Written by Cheng-Ting Wu

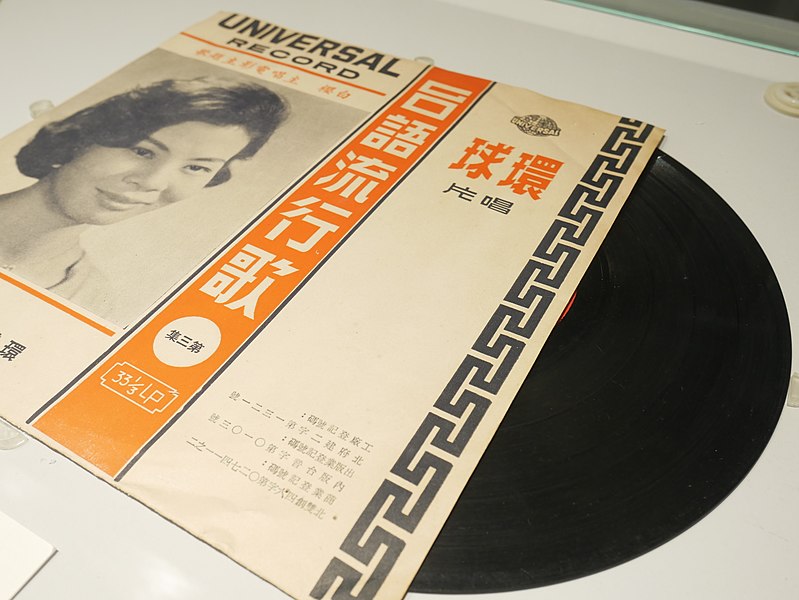

Image credit: 環球台語流行歌唱片 by 氏子 / Wikimedia, license CC-BY-SA-4.0

Imagine you are trying to write a song in Taiwanese Southern Min (hereinafter “Taiwanese”). After creating a soulful melody and heartfelt lyrics, you wonder: How should I write them down? You can choose any of the music notations you prefer for melody, from staff to numbered system. For lyrics, regardless of whether you are a native speaker or a learner of Taiwanese, you also have a choice. This brief article discusses this choice or the different strategies in the history of writing music in Taiwanese.

Taiwanese has been written in various forms throughout the history of Taiwan. From romanisation systems invented by Western missionaries, sinographic characters used by Chinese literati, kana transliteration adopted by Japanese scholars to different schemes proposed by linguists and language activists in the post-martial law era, diverse methods were developed to represent Taiwanese, a language spoken by about twelve million people on the island today. The expression of “how to write Taiwanese” in the language, for example, can be written in romanised alphabet like “tâi-gí án-tsuánn siá,” in sinographic characters like “台語按怎寫,” or in the mixture of both like “台語án-tsuánn寫.”

In the scenario of sinographic writing, characters are adopted to represent Taiwanese instead of Mandarin. To use the example given above, while the two characters “按怎” can be pronounced in Mandarin as “ān-zěn” (Pinyin), they only make sense when pronounced in Taiwanese as “án-tsuánn.” For millions of bilinguals living in today’s Taiwan, determining whether a string of characters is Mandarin or Taiwanese shall not be difficult.

Normally, the choice of writing strategies is related to differences in art forms. While the mixed system of alphabet and characters has dominated the field of Taiwanese literature since the late 1990s, sinographic writing has always been the main method of representing lyrics in Taiwan’s pop music. Despite the superficial continuity, however, the writing of lyrics in Taiwanese, as well as people’s attitude towards the language and its writing, has undergone significant changes in recent decades.

1980s-1990s: Translating Taiwanese into Mandarin

In the 1980s and early 90s, the lyrics of Taiwanese songs were usually represented in the manner of translation. Lim Giong’s (林強) exploratory hit, “Marching Forward” (向前走, 1990), is a great example. In its original music video, while the young, rebellious Lim Giong is passionately singing in Taiwanese, the subtitles are in standard Mandarin, which can only be understood as a translation of the original Taiwanese lyrics. From a linguistic perspective, the MV is more or less equivalent to while the singer performs in Danish, the subtitles give English translation. This convention of translating Taiwanese into Mandarin might come from the Kuomintang’s decades-long policies prioritising Mandarin over local languages. The status of Mandarin as the standard national language was maintained through translation at the expense of linguistic accuracy.

More interestingly, when Rock Records re-uploaded the MV on YouTube in 2012, they added a new version of the lyrics in the description. The updated version contains numerous Taiwanese characters and loyally represents the language’s grammar, forming a remarkable contrast to the subtitles in the original MV. This discrepancy between Marching Forward’s two versions of lyrics epitomises the move away from Mandarin translation in the history of Taiwanese lyric writing.

