Written by Carlotta Rose Busetto.

Image credit: 蔡英文 Tsai Ing-wen/ Facebook.

“Do clothes matter?” is a question that has not really been asked in research on Tsai Ing-Wen so far. Some have utilised music as a point of focus, but no one has thought to examine fashion as a political tool during her leadership from 2016 to 2024. As Jansens argues, clothing is often overlooked in political science due to preconceptions founded in gender bias and long-held beliefs of fashion not being relevant to the study of political leaders. However, existing studies on other female leaders across the globe demonstrate that including fashion into the picture is actually necessary. This is because examining clothes bridges the gap between the woman’s actual personality and the one she wishes to promote in politics.

In order to circumvent the lack of research on the role of fashion during Tsai’s presidency, this study (titled “’Do Clothes Matter?’: an Analysis of Taiwan’s First Female President through the Intersection of Fashion and Politics”) deploys four distinct methodological approaches, including social media analysis, news collection, image analysis and an interview with her stylist, Lin Zi-Hsuan (林子瑄). What will be introduced in this article will be a chapter analysing the former president’s use of Facebook during her two successful presidential campaigns (2016 and 2020) and examining how posting certain outfits online increased her electability.

Elections campaigns

Facebook is one of the most used social media platforms in Taiwan and is a favourite of the older generation. As a result, many politicians adapted and started using social media to reach voters. Tsai is no stranger to this. During both campaigns, in 2016 and 2020, the former president posted almost every day on Facebook. Apart from uploading election manifestos and campaign promises, her posts mostly include pictures of herself. As Facebook includes a timeline, each photo uploaded during both election cycles was analysed to observe any changes in her wardrobe choices according to location and time.

2016 campaign

The data collected from the 2016 campaigns was separated into two graphs (the same was done for the 2020 election cycle). The first one mapped the frequency of certain garments she was wearing in her Facebook posts, while the second one illustrated the distribution of gender-associated colours she wore.

Following from Han and Jung’s definition of feminine fashion as being “expressed through soft curves, lace, delicate patterns, light and soft materials, and pastel or bright colours”, sharp tailoring, heavy and bulky fabrics, strong patterns, and sombre muted colours were labelled as masculine fashion, both in garment and colour.

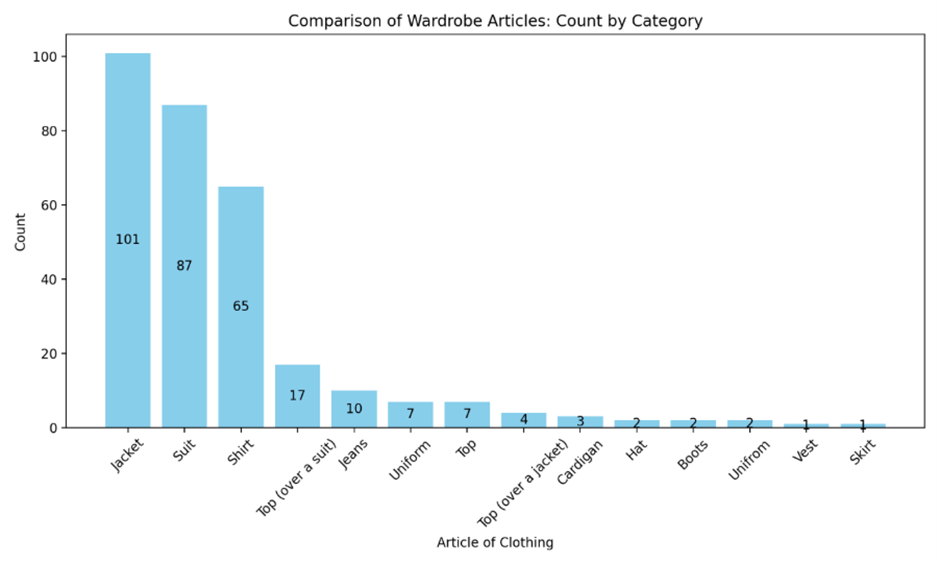

Figure 1: Graph illustrating the frequency of certain garments worn (2016)

