Mark Gerard Murphy

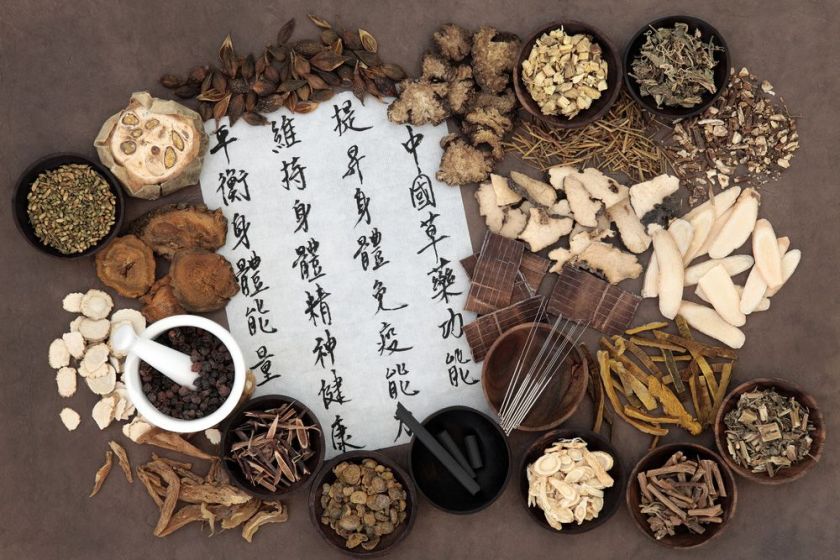

Image: Dr. Bret Mosher, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Summary: Traditional Chinese Medicine has developed along two divergent paths since 1949: mainland China created a standardized, state-controlled system that serves nationalist goals, while Taiwan’s TCM evolved more organically into a diverse, pluralistic tradition that preserves multiple interpretive approaches. Both claim authentic Chinese heritage, but their different political contexts produced fundamentally different relationships between tradition and modernity, raising questions about cultural authority and who gets to define “authentic” Chinese medicine.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) functions as far more than a therapeutic system—it serves as a living repository of cultural memory, a vessel for collective identity, and a tool of political articulation. Its practices, theories, and institutions traverse the complex terrain of language barriers, geographical boundaries, and the deep fissures left by historical trauma. In the fraught relationship between Taiwan and mainland China, TCM emerges as a particularly contested domain of cultural authority. Both societies lay claim to their authentic inheritance. Yet, each has moulded it according to distinctly different imperatives, pressing ancient healing wisdom into service for competing visions of what cultural identity means in the modern world.

This divergence runs deeper than mere policy differences. While both Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China invoke TCM as evidence of unbroken medical continuity stretching back through millennia, their approaches to preservation, modernisation, and global projection reveal fundamental tensions about tradition’s role in contemporary society. The mainland’s systematic integration of TCM into state-sponsored healthcare reflects socialist ideologies of scientific modernisation and cultural nationalism, while Taiwan’s development of TCM has been shaped by democratic pluralism, market forces, and the particular pressures of maintaining cultural distinctiveness amid geopolitical isolation. These contrasting institutional logics have produced not merely different healthcare systems but competing epistemologies of healing, each claiming authentic Chinese heritage while embodying radically different relationships between tradition and modernity, state and society, local practice and global aspiration.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has invested heavily in the construction of a unified national medicine. After 1949, the Communist Party did not dismantle TCM; instead, it restructured it. In the early years, this took the form of institutional integration: Chinese medicine hospitals were created, university departments built, and a formal curriculum devised. Diagnosis and treatment had to align with state-defined categories—standardised point locations, syndromes, and formulae. The aim was clear: to forge a modern, scientific image of Chinese medicine that would stand beside biomedicine, recognisable to international observers yet rooted in national heritage.

Mao Zedong’s role was paradoxical. Privately dismissive of TCM, he nonetheless championed its public promotion. In practice, this meant shaping it into a structured system, simplifying textual interpretation, marginalising regional lineages, and erasing much of its cosmological and esoteric content. The result was a narrowed version of Chinese medicine—technically legible, institutionally functional, but no longer reflective of its full historical range.

Across the Taiwan Strait, a markedly different trajectory emerged under fundamentally altered political and social conditions. When the Kuomintang (KMT) retreated to Taiwan in 1949, they carried with them not only the apparatus of the Republic of China but also represented a continuation of Chinese civilisation itself. This cultural mandate theoretically encompassed Chinese medicine as part of the broader civilisational inheritance, yet the exigencies of survival and modernisation on the island dictated other priorities. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as the KMT government focused on economic development, military preparedness, and Western-oriented modernisation, TCM received minimal formal state support. Instead, it persisted through more informal channels—sustained by private practitioners, transmitted through family lineages, and maintained by persistent patient demand that refused to be extinguished despite official neglect.

This marginal existence proved paradoxically generative. It was not until the democratic opening of the 1980s, when civil society began asserting its voice against authoritarian rule, and the comprehensive health insurance reforms of the 1990s, that Chinese medicine finally achieved full professional recognition within Taiwan’s evolving healthcare system. By then, however, decades of relative autonomy had allowed a distinctly different medical culture to crystallise—one characterised by remarkable diversity of method, interpretation, and practice. As Mario Buonomo states ‘Although this push toward modernising TCM based on a scientific paradigm continues up to our age, in Taiwan – and everywhere globally – the tradition has not disappeared. The dynamics between tradition and modernity have hybridised.’

