Written by Ting-Sian Liu.

Image credit: yutingchouart / Threads.

Social movements in Taiwan have developed over 30 years with a different set of agendas achieved through various movements. Taiwanese feminist movements, developed alongside Taiwan’s democratisation, have also achieved institutional success since the 2000s after the Democratic Progressive Party came into power. State feminism, meaning feminists actively work with and within state institutions, provides the institutional and legal groundwork of gender equality laws in Taiwan. However, a state-centred approach to gender and sexual harassment must be complemented by a grassroots approach that confronts the general public’s understanding and discussions on sexual harassment and micro-aggressions. Despite the establishment of three gender equality laws in Taiwan through the seemingly quite successful feminist movement over the past twenty years, we have not seen such widespread public discussions on sexual violence until the #MeToo movement in 2023.

The #MeToo movement in Taiwan burst out in 2023, with everyone of us in Taiwan still living in its ongoing legacies. Feminist and queer activists are reflecting on what has happened in that period, how we collectively are traumatised by what happened to every victim, and how we could heal and move forward. It is thus important to emphasise the politics of care when writing about the #MeToo movement in Taiwan. As a queer feminist, I ask: how could we avoid reproducing harm when writing on #MeToo? How could the writings on #MeToo and the movement’s emphasis on shared emotion be a space of collective healing? In this article, I explore how gender-sensitive and inclusive environments emerged from the recent Bluebird action, challenging past cultures of misogyny and discrimination. I examine how the #MeToo movement has contributed to creating new spaces for collective healing that push social movements in Taiwan forward in thinking about the politics of difference. Specifically, I seek to understand how the emerging manifestation of feminist politics and its attentiveness to differences in the Bluebird action remake the masculinised social movements into a space of collective learning and unlearning.

The use of sexual slurs in social movements

#MeToo movements have impacted various aspects of Taiwanese society, with one example being how they address the prevalent sexual violence in political spaces ranging from political parties to grassroots movement organisations. The scene of social movements is, in general, highly masculinised, particularly in movements linked with ethnonationalism, labour rights, and land-based movements. We could see that within social movements, the leader and the participants tend to be not only male-dominated but, most importantly, the prevalent use of sexual slurs in mobilising the crowd’s emotions.

Addressing sexual violence, including the use of sexual slurs and sexual metaphors to demoralise the opponent, is vital in moving forward to build a social movement for all. Take the Sunflower movement, for example. A decade ago, misogynistic slurs and objectification of women were quite prevalent within social movements and media coverage. When women appeared on the stage or in the media, they were either hypersexualised or desexualised. For example, referring to participants as “the goddess of student movement” demonstrated how the general public tended to praise women not through their ability but through the lens of sexual objectification. Another common example would be the often use of sexual slurs that discriminate against women, disregarding the gendered violence and trauma generated by sexual slurs. Frequently, women were also desexualised within social movements since social movements were constituted with a generalised or homogenised understanding of collective identity. Differences between actors and participants, including Gender and sexuality, tended to be overlooked since any call for attentiveness to difference would be read as “the separatist of the movement.” With the growing awareness of the #MeToo movement, the call for attentiveness to difference has reshaped how we approach the power relationships within various sectors.

The #MeToo movement in Taiwan started with a series of sexual misconduct of employees in the Democratic Progressive Party and soon spread across other sectors. On the one hand, it is shocking to see how within the seemingly “progressive” political circle lies underneath the tolerance of gender-based violence. On the other hand, we see that within certain social movements and movement organisations, women experience high levels of sexual harassment. Often, women were told to “tolerate the sexual harassment for the bigger picture.” Given the close ties between Taiwan’s political and activist circles, the masculinised culture of social movements is closely tied to the development of the #MeToo movement in Taiwan. Thus, looking into how people in the progressive circle tackle the exclusion and discrimination related to sex, Gender, sexuality, race/ethnicity, and nationality becomes another way of understanding how the #MeToo movement pushes social movement forward in Taiwan.

