Written by Yu-Chen Chuang.

Image credit: public domain.

2023 was a frustrating year, particularly for those advocating for Taiwanese Indigenous peoples’ rights and the progression of decolonization. Since the beginning of the year, discriminatory events against Indigenous peoples have frequently surfaced in the media. Accompanying these news events, unfortunately, is an increase in hateful and unbearable discriminatory language abuses across online platforms. An example of these discriminatory incidents happened in the “Free Speech Month” held at the National Taiwan University (NTU), one of the most prestigious universities in Taiwan, in May 2023. During the event, a student hung a banner on campus, expressing their upset with the current policy that grants Indigenous students an extra 35 per cent in school admission exams. In a form submitted to the Student Association organizing the event, the student described their intention behind the banner as “The privilege given to Indigenous peoples is the government’s tyranny against the non-Indigenous.”

In fact, the current policy guaranteeing educational opportunities for Indigenous students does not infringe upon the admission slots allocated to non-Indigenous students. People narrowly focus on “equal” resource allocation to criticize the current welfare measures for Indigenous students. Yet, they overlook the ongoing harms and negative impacts of historical colonial oppression. This anger towards Indigenous students exposes a deeper systematic issue within Taiwan’s education system. On the one hand, the education system established by settlers has led to the long-term loss of the Indigenous people’s languages and cultures. On the other hand, it is critical to recognize that many educational and research resources have been developed at the cost of Indigenous peoples’ heritage and sovereignty, often involving the dispossession of their lands, cultural artefacts, and even skull remains.

2023 was also a crucial year for universities, as education and research institutions, to re-examine their role in perpetuating historical injustices. Some universities began reassessing their relationship with Indigenous peoples in Taiwan. They have long benefited from and possibly reinforced the inequalities rooted in settler colonial structures. With discriminatory attacks against Indigenous peoples intensifying both online and in the real world, it’s imperative to envision an education system that not only acknowledges but actively addresses the wounds of settler colonialism.

A Historic Gesture of Repatriation

In November 2023, following four years of discussions and negotiations with Taiwanese Indigenous peoples and governmental representatives, the University of Edinburgh repatriated the skulls of four tribal warriors to an Indigenous Paiwan community. This act marked the first instance of such international repatriation for Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples. The repatriation of these remains involved a series of historical investigations, representing a significant opportunity for the Paiwan community to reconnect with their ancestors’ history. Moreover, it facilitated an equitable negotiation between the Indigenous peoples, the government, and the university, through which the Indigenous community could realize their rights and heal from historical wounds.

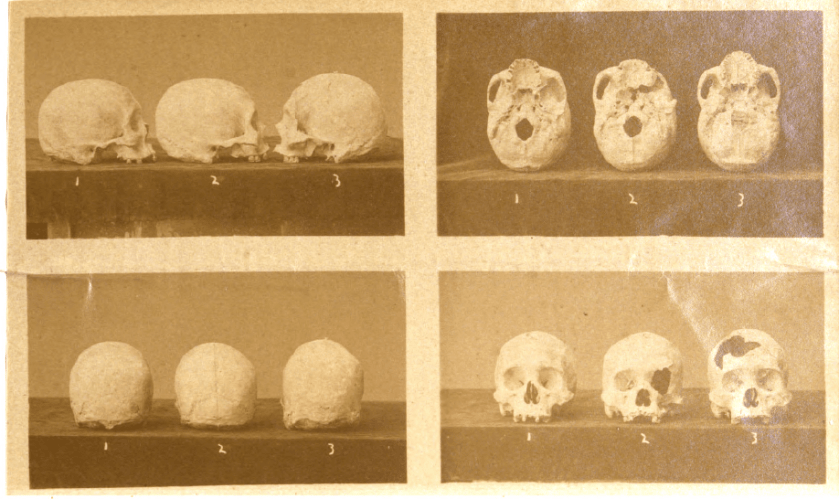

Why were these ancestral remains of Taiwanese Indigenous peoples kept at the University of Edinburgh, nearly ten thousand kilometres away in the United Kingdom? The answer traces back to colonial expeditions and academic pursuits spanned two continents. The ancestral remains were taken by Japanese soldiers as war trophies in 1874. Subsequently, William Turner, an anatomist and then-Principal of the University of Edinburgh, acquired four of these skulls for his collection and research in 1907. At the time, these skulls became William Turner’s data for his craniology research.

