Written by Meng Kit Tang.

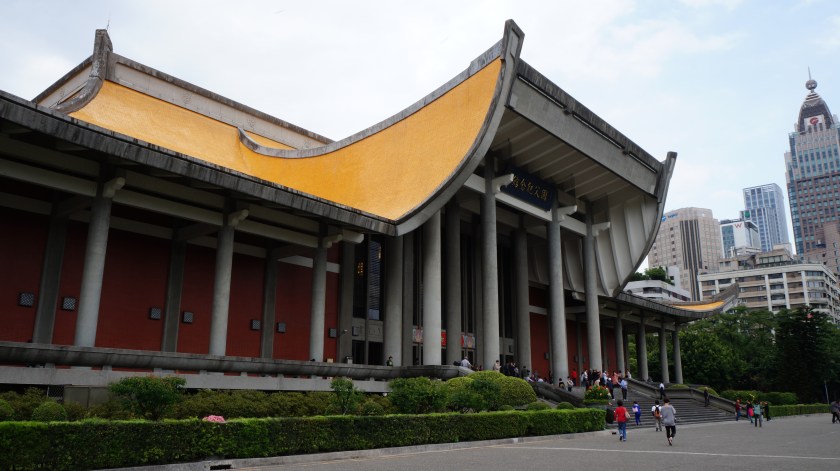

Image credit: Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall by カメラマン/ Flickr, license: CC BY 2.0.

Introduction: The Question of Chineseness

What does it mean to be Chinese, not merely as a bearer of ethnicity or a citizen of a state, but as a participant in a cultural and moral tradition? In today’s fractured global landscape, this question has assumed new urgency. The Chinese diaspora, spanning from Southeast Asia to North America, is grappling with an identity crisis shaped not only by immigration and multiculturalism but also by the ideological shadow cast by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Within Mainland China, culture has been politicised into propaganda; outside of it, cultural inheritance often becomes a casualty of geopolitics.

The struggle over “Chineseness” represents a battle over the moral meaning of belonging rather than merely a debate over history. Beneath the political slogans and historical revisionism lies a deeper tradition that persists. It grows from enduring values: civic responsibility, moral cultivation, and cultural continuity. These values, embodied most clearly in the legacy of Sun Yat-sen, offer a compelling framework for rethinking Chinese identity beyond authoritarianism, beyond nostalgia, and beyond fear.

The Distortion of Identity: CCP, KMT, and DPP

Modern Chinese identity has been distorted through three major forces, each reflecting a different failure to uphold the ideals of cultural integrity and civic virtue.

The Chinese Communist Party merges culture with obedience. Chineseness, in the Party’s narrative, connects directly to loyalty to the state. Patriotism becomes equivalent to ideological conformity. Ancient philosophers serve as tools for soft power; Confucius transforms into a brand. The past undergoes manipulation to justify a techno-authoritarian future rather than receiving genuine honour. This represents the instrumentalisation of Chinese civilisation rather than its continuation. The CCP reduces identity to spectacle and sovereignty, transforming a rich tradition into a tool of surveillance and control.

The Kuomintang (KMT), historically the party of Sun Yat-sen, has suffered an ideological drift. Its once-revolutionary republicanism has calcified into cultural conservatism. While the party still gestures toward its founder’s ideals, it rarely embodies them. Its vision of cross-strait peace is vague, its political energy spent defending the past rather than reimagining the future. In clinging to outdated notions of ethnic nationalism, it fails to inspire a pluralistic and civic understanding of Chinese identity.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Taiwan’s ruling party, has rightly emphasised democratic resilience and national dignity in the face of Beijing’s aggression. Yet in asserting a distinct Taiwanese identity, it often disengages from Chinese cultural roots altogether. To many in the DPP’s intellectual circles, Chinese symbols are reminders of past oppression – cultural elements to be discarded rather than reinterpreted. While understandable in a geopolitical context, this rejection risks turning Taiwan into a cultural orphan. It severs the island not only from Chinese authoritarianism, but also from the ethical and intellectual inheritance that Sun Yat-sen sought to modernise, not abolish.

None of these actors – CCP control, KMT confusion, or DPP detachment – offers a coherent, compelling model for what it means to be Chinese in the 21st century.

A Forgotten Compass: Sun Yat-sen’s Civic Nationalism

To find a meaningful alternative, we must return to the civic nationalism of Sun Yat-sen, whose vision remains both underappreciated and urgently relevant. His “Three Principles of the People” – nationalism, democracy, and livelihood – go beyond outlining a political system; they articulate an ethical project for collective flourishing.

