Written by Kristina Kironska

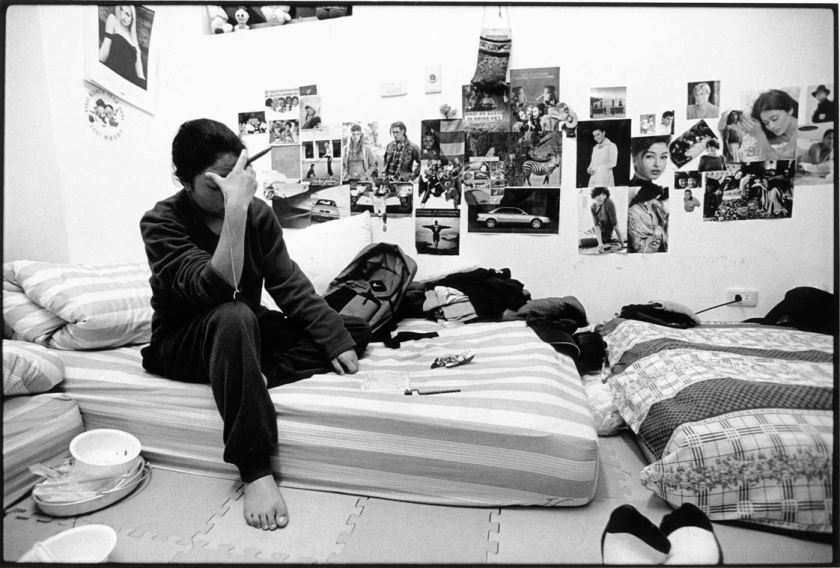

Image credit: 西藏難民 確揚-漂泊的人生 by 楊永智/數位島嶼, license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Taiwan is considered one of the most progressive countries in Asia but has no asylum law. Although debates on the issue occasionally occurred for more than ten years, there has been no progress on the draft asylum law since its second reading in 2016. One significant point of contention is to what extent an asylum law should address not only people from “uncontroversial” foreign countries, such as the Rohingya in Bangladesh, but also people from China, Hong Kong, and Macau. As with any issue that touches on cross-strait relations, the situation is complicated: on the one hand, the government celebrates Taiwan’s status as a beacon of human rights; on the other, extending asylum to PRC citizens risks stoking tensions with Beijing.

Due to the political status of Taiwan, the challenges it faces are quite different from other countries. Because the ROC was replaced in the UN China seat by the PRC, Taiwan has not signed up to UN treaties for handling asylum seekers and refugees. Nevertheless, Taiwan has accepted five international human rights treaties. Among them, in 2009, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (which binds its signatories to respect civil and political rights, such as the rights to life, freedom of religion or speech), which introduced the non-refoulment obligation in Taiwan.

Taiwan cannot ignore the refugee issue because various groups of people require protection, and the government cannot respond effectively in the absence of asylum law. Taiwan receives asylum seekers (both self-identified and those already recognised by the UNHCR) every year. However, the authorities are unclear regarding how these cases will be processed, with each authority claiming it is not their responsibility. Immigration only considers how to grant foreigners the right to stay in a country, but refugees require much more than that. Currently, applications are handled on a case-by-case basis with very different outcomes. With such a system, most asylum seeker cases have relied on civil society groups (such as the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, TAHR), which depend on their own resources to provide accommodation, medical treatment, or psychological counselling. While some people have managed to receive some sort of support (such as visa extensions or negotiations with third countries) and stay temporarily in Taiwan, others have been deported without taking into consideration the risk of harm if they are returned to their place of origin (despite the binding non-refoulment obligation mentioned above).

This does not mean Taiwan has never accepted anyone. A few examples from the past include in the early 1960s, during large-scale ethnic tensions between Indonesian Chinese and indigenous people in Indonesia when Taiwan sent two warships to receive those ethnic Chinese who wanted to leave; admitting some 6,000 Vietnamese refugees during the 14 years from 1976 to 1990 and placing them in refugee camps on Penghu islands (at the time, the camps were still under martial law, so they were managed by the army) in the Rende Project and accepting more than 2,000 refugees from the Indochina region floating in the South China Sea in the Haipiao Project. Many of the people Taiwan accepted under these projects were Overseas Chinese and were eventually allowed to settle in the country.

Political rivalry between the PRC and ROC led to the creation of the specific immigrant category for Overseas Chinese, based on the patriarchal jus sanguinis principle, which remains in place to this day. Overseas Chinese who can prove that they or their parents have at one point held an ROC passport can register for the Overseas Chinese Certificate and with that, apply for settlement in Taiwan – between 1982 and 2007, a total of 230,999 such people settled in the ROC.

Taiwan is active also with regard to providing financial help to refugees abroad. The country is part of many development projects around the world aimed at meeting the urgent needs of those impacted by regional turmoil. For example, Taiwan has provided over US$20 million in humanitarian assistance programs since the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011. There is also an agreement with Australia to provide medical treatment for refugees and asylum seekers in Nauru (bringing them to Taiwan for surgery if necessary). However, the MoU is confidential, so there is not much known about the agreement’s content or the number of people flown to Taiwan.

In the past, there were a few attempts to enact an asylum law. A draft law (inclusive of Chinese nationals) was first sent to the Parliament in 2005 with the aim “to safeguard the status of refugees, to protect the rights and benefits of refugees, and to encourage international cooperation on matters related to human rights,” but it has not been discussed any further. Similarly, in 2011 and 2012, draft laws were submitted and discussed in public hearings but never picked up by any parliamentary committee for further discussion. The Minister of Interior objected that there were not enough experts to handle this issue, and Taiwan needed more supplementary laws to facilitate an asylum law. At the end of the parliamentary term (under the KMT) in January 2016, all draft laws, including the draft asylum law, were removed, and erased.

In 2016, with the start of the new parliamentary term (under the Democratic Progress Party, DPP), four versions of the draft law were submitted by (1) Yu Mei- Nu (DPP) and Apollo Chen (KMT), (2) Hsiao Bi-khim (DPP), (3) Tsai Yi-yu (DPP), and (4) the Executive Yuan. All of these draft versions excluded Chinese nationals. By that time, there was a consensus that it would be easier (politically) to pass such a version of an asylum law, and PRC nationals would be dealt with later. The draft passed the first reading under the Committee of Internal Administration but was subsequently not sent through to the second and third readings. When the parliamentary term (under the DPP) ended in January 2020, again, all the discussed laws were erased.

Currently, there is a new draft law submitted to the parliament; however, its contents have not yet been publicised, nor discussed in the parliament. There is not enough political will to push an asylum law through. Moreover, there are still many questions lingering over the definition of a refugee and limits on numbers, as well as their rights and obligations. Nevertheless, adopting an asylum law is part of a broader push to bring Taiwan’s legal system in line with international human rights law, and should not be ignored.

The full version of this article has been published under the title Taiwan’s Road to an Asylum Law: Who, When, How, and Why Not Yet? in Human Rights Review, 2022. Link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12142-021-00644-y

Kristina Kironska is a socially engaged interdisciplinary academic with experience in Myanmar Studies, Taiwan Affairs, CEE-China Relations, human rights, election observation, and advocacy. Currently, she is conducting research within the Sinophone Borderlands project administered by the Palacky University Olomouc. She is also the Advocacy Director at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies. She can be reached at k.kironska@gmail.com.

This article is published as part of a special issue on European Association of Taiwan Studies.

One comment