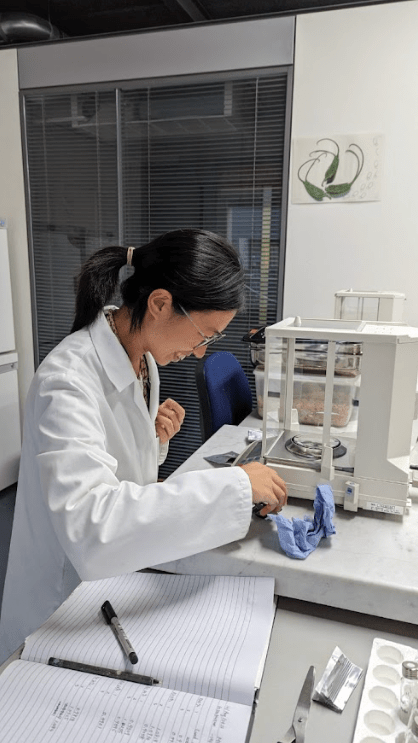

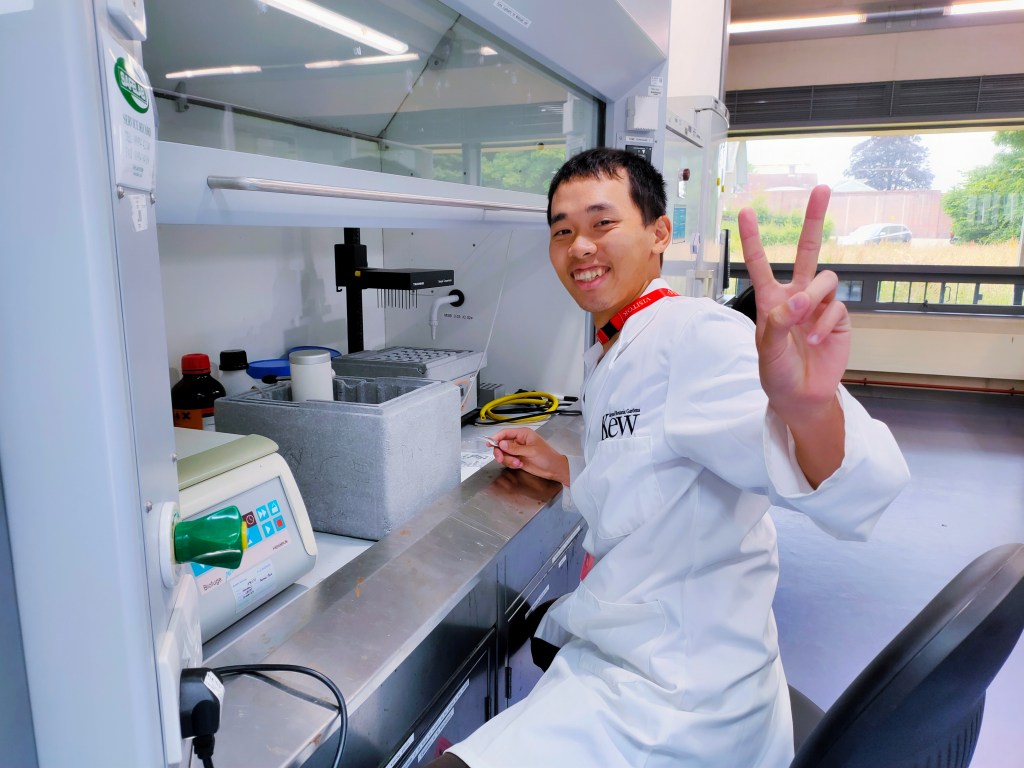

Written by Ni-Chen Lin and Chih-Wei Hsieh.

Image credit: authors.

A Shared Destination, Different Beginnings

We both studied at National Taiwan University (NTU), entering in the same year but following different paths in our academic journeys—Ni-Chen in the Department of Forestry and Resource Conservation, and Chih-Wei in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture. Our shared fascination with plants eventually led us to the same destination: the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

As student placements, we were both based at the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) at Wakehurst. Ni-Chen joined the Seed and Stress Biology Team as part of the first cohort of the NTU Overseas Internship Programme, shortly before completing her undergraduate degree, where she participated in the project “The Interacting Effects of Temperature and Moisture on Long-Term Seed Survival.” A year later, after Chih-Wei completed his master’s thesis on ornamental plant cultivation and breeding, he joined the second cohort of the same programme and contributed to the Global Tree Seed Bank project, “Unlocking Tree Seed Functional Trait Diversity and Stress Resilience to Enhance Ex Situ Conservation for Restoration and Use,” funded by the Garfield Weston Foundation.