#MeToo movement and the politics of difference

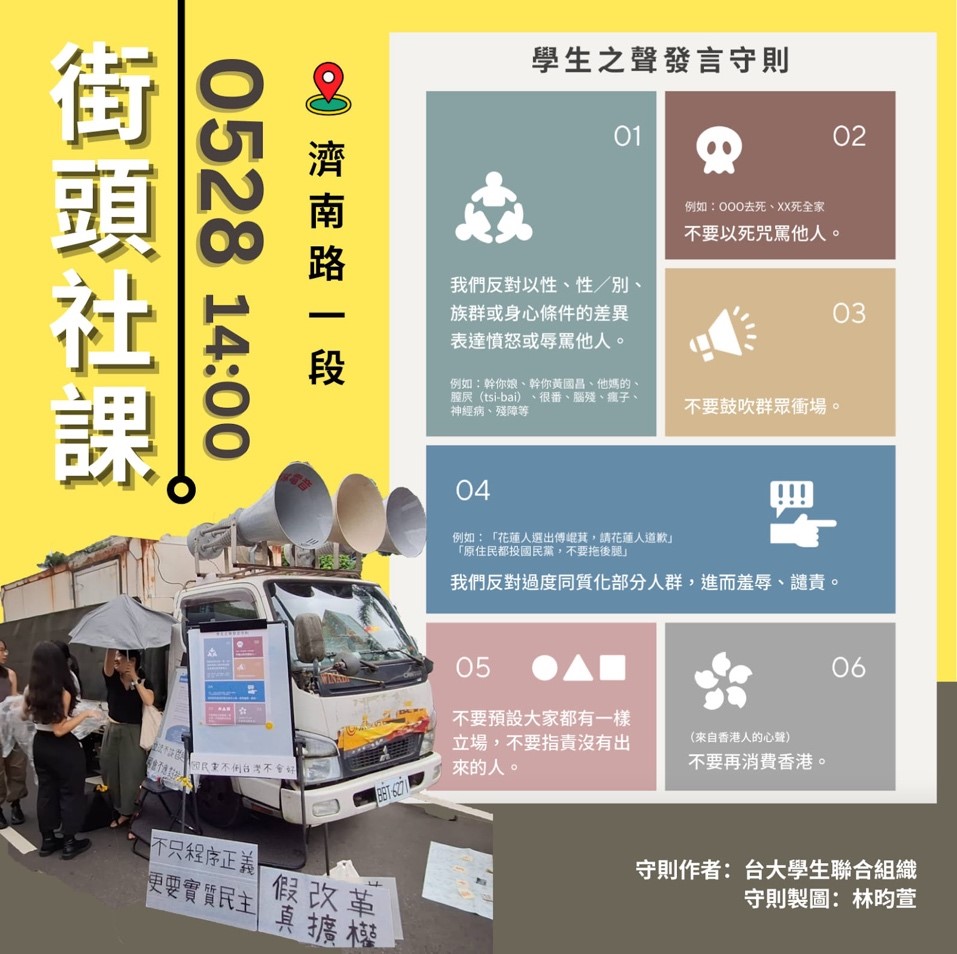

In the recent public mobilisation against legislative power abuse, or some would refer to the Bluebird action, we see the alternative ways of organising that arise from Taiwanese civil society. In the Bluebird action, protestors do not shy away from calling out misogynistic comments and sexual slurs made by the speakers. The decentralised way of organising arises from the Bluebird action that every protester has the chance to express themselves apart from the main stage, transforming the street into a classroom of collective learning and unlearning. One of the campaign trucks during the Bluebird action that draws my attention is ‘The Voice of students,’ led by NTU students. Collectively, those student organisations set up six principles to speak on the student truck (Figure 1):

“Firstly, we refuse to express anger or insult others based on differences in sex, Gender and sexuality, ethnicity, or physical and mental conditions. Second, we should not curse others with death. Third, we should not prompt the crowd to burst into the Legislative Yuan. Fourth, we oppose the excessive homogenisation of some groups of people and use such homogenisation to shame and condemn the entire group. Fifth, we should not assume everyone shares the same political stance and blame those who have not stood up. Sixth, voices from Hong Kongers: we should stop merely paying lip service to Hong Kong.”

Image credit: NTU Dalawasao / Designed by林昀萱.

Those six principles made by the students shed light on how adhering to the politics of difference helps build toward a more inclusive environment of social movements. In the statement, student organisations stated that they wish to create a social movement that is attentive to both Gender and ethnic differences, a movement that is not based on the logic of exclusion. Another statement made by NTU feminism on the night of the rally called for attention to the diverse and heterogeneous voices on the spot in order to create an environment that is friendly and inclusive to all. The statement also invites everyone to critically reflect on the privilege and the normativity of Gender, sexuality, and ableism produced through social movements. Within the statement, the adherence to difference and heterogeneity provides an alternative yet emerging approach to how we could organise and practice those values in social movements and daily life.

Social movements for the majority of the people

While social movements rely on the building of collective identity toward collective goals, the differences among participants are often flattened. A feminist reminder that emerged from the #MeToo movement in Taiwan is the prevalent gender-based violence across movement organisations, political circles, and activist scenes. There is a line often brought up through the Bluebird action: I don’t want a misogynistic Taiwanese Independence. This call echoes the #MeToo movement in 2023 when many pro-independence and/or progressive politicians are also the perpetrators of sexual misconduct. In the past, social movements tended to overlook the experience of women and other minoritised groups. However, with the development of social movements and the widespread #MeToo movement, the public has started to have wider discussions around sexual harassment and is more willing to either discuss or call out perpetrators or problematic statements directly.

Moving forward, it is worth noting how the concept of intersectionality plays a crucial factor in building a social movement that is inclusive to all genders, races, and ethnicities. While some would approach those six principles made by NTU students as being about “minorised voices” within the social movement, I proposed to think the other way around, where those six principles are actually for the majority of the people in Taiwan. This perspective recognises that everyone experiences different degrees of exclusion made by the systems of gender/sexuality, ethnicity, disability, and mental illness. Through centering around the voices and the needs of women and other marginalised groups, it reconfigures how we envision social movements.

Ting-Sian Liu (she/they) is a PhD student in Gender at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research interests lie at the intersection of sexuality, race and Gender, particularly looking into Indigenous queer subjects and queer activism in Taiwan. She can be reached at t.liu36@lse.ac.uk

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘The #MeToo Movement One Year On.’