Written by Yi-Cheng Sun; translated by Yi-Yu Lai.

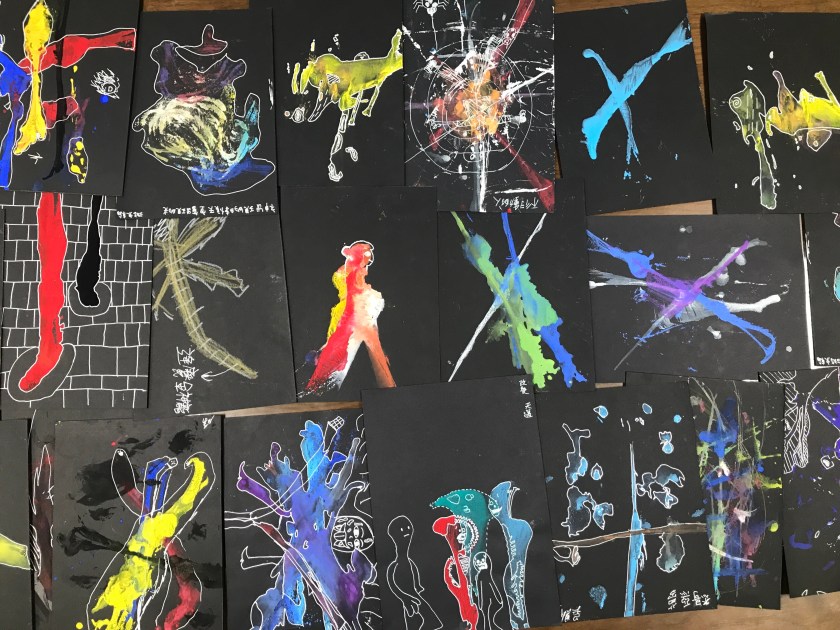

Image credit: Paintings from students, telling their own stories. Photo courtesy of Pin-Hsuan Tseng.

Pin-Hsuan Tseng taught art at Gongliao Junior High School in New Taipei City from 2012 to 2022. Besides being an art teacher, she is well-known for her 2017 initiative called the “Ordering Dishes to End Discrimination” movement. This gentle movement embedded in everyday life aimed to restore the proper name of “Fushan lettuce,” which is commonly referred to as “mainland girl”, with underlying discrimination against females from China. Regarding nationality and gender, Taiwanese media once used “mainland girl” to refer to Chinese prostitutes who arrived illegally in Taiwan, while the smooth appearance of Fushan lettuce was thought to correspond with this image.

Always treating others with respect and consideration, Pin-Hsuan takes inventive action when necessary. She has shaped a not-yet-defined prototype in my mind because I recognise in her both the qualities of an ideal artist and teacher, which combine to form a new paradigm known as the “artist-teacher.” It does not belong to the conventional realm of art education centred on teaching techniques, nor does it belong to the typical pursuit of exhibiting artworks in art museums. Creation and education, both unsettled in fixed forms, intertwine within the fluid relationship between teachers and students, which fluctuates between sensibilities and intellect. Like the rhythm of life, it maintains a breathing and undulating cycle.

Becoming an Artist-Teacher

In 2022, as Pin-Hsuan’s teaching career approached its ten-year mark, she exhibited no signs of the professional weariness that often accompanies a teacher’s tenure. When discussing her childhood experiences with art education, she joyfully shared memories of her elementary school art classes, filled with vibrant and diverse art materials. Besides the common practice of drawing and painting, she recalled working with fabrics, clay, puppetry, and performance. The abundant materials and boundless creative experiences shaped Ping-Hsuan’s sensitivity towards various mediums and broadened her artistic perspective.

Unfortunately, such days did not last long. During high school, Pin-Hsuan, conforming to the norms of art education in Taiwan, began to focus solely on painting in the art studio. Pursuing “painting well” and emphasising “artistic competition” became the most resistant changes in her memory. Upon reflection, she realised that even during her university years, her rebelliousness against traditional artistic creation almost prevented her from graduating.

“Looking back now, even though I was only 22 at the time, it really had a significant impact on me. I wanted to reject that kind of form,” she expressed. According to her memories, the exhibitions she enjoyed were “dynamic” and had a “sense of the body.” The displayed artworks were not required to conform to a specific “artistic style” and didn’t have to be “hung on the wall.” Rejecting the path of becoming the kind of artist institutions expected her to be, Pin-Hsuan turned to education, continuing her alternative form of creation.

During the process of becoming a teacher, just like all aspiring teachers, Pin-Hsuan went through a teaching internship phase. While interning at an urban school, her understanding of her identity as a teacher remained limited to being someone who translates and transforms knowledge for students in a fun way. She never questioned the knowledge presented in textbooks. It wasn’t until after graduating and teaching at Gongliao Junior High School that she experienced an “eye-opening education” from the cultural circumstances of children in a rural region. This sparked profound reflections on knowledge, power, and cultural rights.

She recalled, “I started questioning what the knowledge discourse I had received for over twenty years was. Why is it not accepted in this context? What kind of power do I have to stand in this place? The questioning of power, the questioning of what is ‘primary’ and what is ‘secondary’ in culture, I believe it all began from that time.” During this period, the seeds of an artistic education aligned with social activism were sown.

