Written by Leona Chen.

Image credit: author.

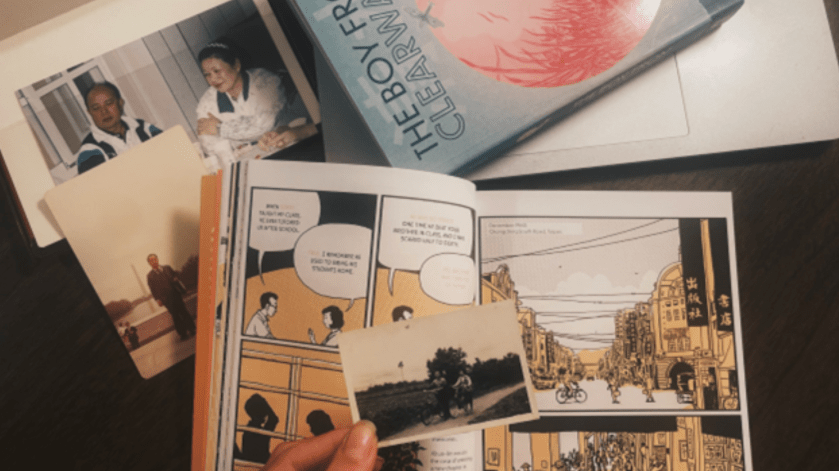

The Boy from Clearwater (來自清水的孩子) speaks to me in my grandfather’s voice.

The award-winning, two-part graphic memoir, written by Yu Pei-Yun, illustrated by Zhou Jian-Xin, and translated by Lin King, knits together two subjects: 蔡焜霖 Tsai Kun-lin’s life story, and Yu’s own transformational experience interviewing him. This blended format of a co-created, intergenerational memory was the first of many parallels in The Boy from Clearwater that resonated with me. Tsai’s courage in sharing honestly and Yu’s humility in listening compassionately mirror the rich gifts I’ve received in my own life from the storytelling of Taiwanese American elders who, like Tsai for Yu, became my chosen ancestors.

The second parallel is more literal: my late grandfather’s name, 江清水, echoes exactly the hometown of the protagonist —modern-day 清水區—from which the memoir takes its title.

My Agong was born in 1934, just four years after Tsai Kun-lin, and just one year before the destructive Hsinchu–Taichung earthquake depicted in the opening scene of Part 1. Tsai and Agong were men of the same generation, shaped by the same turbulence of serial colonisation and dispossession. Which means that before my grandfather became the serious, scholarly man I remember, he too was once a boy, ruddy-faced and inquisitive, finding his footing among his siblings and schoolmates, through regime and curriculum changes; balancing the shifting boundaries of a world recalibrated by empire.

I look for Agong’s likeness among Zhou Jian-Xin’s exquisite illustrations: the knobby knees of adolescence, the prim posture of schoolchildren, the sweet little hat Kun-lin wears to shade him from the sun. Their gestures and textures bring to life a childhood and world I know so little of, but in examining them, I remember that because Tsai and my Agong share a history, through one, I can draw closer to the other. Like Yu, I can choose to be moved by anyone to whom I give my care and attention.

It is a classically diasporic impulse to refract Taiwan’s history through our grandparents, who are our long-suffering geographic anchors but also proxies of everything we long to understand about our past and heritage.

We Taiwanese Americans are especially needy and necessary readers of translated Taiwanese literature, with our voracious appetite to be told who we are and what it all means. And, regretfully, we must be spoon-fed such narratives through the coordinated labours of translators, editors, and publishers because we sit inconveniently at a double remove: geographically estranged and linguistically illiterate, but culturally adjacent enough to know that this is what we crave.

In this context, The Boy from Clearwater offers a particular kind of satiety. Although the memoir’s explicit aim is to document Tsai’s life and legacy, the work also performs the vital task of reconstructing the social world through which an entire generation of Taiwanese youth came of age and into political consciousness. In its sparse dialogue, exposition, and expressive panels, the book becomes a useful medium for diasporic projection and reflection.

Of the gingham qipao Tsai’s mother, Lua Uat-kiao, wears: is this what my great-grandmother wore, too?

Of the wartime prospectus that suspended education beyond elementary school: what would Agong have to say about this?

Its format, unlike other more verbose or self-conscious genres, also distills this history from its own compulsion to over-explain. In these illustrations, things just are — and it is the reader’s pleasure and privilege to study them closely, and decide for ourselves what is central to the story we are extracting.

