Written by Tzu-Li Yang.

Image credit: author.

As an undergraduate, I was trained as a forestry student in Taiwan before moving into life science for my master’s degree. In our plant taxonomy course, lecturers often referred to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – and especially the Herbarium – as an almost abstract benchmark for botany and plant collections. As a first-year student, I already knew that this was one of the leading institutes in the world and often imagined how experts actually worked there. In 2024, I had the opportunity to see it in person as part of the second cohort of the NTU Overseas Internship Programme. Encouraged by a fellow student from the first cohort, Wei-Han Fang, I applied for a placement in the Herbarium. This article reflects on what I actually saw and did at the Kew Herbarium – from routine curation work to building trait datasets and experiencing a very different work culture – and how these encounters reshaped the way I think about botany and my own future role in Taiwan.

Working behind the scenes in the Herbarium

The Kew Herbarium, my main working site, is one of the largest herbaria in the world, holding around seven million specimens and representing about 95% of the world’s vascular plant genera, accumulated over more than 300 years. These specimens, collected from across the globe, are stored, catalogued and arranged to support research in taxonomy, conservation, ecology and sustainable development.

During my placement, I was assigned several routine tasks that kept this system running. In the weekly ‘Family Sort’ session, newly arrived specimens from Asia were checked, roughly classified and routed. Even when preliminary labels were already attached, the simple act of handling so many sheets trained my taxonomic intuition. It revealed patterns in where the material was coming from and which groups were being collected. I could go through a large number of specimens in a short time and pick up identification tips from colleagues as we worked side by side.

I was also involved in curation after sorting. Once specimens had been mounted and imaged, they needed to be separated into genera and geographical areas. Then they placed them into the correct folders and cabinets for their long-term storage. This work tested my sense of taxonomy. When names had changed because of new taxonomic evidence, specimens had to be re-filed and their records updated, so I learned to check current classifications and synonyms in Plants of the World Online (POWO), the global plant database maintained by Kew.

Building trait datasets: treating specimens as structured data

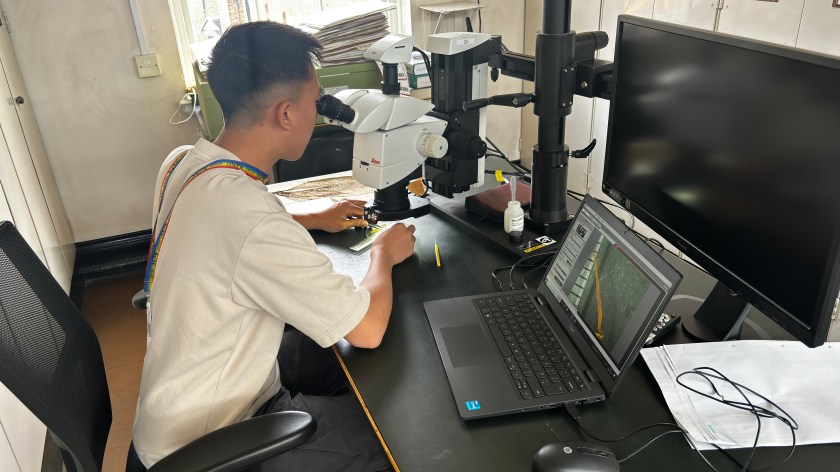

Specimens are not only collected and stored in cabinets; they are also crucial for everything that happens afterwards. Most of my time in the Herbarium was not spent in the cabinets but at a booth, turning individual sheets into structured records. Under the guidance of my mentor, Dr Eve Lucas, who leads the Integrated Monography team, I was assigned to build trait databases from specimens. The first project focused on phylogenetic research in Cyrtandra from New Guinea with a PhD student, Cecil Lee-Grant. Working from physical specimens, I built a trait dataset that could later be combined with molecular data. For each sheet, I recorded morphological traits of leaves and flowers – from phyllotaxis and leaf length to width, and indumentum of bracts, discs and corollas – as well as collection details and geographical information from the labels. In practice, this meant using a microscope and ImageJ to capture fine-scale measurements and later using R to explore patterns in these trait data. The material did not come only from the Kew, but also from other institutions in Paris, Lyon, Leiden, Berlin and the Bishop Museum. We also visited other herbaria, including the Natural History Museum in London, to study specimens in person and experience different collection environments. For the first time, I was not just looking at plants but also deciding how they should be represented as data.