Contemporary Taiwan’s TCM landscape remains marked by this pluralistic heritage. While formal licensing requirements and academic training programs now exist, the system preserves considerably more space for individual schools of thought, master-apprentice lineages, and unorthodox clinical approaches than its mainland counterpart. Some practitioners draw heavily on Daoist internal cultivation practices, integrating meditation and qigong into their therapeutic repertoire. Others have revived classical dynasty-era interpretations of pulse diagnosis or incorporated Japanese Kampo modifications developed during the colonial period. Still others experiment with hybrid approaches that blend traditional diagnostics with modern nutritional science or psychological counselling. Taiwan has thus evolved into something of a sanctuary for interpretive traditions and experimental practices that struggle to survive under the People’s Republic’s more rigid institutional discipline and standardisation imperatives. This diversity reflects not merely tolerance but a fundamental philosophical commitment to preserving the multifaceted nature of Chinese medical knowledge. In this living laboratory, ancient wisdom continues to adapt and evolve in response to contemporary needs.

That said, the temptation to romanticise Taiwan as a haven of medical freedom deserves critique. Taiwan’s own institutions apply forms of standardisation. Licensing exams, textbook production, and regulatory oversight produce their own kinds of uniformity. Its TCM education has increasingly incorporated biomedical training, and public clinics face similar pressures toward cost-efficiency and standardisation as those in the PRC. Moreover, the legacy of Japanese colonialism (1895–1945) shaped Taiwan’s medical infrastructure, subtly influencing herbology, diagnosis, and clinical methodology. TCM in Taiwan, therefore, bears the marks of multiple modernities—Republican Chinese, colonial Japanese, and post-war American—all layered over a foundation of pre-modern Chinese practice.

Still, Taiwan has retained more space for interpretive and textual heterogeneity. In the PRC, the medical classics have been politically curated. Certain texts are elevated, others sidelined. Commentary must remain within the bounds of Marxist materialism, and the metaphysical language that once permeated Chinese medicine—the relations between qi, shen, and cosmology—is often reduced to biochemical metaphor. In Taiwan, by contrast, medical scholars explore Daoist texts, minority traditions, and even foreign interpretations with relative freedom. The result is a more polyphonic discourse.

Internationally, these differences surface through visibility and silence. The PRC’s efforts to globalise TCM are extensive: through Confucius Institutes, state-sponsored hospitals abroad, and integration into the WHO’s diagnostic manuals. TCM is framed as an export commodity, a tool of soft power, and a proof of Chinese civilisational depth. Taiwan, excluded from most international bodies, must operate through informal channels. Yet it does so with surprising reach: Taiwanese-authored texts circulate among diaspora practitioners, and its schools train students from across Southeast Asia and beyond. Practitioners in North America and Europe often find themselves navigating between two knowledge systems—one shaped by the PRC’s institutional coherence, the other by Taiwan’s scholarly pluralism.

Political tension manifests in how each side frames medical legitimacy. Beijing insists on a singular Chinese culture, of which it alone is custodian. In this view, Chinese medicine is inseparable from the Chinese state. Taiwan, especially in recent years, has sought to foreground its distinctiveness—not by denying its Chinese roots, but by emphasising hybridity. Some scholars in Taiwan refer to their system as “Taiwanese Chinese Medicine,” acknowledging both inheritance and divergence. They incorporate indigenous knowledge systems, Japanese colonial archives, and contemporary research into one evolving medical discourse. This hybridity is strategic as much as historical. Faced with diplomatic isolation, Taiwan has sought to internationalise its medicine through openness rather than exclusivity. Where the PRC offers a standardised curriculum, Taiwan offers a more varied research ecology. Where the PRC focuses on global market penetration, Taiwan focuses on scholarly depth and regional adaptation. These are, of course, broad tendencies, but they point to real differences in orientation.

Still, the distinction between the two systems should not be overstated. Taiwanese medical colleges have adopted many of the same textbooks as mainland institutions. The language of “syndrome differentiation” (bianzheng lunzhi) remains dominant in both contexts. Clinical methods overlap. Many Taiwanese doctors receive their pharmacological materials from mainland sources, and many mainland doctors study texts published in Taipei. The traffic is two-way, though uneven.

Where the divergence becomes politically acute is in claims of heritage and representation. When the WHO included TCM in ICD-11, it did so based on classifications shaped by PRC medical authorities. Taiwan’s contributions to this global move went unrecognised. At stake was not just institutional visibility, but cultural authorship: who speaks for Chinese medicine? Who defines it? Who carries it forward? Such questions draw attention to the wider stakes of tradition as such. Chinese medicine has always evolved—through empire, migration, war, and reform. Its boundaries have shifted across time. What counts as “authentic” has always been under negotiation. The PRC asserts one answer: tradition must be legible to the state, harmonised with science, and projected outward as a unified narrative. Taiwan proposes another: tradition can coexist with disagreement, adaptation, and multiplicity.

Neither model escapes the pressures of modernity. Both systems regulate, institutionalise, and reshape the past in light of present needs. Yet the question remains whether cultural continuity requires singularity. Taiwan’s experience suggests that it does not. Through the absence of central control over classical interpretation, Taiwan has preserved forms of medical reasoning that offer alternatives to the homogenised global discourse of health.

The politics of TCM, then, cannot be reduced to soft power or cultural pride. It involves institutional epistemology—how knowledge is shaped, preserved, and taught. It involves access to international forums. It involves pharmaceutical regulation, patient expectations, and clinical infrastructure. But it also involves deeper philosophical questions: What is the role of the classic in a modern medical system? Can a tradition be both coherent and diverse? Must the borders of a nation-state enclose it?