Written by Bryn Thomas.

The way societies remember war is never neutral. Memorials, monuments and lists of dead shape not just history, but what a society chooses to remember.

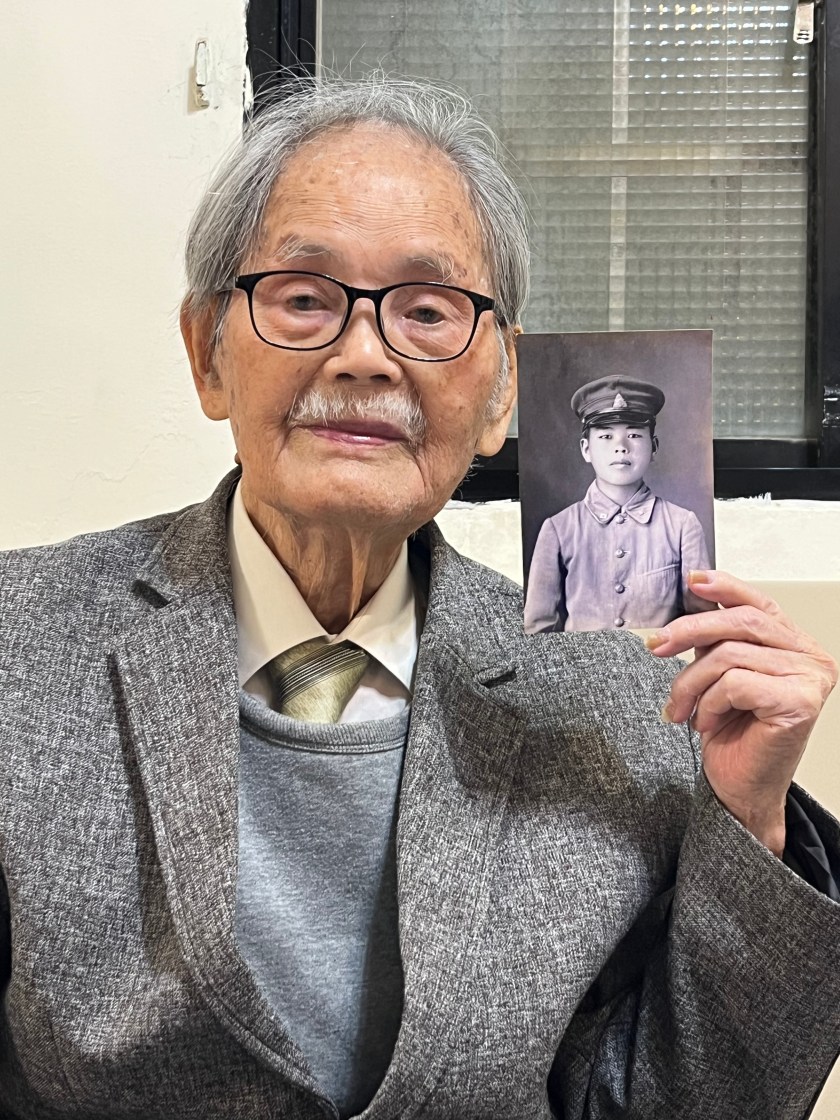

Yang Fu-cheng has worked to have his countrymen memorialised for years. He’s a former Japanese auxiliary and a known advocate for Taiwan’s Imperial Japanese veterans. When my team interviewed him at his home in Keelung, Taiwan, in February 2025, he told my team:

“History is written by the winners, that’s how war works.”

On June 23, 2025, Yang — still able to travel at 103 — joined an unofficial delegation from Taiwan bound for Okinawa. There, they marked 80 years since the end of the battle for which the Japanese island is best known. The group, partly organised by a Kaohsiung-based veterans’ organisation, was there both to commemorate those who died in 1945 and to shed light on a lingering World War II mystery: the question of Taiwan’s missing war dead. Like Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where Japan honours its war dead but enshrines war criminals, the Okinawa Peace Memorial reflects realities about who is remembered — and who is not.