A second project, within the KewBridge initiative, pushed this data-centred approach further. KewBridge aims to prioritise, build and document datasets that can be used to train machine-learning applications. In my part of the project, I helped mobilise taxonomic data from The Kew Tropical Plant Families Identification Handbook, focusing on Myrtales. Instead of working directly with physical sheets, I used digitised specimen images from GBIF to extract and standardise information so that it could be used for image-based identification. On a practical level, this meant deciding which traits really mattered, how to make records consistent across institutions and how to flag doubtful or incomplete entries. It felt less like classical taxonomy and more like building a scalable data pipeline on top of existing collections.

To keep this work transparent and reusable, I documented the workflow and simple procedures in a public GitHub repository. Writing down each step – from selecting images and fields, through basic quality control, to the final dataset – made me think more carefully about reproducibility and about how future students or partners might reuse or improve the process. These projects turned the Herbarium, in my mind, from a solid archive into a living data system, and made me realise that, beyond fieldwork, helping to design data structures and workflows can also support Taiwan’s botanical research in the long term.

Working and learning in a different cultural environment

Drawing on my undergraduate training in forestry, most of the practical work in the Herbarium was not technically difficult for me. At the beginning, I was eager to prove myself by working hard and being visibly productive – a mindset that I think many interns from Taiwan share when entering a new environment. My mentor and colleagues often told me not to work too hard and also stay too late, which initially made me worry that I was not doing enough. Over time, however, I realised that my worries were unfounded. As an intern, I was repeatedly reminded that learning came first and that long hours were not a measure of commitment. This attitude towards work-life balance created a sense of psychological comfort that made it easier to ask questions, admit and try new assignments.

Another memorable aspect of Kew was its tea culture. The tearoom became an informal classroom where I could meet colleagues from Europe, Africa and the Americas. Our conversations ranged from current research projects at Kew to weekend plans and holiday stories. These gatherings were not only social occasions but also opportunities to exchange ideas, learn about different approaches and become more confident using English in a relaxed setting. Together, these experiences have also changed how I think about my future contribution in Taiwan: not only working in the field, but helping to design data structures and workflows, and to build learning spaces in botanical institutions.

Conclusion

Despite some challenges, my placement at Kew was a genuinely valuable experience. Although herbaria in Taiwan are not on the same scale, it gave me a clearer view of how collections can be developed as data systems, through better digitisation, standardised traits and collaborative workflows across institutions. It also showed me that much of the scientific knowledge we rely on still comes from these historically rooted institutes, now supported by modern data practices. Looking ahead, I hope what I learnt at Kew can still benefit botanical and conservation work in Taiwan, either by sharing these experiences with others or by applying a stronger awareness of collections and data in whatever roles I take on. If my summer in London had one lasting effect, it is this conviction. With the right data practices and collaborative habits, even relatively small systems can deliver a disproportionately large impact.

Tzu-Li Yang (楊梓立) is a master’s graduate in Life Science from National Taiwan University, with a research focus on photosynthetic pathways and ecophysiology in orchids. In 2024, he interned at the Kew Herbarium, contributing to the Cyrtandra traits program in phylogenetic studies and specimen sorting and curation. He can be reached at r11b21023@ntu.edu.tw or on LinkedIn.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Seeds of Exchange: Stories from the Kew-NTU Collaboration‘.

If you are interested in working at Kew, the Global Pathfinders initiative recently launched a program including six 6-month fully paid opportunities at Kew. More information can be found on page 6 of the website under codes G-8-34 to G-8-39: https://twpathfinder.org/overview1830.