienced and survived.

Other traces of time can be seen in the photos of his Cage Piece and the hourly photos he took for his Time Clock Piece, in which his slowly lengthening hair was the obvious sign of time. From the photos that he and Montano took together with a rope in between, as well as those capturing Hsieh on the streets, we see that the scenery changed, sweaters replacing t-shirts, and holiday decorations appearing and disappearing—time was a co-performer and witness to Hsieh’s work. They choreographed silently.

Visiting the exhibition was also an embodied experience.

After learning about the exhibition, I immediately planned a short weekend getaway to Beacon. It was my first time visiting the small town and the museum. Unlike the exhibition’s fall 2025 press release, which described the town painted in different shades of yellow and orange, it was already winter when I arrived. I checked my heavy coat with the concierge and decided to explore the other exhibitions at the museum first. The architecture itself was art. As a former factory, Dia Beacon is one of the largest exhibition spaces in the US for modern and contemporary art. Its expansiveness is best suited to large-scale installations, paintings, and sculptures. The winter sunshine radiated through the large windows and skylights. Alongside the high ceilings, brick walls and industrial designs, the artworks blended into the environment as if they were grown from it.

The Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999 exhibition was located on the museum’s lower level. As I walked down the stairs, I felt the chill begin to creep back onto my sun-warmed body. The gallery was larger than the ones upstairs and divided into different spaces, each occupied by one of Hsieh’s pieces. Visitors entering each space were first greeted by a sign bearing a statement written in contract language defining the parameters of the piece. Then, there was a poster, sometimes with a calendar, documenting the performance’s timeframe.

There was a sense of composure and rigidity to Hsieh’s pieces, or, at least, the way they were presented. Contracts, calendars, indexes and photos—the repetitiveness was somehow curatorially satisfying. The first big surprise hit when entering the space of the “No Art Piece.” It was empty, literally. The aforementioned items that had occupied the white walls in other spaces were nowhere to be seen. The only things in sight were the statement of intention and the unmarked calendar from 1985 to 1986, alongside the overly blank walls and the large pillars standing in solitude.

The final space, designated for Hsieh’s “Thirteen Years’ Plan,” was even more impressive. It was a massive corridor reminiscent of those in vacant underground parking lots, with an exposed ceiling, concrete flooring, and pillars on each side leading visitors from one end to the other. The space itself was a literal manifestation of Hsieh’s work. Hsieh described his art as an iceberg: the visible works are only the tip, while the vast, unseen mass below represents the creative process he has developed over many years through time and action. While walking through the corridor, which was unaccompanied by any visible “art,” we could almost feel their presence filling the space. The stroll also resembled the journey, with Hsieh taking the same roads and at the same pace, guided by a clear sense of direction and purpose.

I slowly unwrapped the arms that had been around my body and felt myself finally warming up from the walk. Time, space and sensoriality all merged into one. The exhibition was embodied, just as Tehching Hsieh’s work was.

As of 2025, it has been 25 years since Hsieh last made art visible to the public. This period will soon exceed the amount of time he spent making art, though perhaps only on paper. For Hsieh, art and life are inseparable. This is not so much a statement as it is a way of life. He lives art.

Chee-Hann Wu is an assistant professor faculty fellow in Theatre Studies at New York University. She received her Ph.D. in Drama and Theatre from the University of California, Irvine. Chee-Hann is drawn to the performance of, by, and with nonhumans, including but not limited to objects, puppets, ecology, and technology. Chee-Hann’s work has appeared in Puppetry International, Asian Theatre Journal, International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, and other places. Her most recent research explores video games, VR, and artificial intelligence through the lens of theatre and performance.