Craniology, once popular in the United States and Europe in the 19th century, is a pseudoscientific theory of skull characteristics. The field supported the rise of scientific racism at the time, which suggested racial inferiority based on skull shape and size. This case highlights the unjust relationship between Indigenous peoples and research institutions: the latter appropriated Indigenous remains and artefacts for research purposes yet used them to produce racist theories that further entrenched the inequalities.

The repatriation of remains in 2023 marked a significant step for research institutions to reflect on their roles in the historical legacy of colonialism. In November, the Paiwan people arrived at the University of Edinburgh. Dressed in traditional attire, they conducted a ceremony to guide their ancestors’ remains and spirits back home. Upon returning to Taiwan, the community also collaborated with museums to arrange the future preservation of these remains.

Decolonization in research institutions remains a long and ongoing journey. In parallel, NTU faced its own challenge with the Kunuan tribe, an Indigenous Bunun community, regarding similar issues of ancestral remains. Last November, a heated conflict erupted between them when the Kunuan people petitioned for repatriation. This conflict dates back to the 1960s when NTU’s Medical College excavated an Indigenous cemetery and took the remains of their ancestors without consent for the sake of physical anthropology research. It wasn’t until 2012 that a student advocating for Indigenous rights uncovered this unjust history. This ongoing controversy between NTU and the Kunuan people underscores the imperative need for meaningful dialogue on the university’s responsibility for historical injustices.

The Continuing Dialogues

NTU and the Kunuan people haven’t reached a consensus until now. After all, repatriation is not just a simple “return.” The negotiations also involve formal apologies, compensation, and planning for future preservation. While dialogues are ongoing, this dispute that erupted in 2023 is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how Taiwan’s research institutions have infringed upon Indigenous rights throughout their academic development.

Here’s another example that brings historical perspective into focus. Since the early 1900s, under Japanese rule, Taiwan’s forests were identified as valuable for research, leading to the creation of ‘experimental forests.’ Prominent Japanese imperial universities at the time were involved in their establishment. These experimental forests, which frequently overlapped with lands traditionally used by Indigenous peoples for hunting, farming, and living, led to the gradual exclusion of these communities.

After WWII, the Republic of China’s government took over the control of these forests. They are currently managed by governmental entities, such as the Forestry Research Institute, or serve as university experiment forests. Notably, National Chung Hsing University and National Taiwan University, leaders in forestry and agricultural research in Taiwan, possess extensive forest lands that are crucial for their research and teaching. Despite their significant role in research and education, these government and university-managed experimental forests remain a point of contention with Indigenous communities.

In light of such colonial history and the rampant discrimination issues, NTU established an Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Equity Working Group in 2023. This initiative is a significant step in recognizing and actively addressing Indigenous issues within the campus. The Working Group’s objectivity extends beyond improving students’ comprehension of Indigenous and ethnic equity and fostering a more inclusive campus environment. It also seeks to initiate a deeper reflection on NTU’s historical role since the colonial era. This includes understanding the history of lands the university possesses, examining its interactions with Indigenous communities, and actively developing and advocating for their Land Acknowledgement.

As we enter 2024, Taiwan continues to grapple with numerous incidents of discrimination against Indigenous peoples. This article highlights the important role of academic institutes in addressing the pervasive and rooted discrimination in Taiwanese society. Academic institutes should take action to reflect on their privileged role in the settler colonial structure, facilitate meaningful conversations and equitable interactions with Indigenous communities, and actively work to redress their long-term uneven power relations with these communities. These actions rely on continuous institutional and educational reforms, alongside more ethical research initiatives collaborating with Indigenous peoples. The goal is not only to uncover past injustices but also to build paths toward a future of reconciliation.

Yu-Chen Chuang is a PhD student in Geography at Penn State University. Her research interests lie at the intersection of political ecology, critical Indigenous studies, and science and technology studies, focusing on the intertwining relationship between environmental governance and settler colonialism in Taiwan. Yu-Chen also serves as an editor of Taiwan Insight.

This article was published as part of a special issue on “2023 to 2024: Looking Back, Thinking Ahead.”