Written by Timothy S. Rich and Madelynn Einhorn.

Image credit: Immigration by Nicola Romagna/Flickr, license CC BY 2.0

Taiwan’s 2020 election was its first with immigration as a salient issue. The country’s immigration challenges are not unlike those in other developed nations, where the demand for immigrant workers faces a domestic backlash. Meanwhile, immigrant workers, predominantly from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, increasingly have been more vocal about concerns of unfair treatment, including protesting labour conditions and the broker system for employment.

Taiwan’s immigration policy remains poorly equipped to meet current demands and scholarly research on Taiwan’s immigration remains underdeveloped (see examples here and here). Likewise, Taiwan still lacks a refugee law, with the Refugee Act languishing for over ten years over concerns about how to handle Chinese refugees. In addition, until recently political parties had little incentive to recruit immigrants or even reach out to naturalised immigrants. The KMT’s Lin Li-Chan of Cambodian descent was in 2016 the first immigrant legislator elected.

According to immigration data from the Ministry of the Interior, as of October of 2019, 794,974 immigrants reside in Taiwan. Those from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines comprised 81.9% of Taiwan’s immigrant population, and saw a 67.4% increase from October of 2013, compared to an overall immigrant population increase of 55.5%. However, the number of new immigrants to Taiwan is declining as less immigrants marry Taiwanese nationals. Taiwan is struggling particularly to attract high-skilled immigrants, which are needed to counter Taiwan’s low birth rates and aging population, and recently ranked the third worst country at recruiting the highly skilled professionals. Meanwhile, reports of Taiwanese welcoming Southeast Asian immigrant in particular still tend to focus on skilled arrivals. For example, Taiwan Business Topics interviewed immigrants who believe that the Taiwanese are becoming more welcoming to immigrants, but the immigrants interviewed were both highly-skilled: a Filipino woman who teaches English and a Vietnamese man who works in the computer science industry.

The Taiwanese government has discussed or implemented several policies designed to encourage immigration. In 2018, Taiwan drafted a bill allowing foreign students who completed high school or vocational degrees in Taiwan to remain in the country to meet increasing demand for medium-skilled workers. More recently, The New Economic Immigration Act incentivises skilled workers to come to Taiwan to fill the need for high-skilled workers.

Concerns about immigration typically focus on market competition with domestic workers, the economic costs of immigration, criminality, and abilities of immigrants to assimilate to cultural norms. For example, critics are concerned with the costs associated with extending access to the National Health Insurance (NHI) to pregnant immigrants. In addition, skilled immigrants are viewed as more desirable, yet most attention falls on unskilled immigrants, with parties and the media often highlighting the negative attributes of unskilled immigrants based on nationality, which can further erode public support.

KMT presidential candidate Han Kuo-yu in March questioned whether the Taiwanese public would accept skilled labour from the Philippines, using the derogatory term “Marias” commonly associated with Filipina domestic workers. In August, Han again addressed immigration, referring to recent migrant labourers compared to Taiwanese brain drain as “phoenixes flying away and a bunch of chickens coming in!“. In response, President Tsai Ing-wen publicly stated that elected officials should not use “erroneous and stereotypical statements to single out immigrants and migrants,” who come to Taiwan. Tsai’s immigration agenda has also focused on improving social welfare for migrants and increasing language classes in public schools.

Considering the broad literature on how framing and priming influences public opinion, and the growing literature specifically on these effects in Taiwan (e.g. refugees, same sex marriage, and diplomatic recognition), we employed an experimental survey to address immigration. Specifically, we wanted to evaluate to what extent public opinions on immigration were influenced by two factors: the skills of immigrants and their place of origin.

Previous work on Taiwan finds a clear bias against Southeast Asian immigration, with support for immigration declining 21-31% when the focus shifted from immigration in general to Southeast Asian immigration specifically. However, it remains unclear whether the public differentiates among the three largest Southeast Asian immigrant populations: Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. For example, the gender balance of the immigrant population potentially influences public perceptions. Females comprise 53.8% of the total immigrant population according to October 2019 data. Of the three countries in question, this ranges from 40.6% for Vietnamese immigrants to 60.3% and 73.4% for the Filipino and Indonesian immigrants.

