Written by Chee-Hann Wu.

Image credit: 青鳥行動 by 苦勞網/ Flickr, license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Thousands of demonstrators surrounded Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan late into the night on Tuesday, May 21, to protest controversial parliamentary reforms led by opposition parties that together hold a majority of seats in the Legislative Yuan. President Lai Ching-te’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and administration are trying to prevent the opposition from pushing through measures to expand lawmakers’ investigative powers over the government.

The amendments introduced by the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) incited significant outrage. These amendments would empower lawmakers to summon private citizens, enterprises, or government officials for questioning, with non-compliance potentially resulting in criminal charges. Additionally, individuals questioned would be obligated to provide responses and disclose information, even if it pertains to sensitive state or enterprise secrets. Protesters and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) raised alarms that this could jeopardize national security by compelling individuals to disclose information, even if it involved sensitive state or enterprise secrets. In response to the lack of transparency in how the reform bill was handled, protesters demanded its withdrawal and took to the streets. The demonstration concluded around midnight on the 21st, only to resume three days later on the 24th, drawing tens of thousands outside the Legislative Yuan.

Signs and slogans are central to social protest and can convey a variety of messages— advocating for democracy, justice, equality, and other larger ideas; expressing emotions such as anger, frustration, joy, or hope; providing access to individual or collective feelings; creating solidarities; and also showing creativity.

In addition to “No discussion, no democracy” and “I despise the parliament,” the most commonly used signs and slogans of this bottom-up demonstration, later termed “Blue Bird Movement,” we witnessed many highly creative (and aesthetically pleasing) logos, meme-like signs and slogans that referenced popular culture, eliciting a knowing smile or a laugh from people who knew the origin of the expressions. These signs also show how protesters connected the political message and advocacy to their personal interests.

“I’m young, scrappy and hungry. And I’m not throwing away my democracy,” reads a sign held by a high school student. The slogan is taken from the lyrics of the musical Hamilton‘s “My Shot,” with the last word slightly changed from “shot” to “democracy.” Next to the words are two pictures of Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the book, music and lyrics and played the protagonist Alexander Hamilton in the 2015 off-Broadway and Broadway versions of the musical. Alexander Hamilton was an advocate for the American Revolution and later served in the American Revolutionary War at a very young age. This high school student’s sign shows that participation in political advocacy is not just for adults and that the issues addressed are just as important to young people.

Image credit: @brianhioe/X (Twitter).

Manga and anime works are also highly meme-able. Characters from Ojamajo Doremi and Attack on Titan were seen on the signs with different slogans of mockery or sarcasm (Figure 2). Another sign uses a classic slogan in this demonstration, “I despise the parliament”, but attaches an image of Anya from another popular Japanese manga and anime SPYxFAMILY giving the side-eye. Anya on the sign visualizes and highlights the feeling of disapproval and despise shared by many protesters.

Image credit: Public domain.

Coincidentally, two protesters were captured using the same reference on their signs with different designs and slogans, both inspired by the recent song “Good Night Ojosama“, which has taken over the Internet in Korea and worldwide. The song is a parody by two Korean entertainers, ASMRZ (TANAKA, NEEDMORECASH), of Japanese butlers as seen in butler cafes, a counterpart to maid cafes in Japan. In these cafes, waiters dress as butlers and serve patrons in the manner of aristocratic domestic servants, addressing them as ojousama (my lady) or ohimesama (my princess).

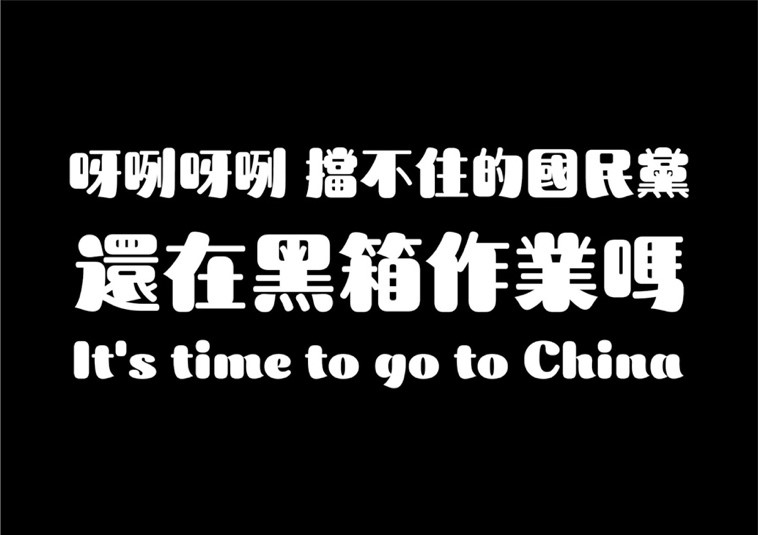

In the parody song, ASMRZ sings in both Japanese and Korean with Japanese intonation and occasionally in English. The song has very simple lyrics and a straightforward meaning, which is to persuade their ojousama to go to bed. The catchiest part of the song is “yare yare”, a Japanese interjection used when a person sighs or disagrees but in a loving way, indicating the patience of the person using the interjection. After “yare yare,” the song goes, “It’s time to go to bed”. References to these two lines were seen on the signs in this demonstration.

One of the two signs has a simple design with a black background and the words in white: “yare yare, unstoppable KMT. Still doing black box? It’s time to go to China” (see Figure 4). Another sign has a similar design with a black background and the words “yare yare. Stop it, blue and white. My lady does not want to sleep. The sign also has an exquisite painting of one of the entertainers dressed as a butler. What is most fascinating is that in a news photograph, a person holding the sign has deliberately done their hair to look like the character painted on the sign. It is like a multilayered role-play—the protester is cosplaying the Korean entertainer who is cosplaying a Japanese butler.

