Written by Li-Ting Chang.

Image credit: “Typeset Hopes and Dreams: Exhibition on Contemporary Czech Literature,” National Museum of Taiwan Literature by EJ Chiu.

In recent years, the Czech Republic has become one of Taiwan’s closest European partners, with frequent exchanges taking place not only in the fields of politics and economics but also in arts and culture. These exchanges are particularly valuable and promising due to their similar positions in confronting hegemonic geopolitical power in the contemporary world and their parallel histories of political oppression. The year 2024 saw exciting activities that stimulated and advanced Czech and Taiwanese literary writing, publication, and translation. Two Taiwanese authors, Hsieh Kai-te (謝凱特) and Shieh Zi-fan (謝子凡), participated in the Book World Prague 2024 literary festival for the translations of their works, My Ant Father (我的蟻人父親) and I and the Garbage Truck I Chased (我和我追逐的垃圾車), in the Czech language. On the first day of July 2024, Authors’ Reading Month (ARM) welcomed 31 Taiwanese writers from different generations to share their literary works in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ARM, an influential annual literary festival in Central Europe, chose Taiwan as its guest of honour in 2024 to introduce its literature and literary culture by hosting talks for each writer and inviting them to read their works aloud in their native languages. These talks opened opportunities for the European audience to engage in lively conversations with Taiwanese writers and to experience the acoustic qualities of Taiwanese literature. The invited writers included poets, novelists, and essayists with distinct backgrounds and various writing styles, such as Li Ang (李昂), Chen Xue (陳雪), Liglav Awu (利格拉樂·阿烏), Yang Suang-Zi (楊双子), Lo Chih Cheng (羅智成), and Keven Chen (陳思宏). Their works denote the richness and diversity of Taiwan and Taiwanese literature by tackling issues of gender, LGBTQ+, Indigeneity, race, colonial violence, and social injustices. By artistically and aesthetically articulating the experiences and feelings of the marginalised groups in Taiwan, these writers struck emotional and intellectual chords with their audiences.

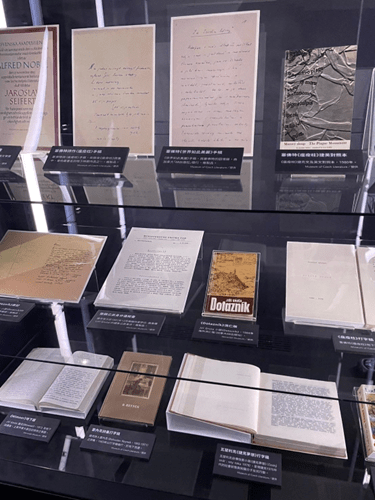

Five months later, the National Museum of Taiwan Literature brought Czech literary history and culture to Taiwan by holding an exhibition, “Typeset Hopes and Dreams: Exhibition on Contemporary Czech Literature” (打字機也會唱歌: 捷克現當代文學展) (December 5, 2024-March 2, 2025). Continuing the momentum from the 2024 ARM that shared Taiwanese literary arts with Central Europeans, this exhibition offers Taiwanese viewers insights into Czech literary and social history in the twentieth century. The exhibition features a variety of archival materials—including manuscripts, images, handwritten letters, and publications—that together construct a historical narrative of the transition from an authoritarian to a democratic regime in Czechia. These archives also embody the unwavering resilience of the Czech people, who constantly negotiated strict censorship and authoritarian power through reading and writing in the twentieth century, showing commonalities with Taiwan’s experiences and struggles around the same time.

“Typeset Hopes and Dreams” narrates twentieth-century Czech literary history chronologically, in alignment with major events that significantly affected the writing and publishing of Czech works. The early twentieth century marked the beginning of modern Czech literature, as more and more writers, such as Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923), began using Czech, the vernacular language commonly spoken in everyday life, in their literary writing. These writers popularised and promoted the vernacular language to carve out their identity as Czechs and preserve Czech culture. Meanwhile, writers like Franz Kafka (1883-1924), one of the most canonical Czech authors and renowned for his novella The Metamorphosis, continued publishing in German (“Typeset Hopes and Dreams” booklet 3). As suggested, the origins of modern Czech literature lie in the search for and solidification of Czech identity while acknowledging the continued significance of the German language in literary development during this period.

Modern and contemporary Czech literary culture manifests an interwoven relationship with political circumstances, changes, and turmoil. The Czech people’s yearning for liberalisation and freedom culminated in the Prague Spring of 1968, a movement advocating for political reforms and democratisation under the Communist dictatorship (1948-1989). However, the Soviet invasion brought the movement to an end that same year. In the aftermath, the government enforced a unified political ideology, suppressed free speech, and imposed stricter censorship on the printing industry, an era known as the normalisation period. “Typeset Hopes and Dreams” presents copies of the secret police’s register book that lists dissidents and “controversial” individuals’ names and information, as well as search warrants, which highlights the government’s gross violations of human rights during this time. Despite political repression and control over publications, the Czech literary culture flourished through the underground press. Writers like Bohumil Hrabal (1914-1997), a prominent twentieth-century Czech author renowned for portraying ordinary people as memorable characters, produced his works using typewriters and distributed them underground after they were banned following the Prague Spring. The exhibition displays the typewriter that Hrabal had used for a long time, which stands as a testament to his tactics to bypass censorship and resist authoritarian control. The thriving underground press and widespread use of typewriters exemplify how Czech writers asserted their subjectivity in defiance of governmental persecution in the 1970s and 1980s, which paralleled the cultural-political climate in Taiwan at a similar time.

