Written by Isis M. Lee.

Image credit: author.

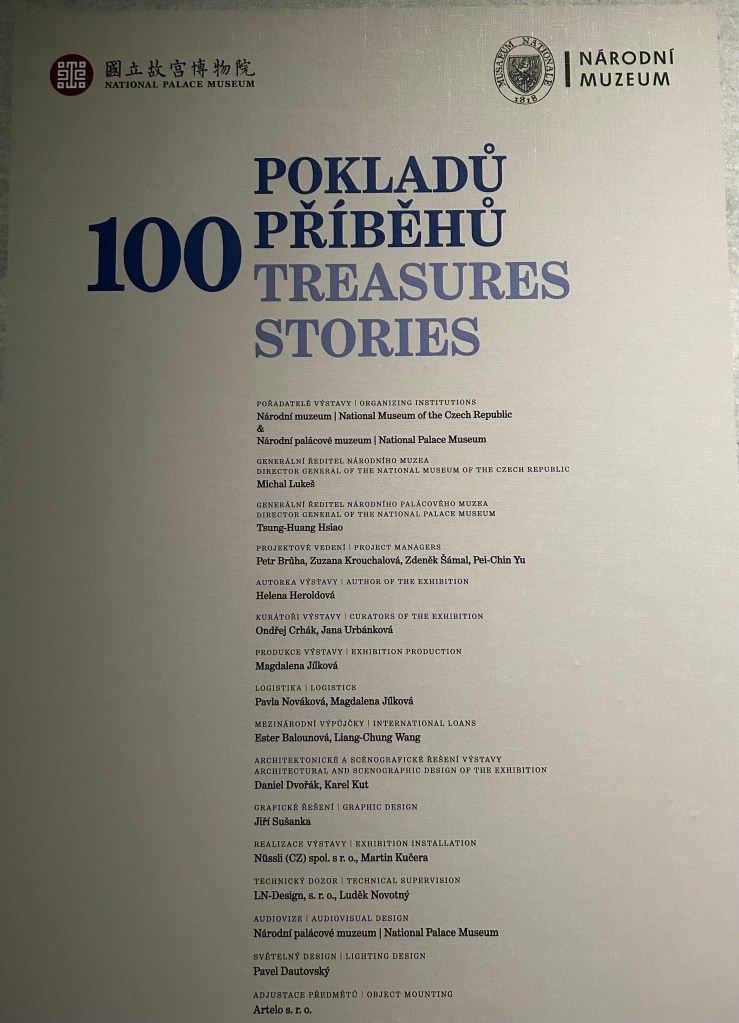

In September 2025, Prague welcomed an exhibition of 100 treasures from Taiwan’s National Palace Museum — an extraordinary cultural moment by any measure. Yet visitors quickly spotted something strange: not a single panel or caption mentioned “Taiwan.”

The artefacts had travelled thousands of miles from Taipei, but the fact of where — and under whose care — they are preserved was omitted. For a show meant to celebrate shared cultural heritage, it was an oddly hollow silence.

Over recent years, cultural ties between Taiwan and the Czech Republic have deepened significantly, supported by growing parliamentary engagement between the two democracies. In 2022, Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture helped establish a sister-museum partnership between the National Taiwan Museum and the Czech National Museum, renewing a relationship first formed two decades earlier. Against this backdrop, Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched its “Taiwan Culture in Europe 2025” initiative, with the National Palace Museum’s Prague exhibition positioned as one of its centrepieces.

Titled 100 Treasures, 100 Stories and running from 11 September to 31 December 2025, the exhibition brings together more than a hundred imperial artefacts — including the celebrated jadeite cabbage, rarely lent abroad and shown in Europe for the first time. But the omission of the National Palace Museum’s (NPM) origin and background was strikingly unorthodox for a professional exhibition. As a regular visitor, the author toured the full gallery in early November and noted that the interpretive silence carried an unsettling resemblance to cultural censorship in China, where works touching political sensitivities can vanish without explanation, even if it distorts the historical record. What is troubling here is that this silence did not take place in China but in Europe — suggesting that the PRC’s censorship now extends across borders and, at times, pushes democratic institutions into censoring themselves.

This was not a curatorial accident. CNN reported that threats were made regarding the exhibition’s security prior to the opening. And where threats exist, avoidance tends to follow. But the decision not to name Taiwan points to more troubling questions: why should acknowledging historical fact be considered a provocation? And where exactly do these risks and pressures come from?

To answer that, we need to revisit the history that the exhibition did not dare to tell.

The history that cannot be spoken

The NPM’s collection sits at the heart of a political story the PRC would rather forget. These artefacts — imperial paintings, bronzes, jadeite, and ritual objects — were moved to Taiwan by the Republic of China (ROC) government in 1948, during the Chinese Civil War, and a year before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) even existed. Acknowledging Taiwan in the NPM exhibition would therefore unsettle not only Beijing’s claim of historical continuity over Taiwan but also its more recent attempts to recast the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45 as a victory attributable to the PRC — despite the fact that the ROC government fought that war and governed China at the time.

Ironically, that relocation almost certainly saved the collection. Had the objects remained in mainland China, many could have been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, when countless artefacts and temples were condemned as relics of “old culture.”

This is the part of the story that Beijing finds intolerable. It undermines a core claim of the PRC’s political narrative: that Taiwan has always been part of China under its rule. The museum timeline itself shows the opposite — that the PRC has never governed Taiwan.

No other set of objects from Taiwan carries this much political weight, which is precisely why their presence in Prague triggered such sensitivity.