Image credit: @baron_hq/X (Twitter).

In fact, in addition to the protesters showing their creativity through signs and slogans, many people are providing designs and generously sharing their artwork for anyone to print and distribute for free on social media (Figure 5). The first “yare yare” slogan was actually created by @baron_hq on X (Twitter), along with other slogans, including one that reads “No freedom, no BL. Paying attention to the black box bill is caring about the future of your CP.” Another similar sign by @keiaku writes, “Oshi no CP—Democracy X Taiwan” (wotui de CP; the CP I support).

Image credit: @keiaku/X (Twitter).

A journalist captured a sign in the movement that has a bright pink background and sparks with semi-animated figures and names of Fu Kun-chi and Han Kuo-yu (Figure 6), the current KMT caucus convener and president of the Legislative Yuan, respectively. “Oshi no black box” (wotui de heixiang; my favourite black box) was written on the sign in a similar font as the world-popular Japanese manga and anime Oshi no Ko. The entire design of the sign either imitates that of Oshi no Ko or can be understood from a BL lens. Anyone recognizing the reference would certainly laugh seeing the cutified Fu and Han in a Japanese idol style.

Image credit: @catsfinger/Facebook.

The slogans above probably make no sense to anyone without context. The BL here is the abbreviation for Boy’s Love, a genre of Japanese manga that features romantic and sexual relationships between male characters, originally produced and consumed mostly by women. CP means couple in the works. What does BL have to do with freedom?

In recent years, China has imposed several bans on BL novels and dramas, also known as danmei. China once had a thriving danmei community of creators and consumers. For example, Jinjiang Literature Town, the largest online women’s literature platform, has an extensive collection of danmei novels, many of which have been adapted into films and TV series. BL fandom thus expanded beyond the online platform and became mainstream. However, its popularity soon led to censorship and multiple bans, as the state considered the genre to have “deformed tastes”, a “harmful culture” that could incubate false values, eroticism, violence, and other prohibited content. Many creators then reinterpreted their works as being about bromance or “socialist brotherhood” and hid the BL-ness behind such a facade. Despite the change, it is still believed that some creators of BL content, many of whom were seen in Jinjiang, have been arrested and sentenced.

The freedom of BL can be seen as the epitome of creative freedom in general. BL lovers in Taiwan share the concern and protest against the amendments to the bill by lawmakers who favour closer ties with China. Therefore, in order to continue to support their favourite CP, BL lovers need to gather and express how the bill, although seemingly irrelevant to their interests, can harm BL and the entire creative community. The creator of the second slogan invited fujoshi and fudanshi (fans of BL) to march on May 28 and turn it into a large-scale oshikatsu, an act of support for someone you particularly like.

In addition to BL, we also saw the presence of K-pop fans in the movement. One video showed a protester standing on the back of a truck and saying that he had never been lucky enough to get photo cards of his favourite K-pop group members (which were randomly given out when one bought a CD). They went on to say, “Still, photo cards can be bought, but democracy is not for sale.”

Finally, a sign takes a different approach to commenting on the controversial infrastructure project with a K-pop reference. The sign reads: “We can buy Hybe+JYP+YG+SM with two trillion dollars (Figure 7). The slogan is a humorous response to three bills proposed by Fu Kun-chi and others that would require the government to extend the high-speed rail system to the east coast, build an expressway connecting Hualien and Taitung counties, and extend the Shuishalian Freeway to Hualien. Based on internal sources and calculations, the DPP caucus estimated that completing these large-scale infrastructure projects would cost more than NTD2 trillion (US$61.72 billion).

Image Credit: @catsfinger/Threads.

The protestor’s presence was in response to the hashtag posts on Threads “Before being a fan, I am Taiwanese”, of which people shared why fans should protect Taiwan’s democracy as a way to sustain our freedom in supporting our favourite idols, resonating with the BL case. It is also likely that the protester holding the sign was trying to explain to other K-pop lovers how much money two trillion dollars is—more than the combined value of the four largest entertainment companies in South Korea: Hybe (BTS), JYP (Twice, the group Chou Tzu-yu is in), YG (Big Bang and Black Pink) and SM (Super Junior and Girls Generation). More of her story can be read in this article on Mirror Media.

In short, these signs and slogans reference various popular cultures and show how people engage and connect with political issues in different ways. At the same time, they demonstrate both exclusivity and inclusivity—exclusivity in the sense that only people with knowledge of the original references can decode the message and inclusivity in the sense that anyone, regardless of interest or background, can be a part of this conversation and collective action about our nation’s present and future. Grassroots creativities also grow when people with different backgrounds and expertise join in, just like the musical manifestations of mockery—the universe of “The Hymn of the Great Scallion—and .”Most importantly, they highlight the creative nature and diverse forms of engagement in social movements.

Chee-Hann Wu is an assistant professor faculty fellow (postdoc) in Theatre Studies at NYU. She received her Ph.D. in Drama and Theatre from the University of California, Irvine. Chee-Hann is drawn to performance by and with nonhumans including but not limited to objects, puppets, ecology, and technology. Her current book project considers puppetry a mediated means to narrate Taiwan’s cultural and sociopolitical development, colonial and postcolonial experiences, as well as Indigenous histories. Chee-Hann’s most recent work explores video games and VR through the lens of theatre and performance.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Bluebird Movement: Legislative Reform Protests in Taiwan’.