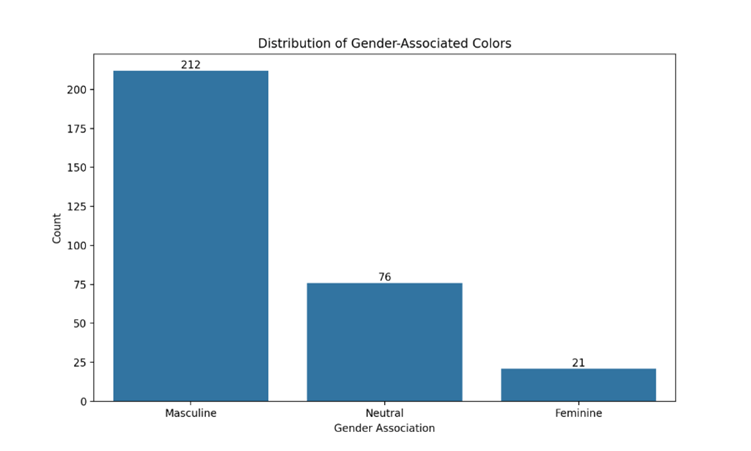

Figure 2: Graph illustrating the distribution of gender-associated colours (2016)

As Figure 1 illustrates, masculine garments such as jackets, suits and button-down shirts completely dominated Tsai’s wardrobe choices. Similarly, as shown by Figure 2, masculine colours, such as black, blue and brown, appeared over 212 times on her feed, thus entirely obliterating any feminine colours she wore.

However, the small presence of femininity, as seen in both graphs, was strategic and not random. In fact, as proposed by Jansens, “dressing-to-context” entails the deployment of womenswear or feminine details to conform to a certain situation that requires female politicians to show their feminine side, such as visits to schools, care homes, etc. The data collected for this cycle demonstrated that there were some moments when Tsai wanted her Facebook followers to see her feminine side. One example is a Lunar New Year greeting video she posted on 18th February 2015, where she is seen wearing a tight-fitting pink cardigan whilst holding her cat. Another is a photo of a market visit uploaded on 20th March 2015, where she is seen buying vegetables while wearing a bright yellow jacket. Therefore, “dressing-to-context” did occur in Tsai’s case.

2020 campaign

The difference between the 2016 cycle and the 2020 one was familiarity. People knew Tsai Ing-Wen after four years; she was not a stranger anymore. However, familiarity did not entail stagnation of her wardrobe choices. In fact, the data illustrate that in this campaign, her style became even more masculine.

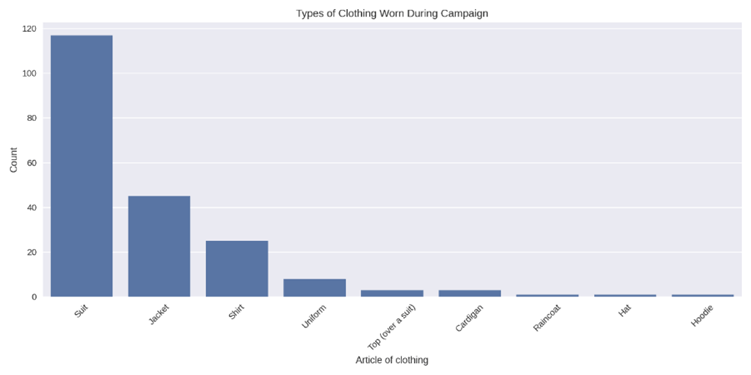

Figure 3: Graph illustrating the frequency of certain garments worn (2020)

