Written by Zuzule Demalalade & Tien-Li Schneider.

Image credit: Sharing the Paiwan Hand Tattoo Culture at the Artist Studio, Burke Museum. Photo courtesy of Tien-Li Schneider, Hand Tattoo Workshop Coordinator.

When we believe that there is power behind every object, it signifies our departure from mundane perspectives and a return to the cosmic space we share with our ancestors.

As Indigenous cultural curators based in Taiwan, our involvement with the Kuroshio Odyssey: Maritime Memories, Culture, and Landscapes (hereafter KO) exhibition project began on an ordinary workday when KO’s curator, Jiun-Yu, returned from the United States to Taiwan and visited our office one afternoon. He mentioned that the Burke Museum had some collections from Taiwan’s Indigenous tribes. Together with Nikal (Margaret), a law doctoral student at the University of Washington with Amis Indigenous roots in Taiwan, they were planning an exhibition on Taiwanese Indigenous artefacts. This sparks the idea of collaboratively establishing an online platform, a digital bridge across the 14-hour time difference between Taiwan’s Indigenous artefacts and the Burke Museum’s exhibits.

We found this digital collaboration to be a profoundly meaningful endeavour. The significance lies not only in the opportunity to showcase the Burke Museum’s Taiwanese Indigenous collections to the public but also in allowing these century-old objects to narrate their own stories and resonate with similar collections in Taiwan. Each artefact narrates its own story, from the craftsmanship of making to its usage, while weaving a connection with its tribal cultural origins. The objects revive people’s memories of them through exhibitions, thereby demonstrating the profound influence that objects hold. Indeed, objects possess power.

In deciding to join the KO exhibition project, our team in Taiwan were responsible for selecting artefacts from our collection that could engage in a dialogue with those displayed at the Burke Museum. For instance, as the Burke Museum showcased a beadwork garment from an Atayal tribe, we paired it with a beadwork vest from the same tribe. Another remarkable item at KO was a nose flute crafted by the late and highly respected Paiwan elder, Mr Pairang Pavavaljung, who passed away in 2023. This exquisitely carved nose flute featured traditional Paiwan motifs. In our museum at the Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park in Pingtung, Taiwan, we hold a mouth flute made by Mr. Pavavalung’s son, Etan Pavavaljung, an accomplished Paiwan artist. We intentionally paired the son’s mouth flute with the father’s nose flute, bridging time and distance and allowing their works to meet in the cloud. Here again, we see the power of objects.

For the KO online exhibition, we selected a total of 24 items from our collections in Taiwan. In addition to facilitating online interactions between these items and the Burke Museum’s collections, curator Jiun-Yu suggested selecting a few everyday objects to enhance the exhibition’s “living” atmosphere. Thus, we chose several utensils commonly used by various Indigenous tribes in their daily lives. For instance, the SaySiyat wooden steamer is characterised by its tubular form and steam holes connecting the upper and lower sections. The upper part, lined with woven rattan to hold food, faces upward, while the lower part stands downward into steaming water. The wooden steamer is paired with a lid, ensuring thorough food steaming. Crafted from a single Chinese parasol tree trunk, the steamer was commonly used by both SaySiyat and Atayal tribes, who traditionally preferred non-pottery cooking utensils.

In addition, we selected a coconut shell water-fetching vessel adorned with woven rattan, commonly used by the Yami (Tao) people of Lanyu (Orchid Island), situated to the south of Taiwan. This tool was multifunctional, utilised both for drinking water from mountain springs and streams and collecting seawater for cooking, primarily for fish soup.

Photo credit: Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Center.

This coconut shell water-fetching vessel made a deep impression on me when a Yami (Tao) girl in her twenties shared with us her story of such a tool. She recounted that when she was a child, during dinner preparations each evening, her mother would send her to the beach with a coconut shell to fetch seawater. The seawater she brought back was added to the soup of freshly caught fish that completes a delicious family dinner every night. This anecdote not only revived memories for her but also prompted those outside the Yami (Tao) community to reflect on the cultural and emotional weight of the coconut shell vessel in our collection. Engaging with this artefact, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have reestablished connections to the coconut shell and, by extension, to each other. This is the resonant power of objects.

In the inaugural week of the KO Exhibition, we presented two cultural workshops in the Artist Studio to our visitors at the Burke Museum—the Paiwan hand tattoo experience and the Paiwan and Rukai Glass Beadwork activity. Traditional tattoo practice was abolished during the Japanese colonial period. Hand tattoos, for the Paiwan women, were symbols of identity because the motifs tell the person’s family background and status. This tradition, almost lost over time, was revitalised in recent years. As a descendant of the Paiwan people, receiving hand tattoos with motifs of my grandmother was like reconnecting myself with my family, identity, and heritage. We hope that through our hand tattoo session, our KO participants will understand the significance of our tattoo culture.