Although we joined the same team at different times, our experiences reflected two distinct stages of the same learning journey. In the following sections, we share our perspectives—Ni-Chen’s first encounter with international research as an undergraduate student, and Chih-Wei’s reflections as a graduate student building upon two years of experimental work in floriculture. Through these parallel experiences, we began to see how similar roots could grow into different branches.

Ni-Chen’s Perspective – Discovering Global Botany as a Student

In 2023, my final year as an undergraduate, I found myself increasingly anxious about graduating. I was nearing the end of my degree, yet I still felt unsure about what lay ahead. Although I had explored several fields that genuinely interested me and gained some knowledge in each, I often worried that my skills might not yet form a coherent foundation for future professional or academic work. At that time, I was also unsure whether a career in academic research was something I might realistically pursue.

Then, almost by chance, I came across the announcement for the NTU Overseas Internship Programme — in its very first year. To my surprise, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was among the participating organisations, offering four positions across different departments. The news quickly spread among students in plant science, making it clear that competition would be intense. Still, I felt a mixture of excitement and apprehension: this was my last opportunity to step into something new and gain firsthand research experience in a world-class plant science institute. I applied for two positions, one with the Seed and Stress Biology Team at Wakehurst and the other with the Science Education Team at Kew.

Looking back, it may sound slightly odd, but even after submitting my applications, I worried whether I would be accepted. Fortunately, the outcome was positive — I was offered a placement with the Seed and Stress Biology Team and soon found myself on my way to the Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst.

During my placement, my main task was to conduct experiments on seeds stored under varying temperature and moisture conditions, gathering data to improve our understanding of how different types of seeds respond to storage stress. This research contributes to developing better long-term storage strategies for conservation purposes.

Our team fostered a warm and supportive atmosphere. My supervisor consistently encouraged me to learn new laboratory techniques and analytical methods, giving me the freedom to explore independently. Within this environment — built on her trust and occasional technical guidance from colleagues — learning through trial and error became not a source of stress, but an enjoyable and fulfilling part of the research process.

Everyone at the Millennium Seed Bank, including my colleagues, approached their work with a strong sense of purpose and commitment. Perhaps it was the knowledge that even the most repetitive experimental procedures directly contributed to the Seed Bank’s mission of conserving wild plant species for the world. Their patience and dedication were contagious, and I soon found myself imbued with the same sense of responsibility and enthusiasm.

The work environment itself was also engaging and thoughtfully designed. The ground floor of the building served as an exhibition space, separated from the laboratories by full-height glass panels. Facing the exhibition area, displays explained the step-by-step process of seed banking and introduced some of the experiments underway, such as periodic viability checks on stored seeds. Passing through the exhibition and returning to my workstation, I was constantly reminded: I was genuinely participating in meaningful work. The combination of these people, this space, and the visible connection to the Seed Bank’s mission provided me with abundant motivation and strengthened my aspiration to work within research institutions.

I must also mention how stunning Wakehurst is. The Millennium Seed Bank is often referred to as “Kew’s Wild Botanic Garden,” where I could take walks among trees and meadows at the end of each day. Being immersed in such a rich and diverse plant environment was a daily source of joy — a tangible reminder of the beauty and variety of plants, not only from the UK and Taiwan, but from all around the world.

I had often heard people returning from study-abroad programmes, exchange experiences, or research placements say that their horizons had “broadened,” yet I had struggled to imagine what that truly meant. Experiencing the Millennium Seed Bank firsthand, I began to understand. I witnessed the scope and vision of an institution that preserves and studies wild plant genetic resources without national boundaries. I could see how the staff’s work and the projects themselves transformed the idea of a “world-class conservation and research institution” from words into action.

Over the three months of my placement, I gradually came to appreciate how ambitious goals and complex organisational operations could be realised in practice — and this understanding steadily took root in my mind, shaping both my perspective on science and my own professional aspirations. The rich environment at Wakehurst, and the inspiring work at the Millennium Seed Bank, left a lasting impression — one that continues to remind me why research matters, and why curiosity must be carried forward wherever I go.

Chih-Wei’s Reflection – Growing Beyond the Seed Bank

A year after Ni-Chen’s placement, I joined the same programme, embarking on a similar journey but at a different stage in my academic path. Looking back, I had never imagined I would one day have the chance to join. The idea of interning at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew—a dream destination for any student in plant science—seemed almost unattainable, especially with only four places available. After receiving my bachelor’s degree, I had not yet found a clear direction for my future, so I decided to pursue a master’s degree in horticulture, focusing on flower breeding. That decision planted the first seed of my research journey. As I delved deeper into plant physiology, I developed a stronger sense of curiosity and appreciation for the complexity of horticultural science. The more I learned, the more I felt that simply continuing to work in this field after graduation would already be deeply fulfilling.