Workers from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines are typically factory or domestic workers. Taiwan’s work visa options have also varied by country as well. For instance, from 2005 to 2015, the Taiwanese government stopped handing out work visas to Vietnamese fisherman, caregivers, and domestic workers, a policy that likely encouraged the recruitment of workers elsewhere in the region. In 2019, a new hiring policy was implemented encouraging employers to hire Indonesian workers directly instead of through brokers. However, Vietnamese and Filipino immigrants still must use the heavily critiqued brokerage system to find jobs in Taiwan. In the same year, Indonesia stopped sending students to internship-study programs at Taiwanese universities after allegations that Indonesian students were forced to work in factories.

In order to disaggregate views of immigration by skill and country of origin, we conducted an experimental web survey through PollcracyLab at National Chengchi University’s (NCCU) Election Study Center in December. Five hundred and two respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of eight versions of a statement and asked to evaluate the statement on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The versions were:

Version 1: Taiwan should encourage immigration

Version 2: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers

Version 3: Taiwan should encourage immigration from Vietnam

Version 4: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers from Vietnam

Version 5: Taiwan should encourage immigration from the Philippines

Version 6: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers from the Philippines

Version 7: Taiwan should encourage immigration from Indonesia

Version 8: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers from Indonesia

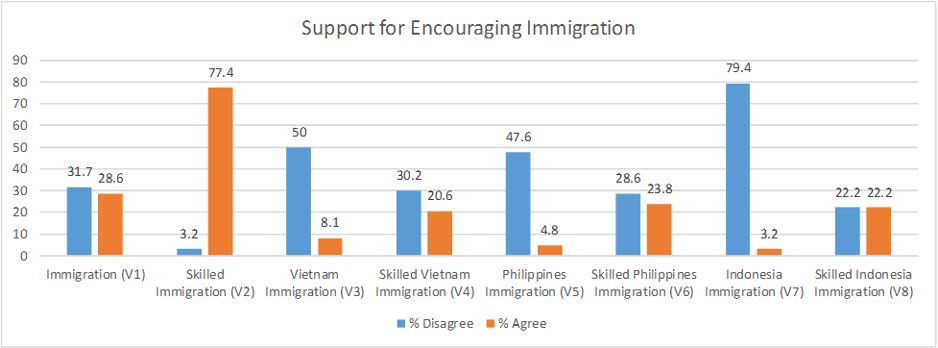

The figure below shows the percentage of respondents that disagreed or agreed with each version. Several patterns emerged.

Overall, the results are consistent with past surveys which find that Taiwanese people perceive skilled immigrants more positively than immigrants in general. However, the bump in support between versions that mention skilled immigration versus no mention of skills is worth noting. When no country of origin is mentioned, support for immigration increases by 48.8% when framed as skilled immigration. Yet, the boost in support for skilled immigration from the three Southeast Asian countries assessed is noticeably smaller (Vietnam 12.5%, Philippines and Indonesia 19%). Moreover, we see clear variation in public perceptions across the three Southeast Asian immigrant groups. First, in versions that do not mention skills, the public was far less supportive of Indonesian immigration, with 79.4% disagreeing with encouraging immigration, compared to 50% for Vietnam and 47.6% for the Philippines. When the focus shifts to skills, a majority of respondents answered ambivalently, neither agreeing nor disagreeing with encouraging immigration, compared to only 19.4% of respondents when no reference to skilled immigrants’ country of origin was presented.

A potential indirect cause of the differences could be the different legal routes for Southeast Asian immigration to Taiwan, with Indonesians having a more direct route to work in Taiwan than Vietnamese and Filipino workers. Admittedly, it is unlikely that the public is aware of these distinctions, but rather are responding to the outcome of an influx of Indonesian immigrants. Our findings further suggest the importance of disaggregating the countries of origin when we talk about immigration.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics in East Asian democracies.

Madelynn Einhorn is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Political Science and Economics.