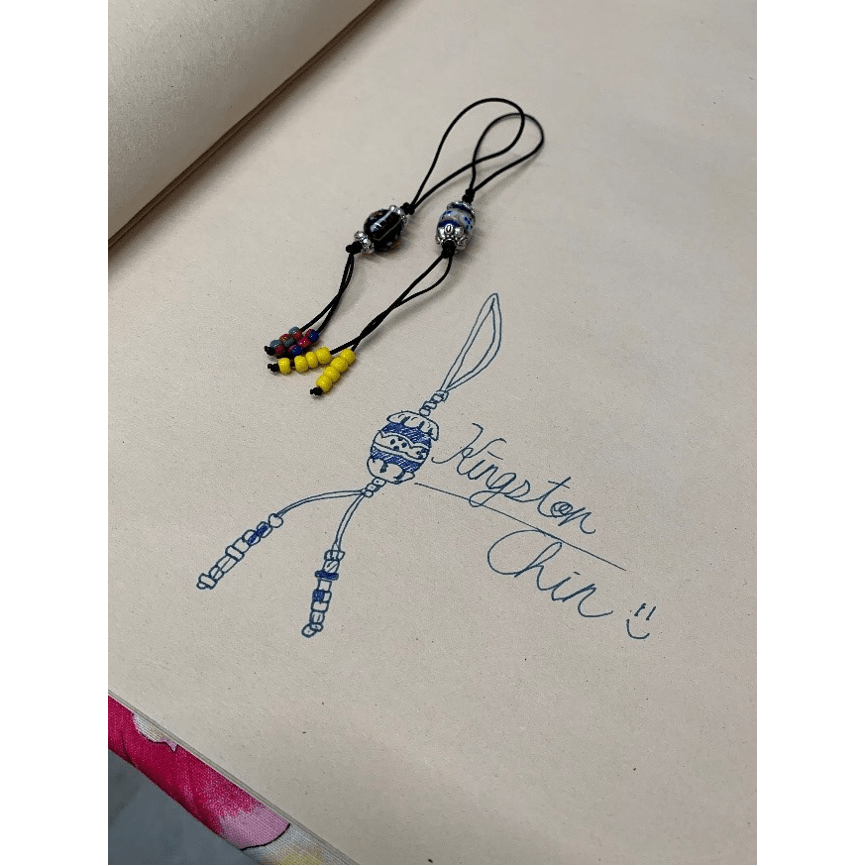

According to our lore, glass beads are blessings from heaven and ancestors. For the Paiwan and Rukai people, glass beads hold great significance and symbolise beauty and social status. While the skill of making the beads was once lost, the tradition of wearing them has endured on until today. In fact, the beads are being made into a variety of contemporary accessories and decorations. For instance, during the beading workshop, the participants made key hangers and bracelets. Although the cultural meaning of beads may not resonate with our participants, however, the experience still inspired them to appreciate and learn more about Paiwan and Rukai’s aesthetic and traditional culture. It was encouraging for us to observe the talented participants, as demonstrated by the following image, who not only mastered the craft of beading but also captured the details of Paiwan’s beadwork in their drawings.

Photo credit: Tien-Li Schneider, beading workshop coordinator.

It has been an honour and pleasure for us to be part of the Kuroshio Odyssey journey. Collaborating with the enthusiastic team at the Burke Museum—including curators Jiun-Yu, Nikal, Holly Barker, and Sven Haakanson, collections managers Dominique, and assistants Gabbie and Emma—has been a deeply enriching experience. This journey has been mind-filling as we learned so much from each other. We hope that our online exhibit and culture workshops have inspired the people of Seattle to learn more about our beautiful Taiwanese Indigenous culture as much as our objects have inspired us.

Zuzule Demalalade is Paiwan, a Taiwan indigenous, and is currently working at the Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Center, Council of Indigenous Peoples in the Department of Culture Promotion. She is responsible for the museum in the Center and has curated exhibitions on Taiwan’s indigenous culture, artefacts, and the revitalising of traditional indigenous handicrafts.

Tien-Li Schneider (Lili) is an accountant who was born in Taiwan and raised in New Zealand. Growing up in a multicultural country, Lili has a passion for learning about different cultures. She joined the Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Center in 2019 and participated in the curating of an exhibition on Taiwan’s indigenous culture at the National Belau Museum in Palau. Since then, she has assisted in curating indigenous-themed exhibitions, organising indigenous craft workshops, and giving lessons on indigenous culture to non-indigenous people.

This article was published as part of a special issue on Kuroshio Odyssey Part II: Insights from Indigenous Collaborators.