Written by Mu-Hsi Kao Lee.

Translated by Chee-Hann Wu.

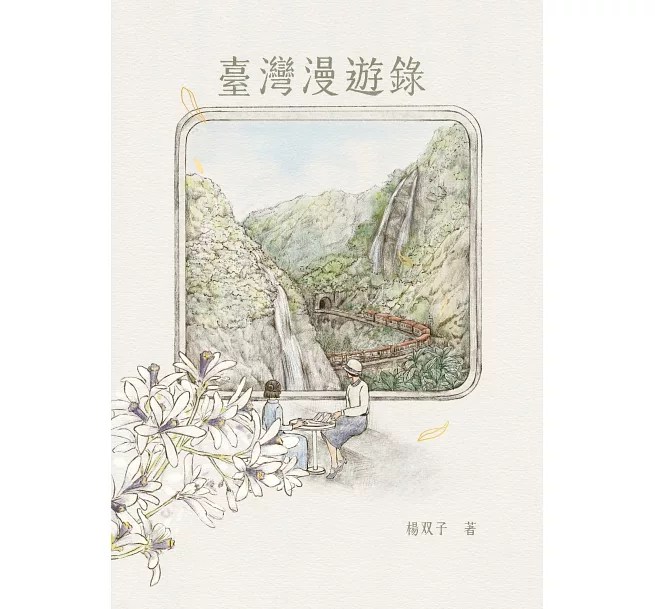

Image credit: Taiwan Travelogue cover, Spring Hill Publishing.

“Why does this book feel kind of like a light novel or a romance novel?” my partner asked while peeking over my shoulder. I had just started reading the first chapter of Taiwan Travelogue on our shared e-reader, and they leaned in to silently read a few pages alongside me before making that comment. I chuckled quietly—not just that, I thought, it’s a yuri (lily; girls’ love) novel! Even though the genre label “historical yuri novel” is clearly stated in the translator’s preface within the first few pages, and the author has brought it up multiple times in interviews, what most immediately and unmistakably conveys that intention is the narrative itself—its light and lively tone, and the vivid, sharply drawn character portrayals and their interactions.

Is this going to be a story about a woman writer from the Japanese Empire—someone who holds the power of narrative—arriving in colonial Taiwan and stumbling into curious sights and unforgettable encounters with “mysterious and wondrous” characters? Of course, it is! Holding onto thoughts like “I knew it!” and “But what’s going to happen next?” along with “These dishes and foods are making me so hungry,” I read from overseas—not in Japan, not in Taiwan. As I read, I came to understand detailed, unfamiliar slices of cultural life during the Japanese colonial period.

At the same time, the words pulled me into a renewed imagining and longing for home. From the perspective of the protagonist, Aoyama Chizuko, I felt my own emotions and gaze rise and fall with her—her moments of heart-fluttering excitement, occasional boredom, spontaneous wonder, and fascination with what’s in front of her, and her fierce attachment to her translator O Chizuru. It all stirred me in ways that brought me back to a younger version of myself, devouring vast amounts of BL (boys’ love) and yuri novels, light novels and fanworks/dojinshi of all kinds during my teenage years.

I knew exactly what I was reading, and I had a sense of where the plot might go—and yet, I still felt adrift, suspended between satisfaction and endless craving. I kept thinking, maybe I’ve had a bit too much, but what’s the point in trying to restrain this appetite, this obsession, this giddy excitement, when it doesn’t hurt anyone (well, maybe just myself)? Even I couldn’t pin down exactly how I felt. Was this some form of love or obsession? A return to the warmth of all-girls’ school days and intimate female friendships? Or maybe it was the thrill and trembling caused by the pull between people, the taboos shaped by time and place, the subtle, unspeakable tensions of desire and difference, all from those formidably appetising tidbits of food, desires, and affections.

And then there was a kind of excitement—a yearning for a new perspective in fiction, one born from the interweaving of historical evidence and literary narrative, women’s writing and emotional entanglement, the many-layered unique elements of the land of Taiwan. All of it tangled together, simmered and absorbed through the act of reading—like that bowl of dau-mi, potato noodle stew O Chizuru never managed to cook for Aoyama Chizuko, ending up, somehow, in my own stomach instead.

From the eyes of this enraptured reader, I wonder: is this story a confession etched by Aoyama Chihuruko herself, seen through her gaze, carved out by her own hands? Or is it a portrait of O Chizuru, a modern woman of the colony—being written, watched, and desired—yet ultimately revealed in the author’s memory as someone who claims her agency, who leads and shapes the relationship on her own terms?

The structure of the fictional author and translator of Taiwan Travelogue is cleverly designed—it carves out space for historical and cultural annotations, allowing various editions and translations across different eras to reflect the trajectories and lived experiences of Taiwan and some of its people. This structure also deepens the temporal and cognitive gaps that shape the interactions and bonds between the two protagonists. To me, Yang Shuangzi’s narrative is very clear, leaving little “room for interpretation” in its meta-framework. The story’s plot is straightforward to follow, yet when paired with authentic historical and cultural references, this clarity ironically forms a distinct frame that invites readers to momentarily step outside the narrative—to pause and reflect on the views or scenes enclosed within.

Do the two protagonists “end up together”? Do they “reconcile”? What becomes of them later? The book doesn’t spell it out as ambiguously as the feelings between Chizuko and Chizuru—it turns the tangled, swirling emotions I had while reading into a long, drawn-out resonance, fine and lingering. It also gently nudges the reader’s gaze elsewhere: Aoyama Chizuko, an imperial visitor, driven by her sense of “upright justice” and personal affection, defends O Chizuru and even speaks up for colonial Taiwan—this chivalrous behaviour is reminiscent of the cool, bold seniors from our school days, or the bright and free-spirited male lead in a shojo manga.

When these familiar character tropes and narratives intertwine with the complex identities of coloniser/colonised and the unreliable first-person perspective of Aoyama Chizuko, what emerges is a portrait of raw, earnest emotion—an intense desire for companionship, an innocent yet consuming hunger to be near and to understand the one who matters. Whether interpreted as a metaphor for colonial conquest and power or as an individual’s thirst for knowledge and irresistible emotional connection, this “beast of desire” devours the moment with full appetite, seeking warmth out of its “naïveté.”

Even though the story of an imperial writer visiting Austronesian Taiwan—with two women from opposing standpoints but shared emotional and intellectual sensibilities—frames the tale as a dual-layered journey (personal and material), it does not rely on the perilous dramas of romance novels—no life-threatening disasters, no conspiracies, or cruel tests. Grounded in the historical realities surrounding them, the protagonists’ sharp, resilient personalities and expressive emotions need no embellishment or fantasy: these are already vast divides. And it is precisely within the ordinariness of an extraordinary time—through shared meals, language, verbal sparring, and the intimacy of gestures—that their delicate, beautiful connection glimmers, always teetering between closeness and distance, like a once-in-a-lifetime encounter.

I sincerely hope that Taiwan Travelogue will travel farther and wider through translation and word-of-mouth, inspiring more people to recall and reflect on the complex and beautiful friendships they’ve experienced and the struggles and contradictions within their own identities—reading with their own eyes, savouring it carefully, chewing it over, and holding it in their hearts.

Mu-Hsi is a theatre producer and educator, community organiser, and art administrator dedicated to public engagement. Working on her MA degree in Theatre at CUNY Hunter College, she is also a baseball fan, an ACG and fandom lover, and a public library worker.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Mapping Taiwan: Literary Paths and Real Journeys‘.