Written by Mark G. Murphy.

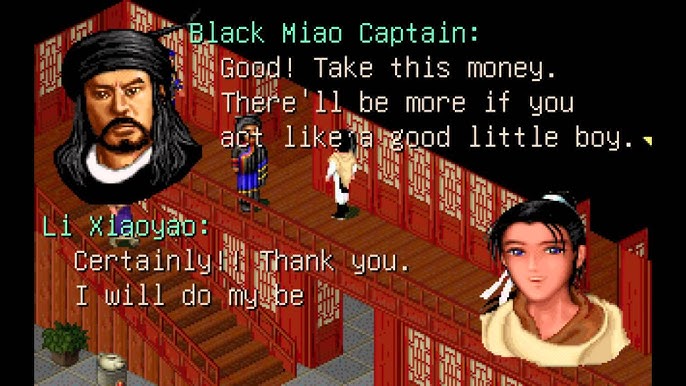

Image credit: screenshot of The Legend of Sword and Fairy by Softstar Studio.

The article will be published in two parts, with the first part presented here. The second part will be available on the 20th of November.

Recent years have seen a surge in video games drawing from global mythological traditions, reimagining ancient stories for contemporary audiences. God of War Ragnarök masterfully weaves Norse cosmology with Greek mythological elements, while Elden Ring builds its dark fantasy world on Celtic foundations, particularly Welsh and Irish mythology. The critical and commercial success of these games demonstrates how mythological storytelling can create rich, resonant worlds that bridge cultural traditions with modern gaming experiences.

But today, a game that has been a surprising and refreshing hit is Wukong: Black Myth. This is an action RPG developed by Chinese indie game studio Game Science, inspired by the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West. The game reimagines the character Sun Wukong, the legendary Monkey King, known for his shape-shifting abilities, immense strength, and intelligence and his struggle against the powers of heaven.

Players take on the role of Wukong as a trickster archetype battling mythological creatures and uncovering mysteries in a lush, highly detailed world that blends Chinese folklore with stunning, modern graphics.

The team behind Black Myth: Wukong at Game Science mentioned in a recent interview that they view the game’s success as “a gift from our ancestors.” This reflects their appreciation for the timeless storylines and characters adapted from the classic Journey to the West, originally written during China’s Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

The game and its wuxia mythology itself are being used as a form of Chinese Soft Power. As Tim Brinkhoff states,

‘As far as soft power is concerned, narrative-driven games also offer greater opportunities for storytelling based on Chinese culture and history. The Wind Rises in Luoyang, a forthcoming Dark Souls-inspired action-adventure game developed by Keyframe Studio, is set in the era of the Tang Dynasty during the reign of Empress Wu Zhao (690-705 CE). In Three Kingdoms Zhao Yun, a strategy game by Zuijiangyue Game, players assume the role of a real-life military general during the late Han dynasty. “Journey to the West,” the source material of Black Myth: Wukong, is perhaps the single most influential text in all of Chinese literature. Sun Wukong, in particular, has evolved into a transcultural archetype, inspiring a variety of modern-day action heroes, from Japan’s Son Goku (“Dragon Ball Z”) and Monkey D. Luffy (“One Piece”) to America’s Aang (“Avatar: The Last Airbender”). “’

China’s emphasis on game development rooted in mythology often overlooks Taiwan’s unique contributions, particularly how Taiwan has used wuxia themes in media to inspire imagination. As the heroic-cinema site explains, modern wuxia games draw deeply from a long history of wuxia literature, adapting themes from Chuanqi tales of the Tang dynasty and huaben stories of the Song dynasty, which introduced elements like martial heroism, supernatural events, and vengeance. Ming and Qing dynasty classics, such as The Water Margin, solidified the genre with stories that subtly criticised authority and portrayed the xia (hero) as a figure of honour and defiance.

The May Fourth Movement in 1919 reshaped wuxia, challenging Confucian norms and portraying heroes who symbolised independence and rebellion. Authors like Huanzhu Louzhu and Wang Dulu then evolved the genre further by adding emotional depth, secret societies, and moral complexities, leading to distinct ‘Northern’ and ‘Southern’ schools. The Northern school, rooted in Beijing, adhered to a historical, realist approach, while the Shanghai-based Southern school embraced newer literary influences.

Today’s wuxia games inherit these traditions by blending heroism with a grounded sense of place and cultural identity, inviting players into stories where loyalty, sacrifice, and moral ambiguity are central. This legacy of connecting myth to real-world struggles and landscapes keeps wuxia stories relevant, giving players an experience that bridges the personal and the mythic. Notably, during turbulent times, such mythology has served not merely as escapism but as a means of connecting individuals to a narrative that strengthens confidence on both personal and communal levels. Traditional martial arts practices in Taiwan often embody this connection, as they involve adopting a story through the ‘forms’ practised—a combination of movement, narrative, and intent. In this way, the act of play becomes a source of personal and collective empowerment.

In the mid-1990s, Taiwan saw significant growth in its gaming development scene, with local studios concentrating largely on PC-based RPG-Wuxia games, and strategy titles. One of the most notable successes was The Legend of Sword and Fairy (仙剑奇侠传) (also known as Chinese Paladin), created by Softstar Entertainment in 1995. This game achieved massive popularity across Taiwan, mainland China, and other Chinese-speaking regions due to its unique mix of fantasy, mythology, and wuxia themes.

Taking a pioneering role in Chinese-language RPGs, The Legend of Sword and Fairy emerged from an elaborate world steeped in traditional Chinese lore. The game masterfully wove together martial arts, spiritual themes, and mythological elements in ways that deeply resonated with audiences. Its influence reached far beyond Taiwan’s borders, establishing a distinctive Chinese storytelling approach within the RPG genre that would inspire countless games, TV series adaptations, and spinoff media in the decades that followed. The game’s success demonstrated the power of cultural authenticity – at a time when Chinese gaming culture was still in its early stages, Taiwanese studios proved they could create experiences that were both deeply rooted in tradition and commercially viable across Chinese-speaking markets.

In the second part of this article, I will examine how rootedness proves essential to cultivation (a cornerstone of wuxia philosophy), moving beyond its role as a narrative device to reveal how it enables deep mythological and creative connections to one’s environment – connections that form the true foundation of soft power.

Mark Gerard Murphy is an academic and lecturer in theology and philosophy and also a practitioner of martial arts. He is the author of several academic books and articles.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Gaming Taiwan’.