To witness Tsai Kun-lin grow up under these circumstances — Japanisation and Sinicisation, unjust incarceration, political persecution even after release — is to apprehend our grandparents in a startling new way, but also to recognize a parallel possibility for ourselves. The story reveals, with a rare frankness, Tsai’s private humiliations and miscalculations, but also how profoundly coercive and restrictive his conditions were on his choices and the people implicated in them.

I was particularly drawn to Zhou’s illustrations of Kimiko (Tsai’s wife) in Book 2: her pursed lips when Tsai’s back is turned; the worried curve of her eyebrows as she assures a colleague, despite the improbability, that the debts they owe will be repaid. The children of activists may also find another panel familiar: Tsai’s distant look while his young son gestures for his attention. Without judgment and with great tenderness, Zhou captures how ideological commitments sometimes have a gravitational force superseding the mundane duties of parenthood. There is no escalated, dramatic confrontation between husband and wife or father and child depicted; only the small, repeated disappointments and doubts one might interpret from their expressive faces.

In many of the self-aggrandizing memoirs of political figures, such familial sacrifices are often portrayed as inevitable collateral, tidily accounted for in mercenary rather than moral terms. But in The Boy from Clearwater, the creators deliberately restore Kimiko, their children, and their friends and family to the frame, allowing the readers to see the strain, the steadfastness, and the emotional infrastructure that undergird Tsai’s public achievements. Most importantly, they leave it to us as readers to decide whether to treat those family members as peripheral and marginal, especially in the scarcity of dialogue, or as central agents whose suffering and decisions are equally important to the story.

Though Tsai and his peers are exceptional figures in Taiwanese history, it is these everyday vignettes that are most striking, reminding us that anyone, from anywhere, can be moved towards goodness in the face of injustice; and that anyone, from anywhere, can deserve grace when they falter. These moments destabilize our instinct to cast history as a linear epic of legends, heroes, and villains. Instead, The Boy from Clearwater reframes all political pasts and possibilities as a composite of ordinary emotions and conflicts — hunger, loyalty, debt, friendship, trust — through which a moral and political life is charted and given salience.

It is worth noting that The Boy from Clearwater is exceptionally precious because it is one of few translated works that have achieved publication in the United States (to my knowledge, it is the only translated graphic novel on Taiwanese history to be published here at all). Its existence stands for the series of extraordinary obstacles it has had to survive: securing local legitimacy in Taiwan, then international endorsement, and finally swimming upstream against the tide of every other story that demands our attention. Translation across international markets is never just an act of language (though polyglot translator Lin King does this with astounding deftness), but a life-changing triumph of legibility, rendering a political history and collective memory accessible.

I would have liked to read this book with my grandfather — me enjoying this English translation; him wielding the original, spanning Hoklo Taiwanese, Mandarin Chinese, and Japanese. He might have refused; he was notoriously skeptical of manhua, deeming the genre insufficiently cerebral. Or he might have done what all grandparents do, which is to indulge their grandchildren in what they vehemently denied their own children — out of love, out of perspective, out of the worn recognition that connection at all is more valuable than critique of its terms.

I would have liked to hear him read aloud from the various languages. I would have paid attention to which phrases — Sensei, tonbo — sounded worn and familiar in his mouth. I would have studied his reaction to the violence depicted, and, if I were brave enough, asked what this kind of suffering meant to him. I would have asked him to sing me the songs invoked throughout the book. Instead, more than two decades after his passing, I can only be grateful for the Heaven and Earth book club this series has facilitated, connecting me and my generation with those that are no longer here, preserving a history that will outlive its last survivors.

And what I cannot share with him, I can share with my peers and lend my small voice in insistence to the publishing industry that such works are urgently necessary. More must be welcomed and championed, and we as Taiwanese Americans must do our part in clamoring that we are here, we will read them, we will be transformed by them, and we will do right by them.

“They are always watching us,” Tsai murmurs of the departed in the final pages, “and also watching to see how we make this country better.”

The Boy from Clearwater speaks to us in our grandparents’ voices; what will we say in return?

Leona Chen is a Taiwanese American community organizer, writer, and speaker committed to building upon the legacy of Taiwanese American elder-activists. Her 2017 debut poetry collection, BOOK OF CORD (Tinfish Press), confronts the shaping of Taiwanese identity through state and family narratives. Passionate about serving the multi-generational Taiwanese diaspora, she believes that through thoughtful political and historical education and meaningful community, we can bridge generational and cultural chasms to empower transnational solidarity, healing, and peace-building. Leona can be found at leona-chen.com and through her bilingual Substack, leonawchen.substack.com.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Taiwan Drawn: Comics and Graphic Novels.’