Yet deep down, I knew I wasn’t ready to stop there. Before finishing my graduate degree, I decided to give myself one last challenge—to apply for this programme. By what felt like a fortunate turn of fate, I was selected and offered the chance to spend three months at Kew’s Wakehurst Place. Holding that offer letter felt like holding a ticket to a lifelong dream—but as I would soon learn, it was only the beginning.

Although previous participants from the first cohort kindly shared their experiences, the prospect of living and working abroad for the first time still filled me with uncertainty. I wondered whether I could understand the British accent, adapt to daily life and food, or fit into an international research environment. I even spent the flight reading recent papers from my assigned research group, trying to prepare myself for what lay ahead.

The moment I arrived at Wakehurst, I was astonished. It was, in every sense, a dream workplace— where work felt less like a duty and more like a shared passion. Every difference I observed, from daily routines to research culture, reshaped my imagination of what work and life could be. Our team included scientists and students from the UK, the Netherlands, Brazil, Italy, India, and Nigeria. Collaboration was not just encouraged but celebrated; everyone contributed ideas and expertise freely, and progress felt collective rather than competitive.

The laboratory culture at the Millennium Seed Bank was warm and balanced. We had scheduled tea breaks every morning and afternoon, where discussions about experiments easily blended with stories about local traditions or travel. There was no strict time-clock system; instead, we managed our own 36-hour work weeks and adjusted schedules according to experimental needs. Senior researchers could even work from home several days a week, maintaining constant communication through online meetings. What impressed me most was how this culture of trust and cooperation made the team more efficient and creative than any individual effort could achieve.

This experience was far more than participation in a seed physiology project — it was a transformation in perspective. It expanded my international outlook, encouraged me to communicate confidently with foreign researchers, and motivated me to use platforms such as LinkedIn to build professional connections. Looking back, I now realise how pivotal that decision was. What I gained from Kew was not only a set of photographs but also a deeper sense of understanding, imagination, and quiet change that continues to shape how I see both science and life.

Looking Ahead — From Kew Back to Taiwan

Our time at Kew continues to shape how we work and think in Taiwan today.

After returning to Taiwan, Ni-Chen graduated from NTU. As for Ni-Chen, through her time at the Seed Bank, she realised how much research culture depends on openness — to questions, to collaboration, and to failure. This insight inspired her to take the first step on the academic route — to pursue a master’s degree at NTU, seeking further training in botany and ecology. While preparing for entrance exams and applications, she also became involved in environmental education, rediscovering her enthusiasm for education-related issues. Her current research integrates plant diversity and botanical knowledge with the development of museum-based educational programmes.

Chih-Wei, meanwhile, passed the Senior Civil Service Examination and joined the Floral Industry Innovation Center under the Ministry of Agriculture as an Assistant Researcher. Each year, he is required to propose research projects and achieve key performance indicators that often align with national agricultural policies. Compared with the flexibility he experienced at Kew, Taiwan’s governmental research system offers less autonomy and seldom involves foreign scholars or cross-disciplinary collaborations. Yet the three months at Kew completely transformed how he approaches research and teamwork. The experience encouraged him to seek collaboration beyond his own field and to take on new responsibilities, such as coordinating visits and exchanges with international guests.

Although our career paths have taken different directions, we both continue to draw upon what we learned from our time at Kew. The experience taught us that scientific work extends far beyond experiments and data — it is about curiosity, collaboration, and care for the living world. Back in Taiwan, we carry with us the perspectives that Kew helped cultivate: an openness to learn across disciplines, a belief in the value of connection, and an awareness that even small acts of research or education can contribute to something larger. While systemic change takes time, we believe personal transformation begins immediately — and that each step, however modest, brings us closer to a more interconnected and sustainable future.

Ni-Chen (Alice) Lin (林妮臻) is currently an MSc student at the Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, National Taiwan University. Her research focuses on science education from a museum perspective. She graduated from the Department of Forestry and Resource Conservation at the same university and worked as an intern at the Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst during the summer of 2023. She can be reached at linnichen.alice@gmail.com.

Chih-Wei Hsieh (謝智為) is currently an assistant researcher at the Floral Industry Innovation Center, Ministry of Agriculture, Taiwan. He holds both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree in Horticulture and Landscape Architecture from National Taiwan University. His research focuses on flower breeding, greenhouse horticulture, and smart agriculture. In 2024, he participated in the NTU Overseas Internship Programme at Wakehurst, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He can be reached at cwhsieh@fiic.gov.tw.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Seeds of Exchange: Stories from the Kew-NTU Collaboration‘.

If you are interested in working at Kew, the Global Pathfinders initiative recently launched a program including six 6-month fully paid opportunities at Kew. More information can be found on page 6 of the website under codes G-8-34 to G-8-39: https://twpathfinder.org/overview1830.