The memorial is home to a monument listing Taiwan’s war dead with just 34 names. It’s a number many people, including Chu Chia-huang from the Taiwanese Veterans Organisation, think is far too small:

“So, adding everything up, Matayoshi Morikiyo, a professor from Okinawa University, believes that the number of Taiwanese who died on Okinawa should be well over 1,000.”

Based on this and considering that Japanese forces suffered a casualty rate of over 90% during the battle, it’s reasonable to assume that at least 1,000 Taiwanese troops took part. In truth, this remains an estimate. There are no clear records showing how many Taiwanese served, in what capacities, or how many died.

Now consider what a Taiwanese person today must do if they want to have a family member’s name added to the Okinawa Peace Memorial. First, they must provide proof that the individual died during the battle, such as military records or other official documents. Once submitted to the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, the information is reviewed by historians if needed. If approved, the name is inscribed. And all this with limited support from the Taiwanese government.

But in reality, when it comes to the battles fought in the Pacific Theatre at the end of World War II — Okinawa, the Philippines, and Iwo Jima — studying Taiwan’s role is often more an exercise in understanding what we don’t know, and more importantly, why we don’t know it.

To make sense of it, we can start with what we do know: Taiwan’s role in the Japanese Empire and the state of affairs in 1945; the scale and nature of the battle; the limitations of relying on records from the time; the ongoing discovery of remains in Okinawa today; and the political realities and expediencies faced by the ROC, the U.S., and Japan in the immediate postwar period.

We know that approximately 200,000 Taiwanese served the Japanese Empire during the war with the United States and its Allies, and estimates suggest that around 30,000 died in service. Some, like Yang Fu-cheng, volunteered enthusiastically; others were conscripted or forced into service. Most served in support roles, such as translators and logistics personnel. A few, particularly from Indigenous communities, were pushed into combat roles as early as 1942.

In truth, Japan’s military was initially reluctant to put colonial subjects into combat roles. While the Special Volunteer System of 1942 and the Imperial Navy Special Volunteer System of 1943 provided avenues for enlistment, large-scale recruitment of Taiwanese troops did not start until 1945. However, some Taiwanese units were formed in 1944. Taiwanese soldiers recruited in this time frame faced just four possible major campaigns in which to die: those in the Philippines, in Burma, on Iwo Jima and on Okinawa – and that’s if their ship was not sunk on the way.

Yang Fu-cheng told us this about being deployed to Singapore in 1944:

“We heard when we arrived [in Singapore] that the troop carrier that left before us and the carrier that left after us had been sunk. We got very lucky.”

Things were much worse by early 1945, a time when the Japanese Empire was being rolled up by the Allies and growing desperate. In our interview with historian Professor Mike Lan from National Chengchi University, he pointed out that the record-keeping of enlisted men was spotty.

The names of Taiwanese conscripts—some of whom were illiterate— were fudged, written in Japanese, misspelt, or recorded alongside the names of ethnic Japanese soldiers. Taiwanese – including former President Lee Teng-hui – were frequently assigned to units alongside Japanese troops. When they died, their names were often recorded as Japanese soldiers if they were recorded at all.

Information and news about the course of the war were strictly controlled in Taiwan, and letters written home were censored. Families of Taiwanese soldiers who died serving in the Japanese military during World War II sometimes received official death notifications, but they were often vague. Chu Chia-huang from the Taiwanese Veterans Organisation told us that they often used nondescript terms, such as Nan’yō (南洋), to indicate the broader region of death — the Japanese designation for their South Seas Mandate territories and other parts of Southeast Asia.

Making matters worse is that many records did not survive the conflict. In the late-war period, the U.S. torpedoed Japanese ships indiscriminately, firebombed Japanese cities, and made little distinction between enemy combatants and colonial subjects. In our April interview, Cambridge University Professor Barak Kushner told us the Japanese themselves intentionally destroyed certain records. While Chu told us the nearly total casualty rate meant few were left over to share oral histories as well.