Sun’s nationalism was inclusive rather than ethnic. He rejected racial essentialism, advocating instead for a shared civic identity built on mutual respect and cultural participation. He proposed naturalisation over assimilation; partnership over domination. His conception of China was a republic of equal citizens, distinct from both a Han ethnostate and a Sinic empire.

His democratic philosophy, while influenced by the West, was rooted in Chinese realities. Recognising the historical absence of democratic institutions, Sun proposed a transitional period of “political tutelage” to educate the populace in civic responsibility. Far from a justification for dictatorship, this was a scaffolding for democracy. Taiwan, with its five-branch government – executive, legislative, judicial, examination, and control, reflects this hybrid architecture. Direct elections, citizen recall, and referenda are not Western imports grafted onto Chinese soil; they are continuations of Sun’s effort to synthesise tradition and modernity.

Sun’s principle of livelihood (民生主義) is perhaps the most neglected today, yet it speaks directly to the socioeconomic insecurities of our time. He championed policies like land value taxation and anti-monopoly regulation; measures aimed at curbing inequality and ensuring social dignity. In an era where Chinese youth face unaffordable housing and precarious employment, these ideals are not relics but blueprints for reform.

Taiwan: A Living Inheritance

Sun Yat-sen’s vision lives most vividly in Taipei. Taiwan’s political system, while imperfect, has cultivated the institutions of self-rule that Sun envisioned. But more importantly, Taiwan embodies the moral aspiration at the heart of its project: to be Chinese means to deliberate and to flourish.

Taiwan’s democratic vitality extends beyond procedures. Its elections are frequent, its civil society vibrant, and its media combative. Citizens participate from a cultivated sense of civic duty. Mechanisms like referenda and recalls reflect a polity that trusts its people to shape their future.

Culturally, Taiwan has achieved what few modern states have: a balance of continuity and pluralism. Traditional Chinese festivals, temple rites, and Confucian values coexist with vibrant expressions of Hakka, Indigenous, and immigrant cultures. Language instruction includes Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien, and increasingly, Indigenous languages. Cultural memory is neither erased nor ossified; it is reinterpreted in freedom.

Moral solidarity is also visible in Taiwan’s everyday life. From neighbourhood volunteers to social movements advocating for marriage equality and labour rights, there is a tangible ethic of mutual care. Confucian values such as filial piety and social harmony have not been discarded; they have been democratised.

In this way, Taiwan represents a cultural Chineseness devoid of chauvinism, and a civic Chineseness full of confidence. It embodies a faithful reimagining of what China could have become had it remained true to the spirit, beyond the slogans, of its republican founding.

Beyond Borders, Beyond Nations

This redefinition of Chinese identity carries significant implications, especially for the global Chinese diaspora. In cities like Vancouver, Kuala Lumpur, Sydney, and New York, young Chinese face a dual burden: the external suspicion of being linked to Beijing, and the internal alienation from an identity monopolised by the state. In such contexts, the Taiwanese example offers liberation. It suggests that one can be Chinese by ethical choice rather than political compulsion; that culture exists as a living inheritance shaped by conscience and community rather than as property of power.

This also challenges Western observers to rethink their assumptions. Chinese identity exists separately from authoritarianism. Taiwan stands as a culturally rich society with its own democratic practice. Taiwan represents a site where Chinese tradition and democratic practice already coexist, offering a model for how ancient civilisations can flourish in modern contexts while maintaining cultural integrity and democratic values.

Conclusion: A Name Worth Keeping

To be Chinese, truly, means participating in a tradition that values justice, learning, and virtue. It means building a society where democracy feels familiar and where culture serves as conscience.

Sun Yat-sen’s legacy points toward a radical future, one in which Chinese identity becomes liberated from authoritarian rule and emerges as a project of ethical striving. Taiwan, by embodying this possibility, offers a positive model for Chinese modernity itself alongside resistance to Beijing’s ambitions.

In a century marked by anxious borders and manipulated identities, the deepest inheritance may be the hardest to claim: a name that transcends territory, and a culture that lives through freedom. That is the meaning of being Chinese, truly.

Meng Kit Tang is a master’s student in the MSc in International Relations Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. His research interests include cross-Strait’s relations, Taiwan politics and policy issues and aerospace technology. He currently works as an aerospace engineer.

you completely miss indigeneity. Pity.

LikeLike