The Czech Republic made the exhibition possible — but at a cost

What made the exhibition possible in the first place deserves acknowledgement. The NPM only sends its treasures abroad under extremely strict conditions. Host countries must provide judicial immunity from seizure, ensuring the artefacts cannot be confiscated or held for political disputes.

In 2024, the Czech Parliament amended its cultural heritage law to include explicit immunity-from-seizure provisions. This was no small gesture. It showed a genuine commitment to cultural cooperation with Taiwan and required significant coordination by Taiwan’s government and the museum.

If anything, the Czech government took a courageous step. But courage from governments is only half the story. When institutions anticipate backlash from Beijing — even within democratic societies — the pressure to avoid controversy shifts onto museums, curators and cultural administrators. Compared with other major cultural events staged under Taiwan’s government in Europe, the NPM exhibition stood out for how deliberately it was stripped of context. It remains unclear who made the decision, but the result is unmistakable: a pre-emptive erasure of Taiwan from the curatorial narrative.

In other words, the chilling effect began before the exhibition even opened. The absence of Taiwan on the walls of a European museum was not the product of historical ambiguity; it was the product of intimidation. The security threats directed at the exhibition made clear that the concerns were not imagined but grounded in real pressure.

How self-censorship is quietly creeping into cultural institutions

Democratic societies across Europe are already discovering that national cultural institutions — long assumed to be neutral spaces of scholarship and public learning — have become microcosms of geopolitical struggle. The omission of “Taiwan” from the Prague exhibition is a clear example. What should have been a straightforward act of naming provenance instead became a calculated silence, shaped not by curatorial judgment but by fear of political repercussions. Even in open societies, institutions find themselves hesitating over the simplest truths, weighing how a single word might provoke an authoritarian power.

Just in the same month as the NPM exhibition opened in Prague, an art exhibition supported by Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and featuring eight Taiwanese artists at the Central State Museum in Almaty, Kazakhstan, was abruptly cancelled at the last minute. According to Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the exhibition’s main visual prominently featured the title “Taiwan Contemporary Art Exhibition,” which led to pressure and interference from China on the museum.

This kind of disgraceful pressure from China on Taiwan’s cultural events in other countries is a routine feature of Taiwan’s diplomatic reality. Whether cultural institutions can withstand such interference often depends on their own resilience and circumstances. Last year, the Avignon Off Festival in France also came under pressure from Beijing, which demanded that Taiwan be removed as the festival’s “featured country.” The organisers insisted on the festival’s independence, autonomy, and diversity. They refused to accept violence and threats. One installation — The Faces of Taiwan, a wall of portraits — became a quiet symbol of that decision. China’s consul-general reportedly refused to walk past it.

The tactics of pressure may vary, but the impact is similar: doubt creeps in, self-censorship takes hold, and democratic cultural spaces become narrower without anyone quite noticing. Yet these different cases also show that outcomes are not predetermined — and that institutional courage still matters. A word left out, an identity softened, a narrative trimmed at the edges — these are not minor edits. They reveal how external pressure seeps into the fabric of democratic institutions, normalising caution where openness should prevail.

Cultural spaces do not shrink overnight. They contract through a series of seemingly “practical” adjustments, decisions rationalised as harmless or neutral. But these quiet concessions accumulate. And that is how chilling effects take root — not through explicit bans, but through the gradual erosion of confidence in telling the truth.

Democracies must not outsource their cultural autonomy

The silence surrounding Taiwan in Prague may seem like a minor curatorial choice. But details accumulate, and silence has a price. Once cultural institutions learn that avoiding offence is safer than standing by fact, it is not Taiwan that loses first — it is the integrity of democratic public space. What disappears next may not be a country’s name, but the confidence of institutions to speak truthfully at all.

Cultural exchange is meant to expand understanding, not contract it. Democracies cannot defend their values if they begin to treat them as negotiable, or as something that can be trimmed away whenever an external actor objects. When truth becomes contingent on geopolitical convenience, cultural institutions risk becoming vehicles for someone else’s narrative.

Increasingly, Beijing is setting its red lines not just within its own borders, but across global cultural industries and even in people’s minds. From blocking exhibitions and cultural exchanges, to pressuring singers and actors to publicly demonstrate loyalty to the regime and conform to its One-China Policy narrative, the goal is the same: to make the world internalise the limits of what China deems acceptable. The danger for democracies is not only that these red lines are enforced, but that they begin to be anticipated and obeyed — without ever being stated.

The exhibition in Prague should have been a celebration of shared heritage. Instead, it became a reminder of how fragile cultural autonomy can be when confronted with authoritarian pressure, and how easily that pressure can be internalised long before it becomes visible to the public.

This is not simply a story about Taiwan. It is about whether democratic societies can still tell the truth — openly, confidently, without fear or calculation. The question is not abstract: if democracies cannot uphold factual clarity in museums, the very spaces tasked with preserving cultural memory, where can they? We talk a great deal about social resilience as the backbone of democratic defence, yet whether our “cultural resilience” is strong enough remains strikingly underrepresented in public debate.

When cultural exchange meets authoritarian red lines, democracies must decide whether to retreat into silence or reaffirm what makes them democratic in the first place. The future of cultural freedom — and of truth itself — depends on that choice.

Isis M. Lee currently serves as Advisor and is the former Vice President of Radio Taiwan International (Rti), Taiwan’s international public broadcaster. With a career that spans cultural policy, international cultural exchange, content curation, and public media governance, Isis has worked extensively on media resilience, cross-cultural innovation, and international collaboration to amplify Taiwan’s global voice. Before entering the media sector, Isis was active in Taiwan’s cultural heritage industry as a manager and curator. She also served as Deputy Secretary General of the Taiwan Association for Cultural Policy Studies and as Director of the Global Outreach Office at the Ministry of Culture.