Early 2000s: Chaos in Sinographic Writing

Around the turn of the twenty-first century, as artists sought to pursue cultural diversity and authenticity in pop music, the Taiwanese’s lack of writing standards caused problems. It was widespread practice that when songwriters and record companies had no idea which characters should be used to represent their lyrics, they improvised based on similarities in meanings or sounds. As a result, several different characters represented a Taiwanese word, and the same character was used to represent unrelated words. For example, the verb beh (want) had been written as “欲” and “要” (both mean “want” in Mandarin) due to semantic proximity and as “麥” and “賣” (both pronounced as “mài” in Mandarin, whose consonant m- is also a bilabial sound like b-) because of phonetic similarity. On the other hand, despite their different meanings, both the preposition kā and the conjunction kah had been represented by the phonetic loan character “甲” (pronounced as “jiǎ” in Mandarin, which shares the same vowel as kah) as in “我會甲你牽條條” [I will hold you tight] in Jody Chiang’s (江蕙) “Wife” (家後, 2001) and in “不願甲你來分開” [I don’t want to be separated from you] in Huang Yee-ling (黃乙玲) and Bingo Kuo’s (郭桂彬) “Sea Waves” (海波浪, 2001). There was neither an official writing standard that everyone could follow nor a one-to-one relationship between words and characters, which led to chaos in the writing of Taiwanese.

2008-Now: Standardising Taiwanese Characters

To improve the chaotic situation, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education announced the “Taiwanese Southern Min recommended characters” (臺灣閩南語推薦用字) around 2008. The project aimed at standardising the writing of Taiwanese by outlining seven hundred “recommended characters” as the official sinographic script. Along with the announcement, the Ministry of Education also complied a list of “Taiwanese Southern Min orthographic characters for Karaoke” (臺灣閩南語卡拉OK正字字表). The list contains about one hundred Taiwanese words that have been written in many different forms, with famous songs as examples. It provides the recommended characters for each word, attempting to put an end to the unregulated state of Taiwanese writing.

It isn’t easy to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the Ministry of Education’s attempt at standardising written Taiwanese. However, In recent years, many musicians have started accepting the official standard. It was reported that when the legendary rockstar Wu Bai (伍佰) was writing his third full Taiwanese album, “Nail Flower” (釘子花, 2017), he verified all the lyrics through the online dictionary published by the Ministry of Education, thereby ensuring every word in the album was written in the orthographic characters recommended by experts. As an established artist, Wu Bai’s meticulous attitude toward his mother tongue undoubtedly inspired younger generations to pay more attention to using the “correct” characters in writing their Taiwanese lyrics.

Reacquiring Mother Tongue as a Second Language

The not-that-young Taiwanese rock trio, Sorry Youth (拍謝少年) also highlights their commitment to their mother tongue. Composing songs exclusively in Taiwanese, Sorry Youth pursues the goal of “[writing] Taiwanese hits that even grandmas and grandpas will approve.” Despite considering Taiwanese as their mother tongue, the band members never shy away from admitting that they are still learning this beautiful language. Instead, they are always willing to share their experiences and methods of learning Taiwanese spoken and written forms. Their relentless passion for writing lyrics in Taiwanese properly echoes a lot of young Taiwanese people who are also on their journey of “reacquiring” the languages their mothers or grandmothers speak. The case of Sorry Youth represents the phenomenon of “mother tongue as a second language” in today’s Taiwanese society, and their motivational story reflects society’s positive encouragement towards mother tongue music.

Conclusion

To end this article, I would like to discuss the word “拍謝” (Mandarin: pāi-xiè) in Sorry Youth’s band name. For a long time, the two characters have been used to represent the Taiwanese exclamation pháinn-sè (sorry) based on phonetic similarity. However, according to the Ministry of Education’s online dictionary, the recommended characters for pháinn-sè are “歹勢.” This gives rise to the question: Is “拍謝” the “wrong” way of writing the word pháinn-sè? Should everyone always write Taiwanese with the “correct” characters? Given the unpopularity of the recommended characters and the dominant status of Mandarin in Taiwan, writing Taiwanese in Mandarin transliteration might be easier to understand for people who have not learned the official characters. That is to say, writing Taiwanese sometimes turns out to be a trade-off between linguistic precision and accessibility. Your choice thus matters. It is a challenge to decide which character or writing system to use in various situations, but every choice contributes to the search for a shared script for Taiwanese.

This article was published as part of a special issue on Pop Music, Languages, and Cultural Identities in Taiwan.