Many Czech intellectuals were exiled overseas due to censorship and political oppression in their homeland, yet they played a pivotal role in shaping contemporary Czech literary and cultural traditions. The Canada-based publishing house, Sixty-Eight Publishers, published banned Czech and Slovak literature, thereby serving as a vital platform for amplifying suppressed voices and advancing the Czech literary evolution. For instance, as the exhibition shows, Sixty-Eight Publishers released the manuscript of All the Beauties of the World, a memoir by Jaroslav Seifert (1901-1986), who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1984. Efforts of the exiled writers, together with the Sixty-Eight Publishers, strengthened the people’s resistance to authoritarianism and explicated the transnational nature of Czech literature.

In 1989, two years after the lifting of Martial Law in Taiwan, the Velvet Revolution, a nonviolent political and social movement, finally ended Czech’s one-party Communist regime and fulfilled the people’s long-standing desire for freedom. Its success owed much to the passion and devotion of writers, such as Václav Havel (1936-2011), the first president of the Czech Republic who remarkably contributed to the Prague Spring and Velvet Revolution. Free from censorship, post-Revolution Czech society witnessed the blossoming of the literary scene and a surge in artistic productions characterised by diverse styles and perspectives.

The turbulent path that Czech society and literature traversed found surprising resonance in Taiwanese history and culture during the twentieth century. On a winter afternoon, when my friend and I entered the National Museum of Taiwan Literature, we joked that we had zero knowledge of the Czech language and literature. However, as we examined each archival source and delved into the historical record, we realised that seemingly unrelated Czech and Taiwanese literatures reveal rich opportunities for intellectually engaging dialogue. In the early twentieth century, Czech writers committed themselves to writing in Czech to define their self-identity. Similarly, Taiwanese literature entails a close interrelation with the language used and the process of identity formation. In multilingual and multi-racial societies like Taiwan, Mandarin Chinese never monopolises literary expression; numerous authors incorporate Hokkien, Hakka, Indigenous languages, English, and more into their works. These literary experiments reflect efforts to connect more intimately with the authors’ cultural roots and ethnic backgrounds and further emphasise the diverse nature of Taiwanese literature.

The struggle and resistance of the Czech people in the twentieth century bear similarities to Taiwan’s historical trauma under the authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT) regime from the 1940s to the 1980s. Beginning with the KMT’s declaration of Martial Law in 1949—widely regarded as the starting point of the White Terror period in Taiwan—the government policed and harshly punished political dissidents who opposed the party. The KMT imposed strict censorship and banned publications that suggested anti-party sentiments. Like Czech intellectuals, many Taiwanese people also took pains to critique the regime, expose the cruelty of authoritarian rule, and convey their longing for a free society. The National Human Rights Museum, in collaboration with Spring Hill Publishing, released a four-volume anthology of Taiwanese novels focusing on the White Terror, Let the Past Become This Moment: Selected Works of the White Terror Period in Taiwan (讓過去成為此刻: 臺灣白色恐怖小說選), in 2020. In 2021, an English translation of Taiwanese stories, Transitions in Taiwan: Stories of the White Terror, edited by Ian Rowen, was published. The variety of literary pieces in these collections reminds us of the traumatic experiences Taiwanese people endured over the decades. It also underscores the potential for further in-depth comparative studies of Czech and Taiwanese literatures, particularly in scrutinising how writers exercised agency in confronting authoritarian power through their writing.

The conversation between Czech and Taiwanese literatures has been fostered not only through the 2024 ARM and “Typeset Hopes and Dreams” exhibition but also through a growing number of translations. As the exhibition summarises, the translation of Czech literary works, such as those written by Milan Kundera (1929-2023) and Jaroslav Hašek in Taiwan, has proliferated, especially after the 1980s. Over the last two decades, an increasing number of works penned by Taiwanese authors like Qiu Miaojin (邱妙津) (1969-1995) and Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) have been translated into Czech. This expanding body of translations in both countries broadens the readership of Taiwanese and Czech literary works, as well as their marginalised experiences. Moreover, it lays the foundation for deeper and more fruitful dialogue, with further exchanges and collaborations yet to bloom.

Li-Ting Chang is a Ph.D. candidate in East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research interests include Chinese literature, print media, affect theories, gender studies, Taiwan studies, Sinophone studies, and popular culture. Her dissertation project, “Dear Darling: Love Letters as a New Cultural Sensation in Early 20th Century China,” explores the interplay between romantic sentiments and the love letter as both a literary genre and an everyday practice. She is also an advisory member of the UCSB Center for Taiwan Studies (CTS) and one of the organisers of the Taiwan Studies Workshop (TSW). From 2023 to 2024, she served as a program commissioner for the North American Taiwan Studies Association (NATSA).

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Farewell 2024, Fresh start 2025?’.