During the Battle of Okinawa in the spring and summer of 1945, many Japanese soldiers were forced to fight to the death or commit suicide in violent attritional battles from the Islands’ many caves. To quote our June interview with military historian John C McManus.

“In the late war period, the US is starting to rely more and more on one of humanity’s oldest weapons: fire.”

Flamethrowers and satchel charges were used to burn or suffocate Japanese infantry and civilians hiding in caves alike. Cave entrances were often sealed with explosives. Records show that Sherman ‘Zippo’ flamethrowers were in constant demand during the campaign.

The brutal fighting led to dehumanisation on both sides, and little respect was paid to Japanese war dead during and immediately after the battle. Although the U.S. military gave some soldiers formal burials, others were left sealed in caves or dumped into the ocean as airfields were cleared on Okinawa. A recent AFP report on local bone collectors noted that remains continue to be found, and that around 1,400 people on the island are still awaiting identification. Another article highlighted the fact that around 1.2 million of Japan’s war dead, across Asia, remain unaccounted for – what percentage of that number is Taiwanese is uncertain.

“At the end of the war, I don’t think anyone was focused on memorialisation.” John C. McManus told us, adding:

“Nobody’s big concern, in the immediate aftermath, was commemoration, or figuring out remains; everyone’s idea was “let’s move on,” and if you’re Okinawan, your idea was “I’m happy I survived.”

Some 100,000 Okinawan civilians died in the battle – about a third of the island’s wartime population. Their remains are often mixed with those of Japanese soldiers, upwards of 115,000 soldiers, further confusing identification.

The postwar political situation in Taiwan was even more complex. On October 25, 1945, Japan formally handed Taiwan over to the Republic of China (ROC), and its people went from being subjects of a defeated empire to citizens of one of the victors. The role of Taiwanese soldiers who had fought for Japan quickly became politically inconvenient in the emerging Cold War order. In recording the war’s history, the ROC emphasised its own veterans. It built memorials such as the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine in Taipei, constructed on the site of a former Shinto shrine. To this day, no official memorial in Taiwan honours or names the island’s soldiers who served in the Japanese Imperial forces.

And really, one would have to ask if having one is appropriate. Between 10 and 17 million Chinese civilians died from famine, massacres, disease, and starvation brought on by the war between 1937 and 1945. After the Chinese Civil War, up to 1.2 million mainland Chinese fled to Taiwan, and few of them had much affection for the Japanese Empire — or for those who had served it. The use of soldiers from Taiwan as translators in China or in Chinese-speaking communities in Southeast Asia is well documented, even if their exact numbers are not.

The same veteran we interviewed, Yang Fu-cheng, although mainly involved in logistics, was linked to massacres involving Hokkien-speaking translators in the film From Island to Island. We like, like the film’s director, pressed him on Japan’s excesses.

“The war was necessary to free Asia from European colonialism,” he told us. “And in war, bad things happen.”

His words echo the propaganda of Japan’s wartime “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” — the Empire’s justification for conquest under the banner of Asian liberation.

But Japan never lived up to its own marketing. Taiwanese were always treated as second-class citizens in Japan’s racial hierarchy – and while many were stuck in difficult situations during the war, any true research into the nitty-gritty of Taiwan’s wartime role, who fought and who died where, will dig up some truths that people here may not want to face.

And so, remembering Taiwan’s war dead isn’t just about filling in historical blanks—it’s also about deciding what kind of history Taiwan wants to claim. Eighty years have passed, and the last living witnesses from that era are fading. Without concerted government effort, it is unlikely we will ever achieve a full assessment of the role Taiwan’s troops played in the Battle of Okinawa—or the war itself. More likely, only the 34 Taiwanese names currently inscribed on the island’s monument will ever be remembered.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Between Empires and Allies: Documenting Taiwan’s WWII Experience‘. All articles of the special issue are written independently of TaiwanPlus News.