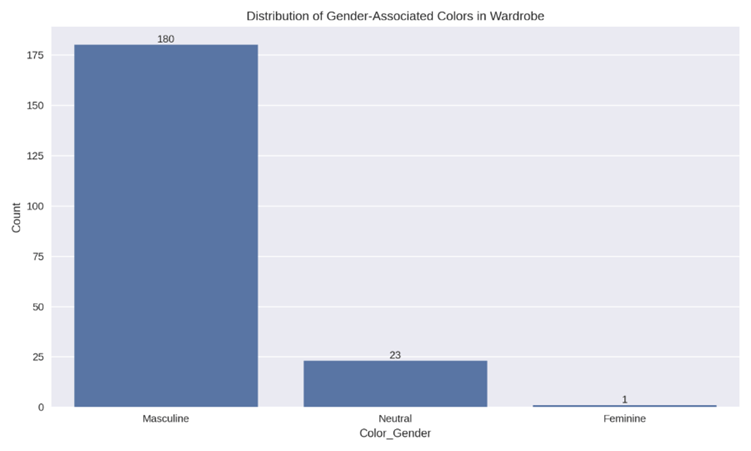

Figure 4: Graph illustrating the distribution of gender-associated colours (2020)

The locations of her posts also started to change. In contrast to 2016, her visits to army divisions increased, as did posts of her wearing the combat uniform posing next to soldiers. Doing so, Tsai strengthened her association with herself as head of the armed forces and of the state. In this campaign, she also visited more construction sites, where she would be pictured only in suits.

In contrast to the previous cycle, Tsai did not capitalise on femininity as she did before. In 2020, any feminine garments or colours worn at flower markets or visits to disabled children were replaced by a white jacket or a blue oversized button-down shirt, which concealed any feminine traits of her body and preserved an overall masculine image. One explanation for this can be found in the political context surrounding the campaign. Given the worsening of Cross Strait relations, she had to project a more assertive image that would reassure the public that she was “tough enough” to stand up to China, in spite of increased aggression. Therefore, her style became even more masculine for two reasons: 1. She did not want the public to forget her tough policies in her first term; 2. She was proposing to be even tougher in her second term.

During the interview with her stylist, Lin said that her main approach was not to change who Tsai was as a person. In fact, she said that dressing in a masculine way was the way the former president had always dressed, both in private and public contexts.

What can be deduced from Lin’s testimony and the data from both election campaigns is that the masculine image projected on Facebook was of Tsai’s own making. But also that, the former president performed masculinity through clothing to convey political capability and strength of character. This is because politics, even in dress, is dominated by hegemonic masculinity. As men in suits have long dominated politics, female politicians have had to adapt to the male dress code to be accepted. In fact, drawing from Yang’s understanding of hegemonic masculinity, Tsai adopted menswear because “politics … is considered to be rational, competitive, aggressive and individualistic”, while typical femininity is the exact opposite, so womenswear would not have conveyed the same effect.

Furthermore, the data also demonstrates that masculine fashion was deployed to blur the visual differences between herself and the men photographed beside her. In fact, in many photos uploaded to Facebook, Tsai is often not pictured alone, but with multiple male colleagues. Her extensive use of shirts and suits paired with block loafers in almost all of the photos does not make her stand out because of her gender. On the contrary, visually, her masculine clothes place her and the men beside on the same level.

Conclusion

In conclusion, clothes matter. Within a digital age where criticism is amplified by double, female politicians are increasingly cautious about potential wardrobe mistakes that could kill their career. Taiwan has undoubtfully caught up legislatively with gender equality; however, socially, women are still measured against Confucianist misogynistic standards. The subordination of women is not only visible in the domestic realm, but also in the public one, especially in politics.

This study’s findings show that Tsai was not free to wear what she wanted. As politics is dominated by men who wear suits and ties, venturing into womenswear could have potentially undermined her credibility and competence. This is because it is suits that are associated with professionalism, not skirts and dresses.

However, the findings are not limited to gender. Clothes matter because Tsai also utilised them to promote her own political agenda.

This study, therefore, concludes that Taiwan’s first female president cannot be fully understood if her use of fashion is not taken seriously. Clothes matter because they reveal gender inequality struggles, political strategies and what she was like as a person.

Busetto Carlotta Rose is a recent graduate of BA Chinese from SOAS, University of London. This article is an extract from her dissertation “’Do Clothes Matter?: an Analysis of Taiwan’s First Female President through the Intersection of Fashion and Politics.”

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘SOAS Taiwan Studies Summer School 2025‘.