Written by I-Yun Lee.

Translated by Chee-Hann Wu.

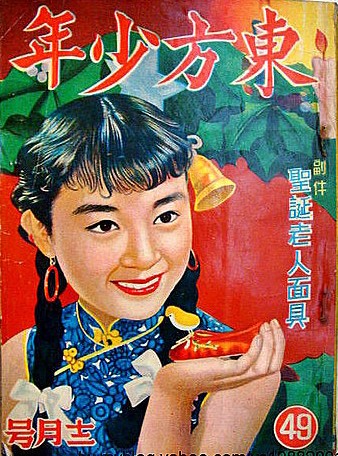

Image credit: Oriental Youth cover.

The visual grammar of modern comics was introduced to Taiwan by Japan during the Japanese colonial period (1895-1945). “Modern comic grammar” refers to drawing in panel divisions on a page, with each panel functioning like a stage viewed front-on by the reader—no high or low camera angles, no shifts in focal length, characters shown in full-body shots, almost no changes in facial expression, and with an action in each panel, 99% of which is simply speaking. The panels were generally evenly divided. This style persisted until 1947, when Osamu Tezuka’s New Treasure Island introduced extensive cinematic techniques, opening the door to a postwar comic grammar that featured changes in angle and focus and used images alone without text or dialogue to advance the story. More importantly, they employed close-up shots that created a more intimate relationship between character and reader. Tezuka also developed a system of expressive symbols that made characters’ expressions much richer.

This new postwar Japanese comic grammar circulated into Taiwan through children’s general-interest magazines such as Schoolmate (Xueyou) and Oriental Youth (Dongfang Shaonian), which began publishing translated Japanese comics after 1953. Due to sensitivities within the Republic of China government stemming from the Sino-Japanese War, these translations removed any trace of Japaneseness; for instance, author names and character names were changed to alternatives such as “Bai Xue,” “Heibai,” and “Quan Ji.”

The 1960s marked the golden age of rental comics in Taiwan. As early as the 1940s, rental comics had circulated, primarily Shanghai-style lianhuanhua, literally translated as linked-picture books, which appeared in horizontally shaped, palm-sized booklets with usually only one framed image per page and captions placed outside of the frame. In the 1950s, translated Japanese comics joined the market. By 1960, children’s general-interest magazines had been overtaken by pure comic magazines such as Comics King (Manhua Dawang) and later Taiwan Comics Weekly (Taiwan Manhua Zhoukan). At that time, editors Liao Wen-mu and Tsai Kun-lin of Oriental Youth decided to leave the publisher and establish Wenchang, a rental comic press. Using the strategy of publishing one comic book per day, they opened up the rental comic market. Soon, rental comic publishers sprang up across Taiwan, and the rapid and mass publication of comic volumes had gradually overtaken the market share of weekly comic magazines. Meanwhile, this coincided with the booming popularity of martial arts films and novels, making martial arts comics the most sought-after genre and propelling artists like Yeh Hung-chia, Lei-chiu, Fan Yi-nan, and Chen Hai-hong to prominence.

Just as rental comics were taking off, in 1962, the ruling Kuomintang government promulgated the “Directives for Publishing Comics.” This caused widespread panic among rental bookstores and publishers, who petitioned the government, noting that their readership consisted not of children but of working-class adults. Nonetheless, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Education announced that starting September 1, 1965, all comics had to be submitted for prior review. Without review approval and a publication permit, publication was prohibited. This requirement applied not only to new comics but to all previously published works as well. Despite these regulations, it was not until March 1966 that the Ministry of Education began accepting submissions for review. Moreover, comic review fees were pegged to textbook review fees, which were forty times the price of a comic (3 NT dollars). In 1966, this amounted to 140 NT dollars per book, placing a heavy financial burden on local artists. The restrictive review standards severely curtailed freedom of expression and imagination, forcing many artists to cease drawing or change careers entirely, resulting in a generational gap among Taiwanese cartoonists.

Under these conditions, many publishers began hiring apprentices to trace Japanese comics and adapt them into the familiar Taiwanese rental-comic format of three equal panels per page instead. In other words, although Taiwan had encountered Tezuka’s postwar comic grammar in the 1950s, by the 1960s, only small amounts of it were actually absorbed. The widespread adoption did not occur until photocopiers became common in 1975. After 1977, numerous publishers specialising in reprinted Japanese comics were established. Instead of relying on apprentices to hand-trace and print comics, they began using photocopiers to reproduce Japanese works in bulk to reduce production costs and submit them for review. Despite the ongoing infringement of local artists’ work due to censorship, between 1977 and the beginning of the “Comics Cleansing Movement” in 1982, the market enjoyed a period of rapid growth for the mass production of pirated Japanese comics.

In 1982, the mainlander (waishengren) Taiwanese cartoonist Niu Ge led a campaign accusing the National Institute for Compilation and Translation, the agency responsible for reviews, of approving Japanese comics that corrupted morals and unfair review standards for Japanese and Taiwanese comics. Leveraging connections among Niu Ge, the military, the arts and culture sector, and senior government officials, this “Comics Cleansing Movement” gained traction. The Government Information Office subsequently passed the “Guidelines for Rewarding the Crackdown on Illegal Comic Publications.” From July to December 1985 alone, local information bureaus confiscated one million comic books. Eventually, the Taiwanese comic market experienced more than a year during which Japanese comics virtually disappeared from shelves between 1986 and 1987, when martial law was lifted, and the comics censorship system was abolished.

The history of comics in Taiwan, particularly from the 1940s to the 80s, reveals a medium with multifaceted appearances, continually shaped by colonial influence, state regulation, and the shifting desires of its readers. From the importation of modern visual grammar from Japan to the rise and suppression of rental comics, the trajectory of Taiwanese comics has never been a straightforward story of artistic development, but rather one of negotiation—between foreign models and local practices, between market forces and governmental control. Furthermore, the comic review system led to a nearly 20-year gap in Taiwan’s comic creation. These tensions not only determined what could be drawn or distributed but also forged the distinctive conditions under which later generations of Taiwanese comic artists would emerge, inherit, and transform the form.

More references can be found in the author’s monograph, Taiwan Comics: History, Status and Manga Influx 1930s–1990s, translated by Timeea Cosobea.

I-Yun Lee is a professor of Taiwan’s cultural history at National Chengchi University. She holds a PhD in Humanities and Sociology from the University of Tokyo (2007) and has published widely in Chinese and Japanese, in particular, on comics in Taiwan and Japan.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Taiwan Drawn: Comics and Graphic Novels.’