Having experienced significant disparities between urban and rural educational settings, Pin-Hsuan became more sensitive to the power and authority dynamics in the teaching relationship. She learned how to navigate her role as a teacher and foster relationships with her students. This foundation became crucial in cultivating close connections with her students in the future.

Art Education for the Real World: Artworks as a Pore

In the correspondence and collaborative artworks between Pin-Hsuan and her students, I am always amazed at how the teacher-student relationship can be so intimate and heartfelt. Through multiple interviews, I finally began to unravel the underlying threads. “Penetrability” has always been a concept highly valued by Pin-Hsuan in her teaching. It is a crucial key to establishing connections with her students. The power of penetration is manifested in her classroom through creative acts akin to “pores,” where even the subtle senses, emotions, and thoughts can flow between relationships without the need for language. Thus, even students not adept in verbal expression can use creation to “release the pent-up state, as if there is a pore.”

As an art teacher, Pin-Hsuan’s sensitivity to various mediums helps her create openings that allow the pores to expand. Her simple question to students, “Would you like to try this medium?” becomes a magical incantation in the art classroom, and the medium becomes a switch that “helps children express something they cannot put into words.” In many educational settings, those “things children cannot express” often represent their most authentic and challenging experiences in themselves and in modern society.

In the Pixar film “Soul“, the character “Soul 22”, who struggles to find their Spark in life, wanders into the realm of souls and unexpectedly encounters another protagonist after an accidental death and reincarnation into the soul training program. From Pin-Hsuan’s perspective, in various educational settings in Taiwan, more children lack goals and motivation and are not living up to the expectations of their families and society. Therefore, creating sparks in students’ lives is incredibly important in her vision of art education.

Creation is a “pore” of life, expressing each child’s unique individuality. It can generate positive feedback in their relationships with peers or teachers, offering a sense of accomplishment in career and personal development. Artistic communication is more like a “non-hierarchical dialogue“, providing them with the “right to exist” that exam subjects and knowledge discourses in the education system cannot grant. As long as students create sincerely and express themselves authentically, as a teacher, Pin-Hsuan appreciates, acknowledges, and even praises them from the bottom of her heart. Because in the majority of social circumstances, “believing in oneself and what one can do” is not an easy or taken-for-granted thing.

From rebelling against her art education at the age of 22 to her concern for “Soul 22” after becoming an art educator, in Pin-Hsuan’s journey, creation serves as both an outlet for life and an entrance to rediscovering oneself. It is not only educational but also healing in the process of self-examination and self-awareness. Such experiences are equally present in the life journeys of both teachers and students.

“What Kind of Creation Do You Want to Make?”

As I reflect on Pin-Hsuan’s journey to becoming a teacher, I became curious about where her emphasis on the highly process-oriented and relational aspects of “nurturing” and “healing” comes from. After a brief pause, she began discussing the history of schools: “As a product of the Industrial Revolution, schools have always been a relatively hierarchical existence. One thing I often explore is the ‘timetable.’ Every person in school is constrained by this well-structured timetable, crawling forward, obliged to follow this invisible yet tangible line. If you adhere to it, you will complete the school curriculum. But I think art is like a ‘fork’ in that line. It means using the method of ‘pit-tshe’ (a term in the Taiwanese dialect) to resist institutions and frameworks in a small, microscopic way.

Wanting to truly see and feel the essence of a person, Pin-Hsuan believes that in art education, establishing a fluent and profound emotional connection with students requires the right materials and students engaged in creative coursework and the activation of the teacher’s creative energy and will. No wonder each connection is so profound.

However, in the discourse of art education and teacher training programs in Taiwan, few people ask, “What kind of creation do you want to make as an artist-teacher?” to aspiring art teachers. “In Taiwan’s teacher training programs, in my experience, people who know they want to become teachers are rarely asked this question. Contemporary artists are not often asked this question when engaging in art creation. But once this question is asked, these two domains can intersect somehow.”

In her collaborations with artists, she hoped to convey to them a sense of “We are not just working together; we are working together with a sense of creativity.” By asking, “What kind of creation do you want to make?” she aimed to enter a state of “co-preparation” with the artists, where the artists and herself could engage in a fruitful exchange. Through such interactions, artists often enjoy working with students, and together they discover new approaches to artistic creation at Gongliao Junior High School.

Pin-Hsuan reminisced, “Based on my personal growth experience, art education tends to be marginalised when becoming a professional artist, prioritising artworks and the lurking temptation of considering teaching only when one can’t be an artist. However, there are diverse ways of creation, and the original creation you wanted to pursue can be achieved together, from the preparation beforehand, the implementation process, to the final discussion and outcome. The permeation of relationships through collaboration.” I believe that the ideal intersection of these two domains in Pin-Hsuan’s mind is gradually realised through the form and context of artistic creation that takes the form of teaching.

Yi-Cheng SUN, born in 1990, lives and works in Taipei, Taiwan. She is an independent curator, community contributor and lecturer at NTUH. Her recent interests include cross-disciplinary (Art & Science) collaborative approaches, critical pedagogy, and artist-teacher.

This article was published as part of a special issue on The Artist-Teachers in Taiwan.