Written by Aoife Cantrill.

Image credit: Screenshot from the National Book Foundation website.

In its special issue on ‘Taiwanese Literature In/And The World’, published last year, Taiwan Insight reflected on the relationship between Taiwan literature and world literature. Responding in part to the publication of several recent landmark books on the topic (including Taiwanese Literature as World Literature and The Making of Sinophone Literature as World Literature), the featured articles considered cross-border plots and alternate histories, queer readings of historical atrocity, and Taiwanese contributions to world literary theory in the spirit of ‘intersectionality’ and ‘relationality’. Across this special issue, there was a resounding endorsement of the view Chia-rong Wu and Ming-ju Fan put forward in their 2023 edited volume Taiwan Literature in the Twenty-first Century: that Taiwan literature post-2000 is defined by a ‘translocal perspective’. Fan and Wu suggest that Taiwanese writers today think reflexively in multitudes, as their literature engages with stylistic and thematic approaches from elsewhere whilst remaining tied to a distinctive Taiwanese point of view. This textual border-crossing recurs in the writing of authors featured in Taiwan Literature in the Twenty-first Century, whether that be Kevin Chen, whose work looks back at Taiwan from abroad, writers in the diaspora like Shawna Yang Ryan, or writers in Taiwan like Liglave A-wu who incorporate activism on gender and sexuality into their work.

Translation – whether cultural or linguistic – makes a significant contribution to the work of this more recent generation of writers. Jessica Lee’s memoir Two Trees Make A Forest, which tells the story of the author’s reconnection with Taiwan through accounts of the island’s natural landscape, foregrounds translation in its opening page with a deconstruction of the English word ‘island’, noting how it shares its linguistic roots with ‘the German ‘aue’, from the Latin ‘aqua’, meaning ‘water’’ whereas the Chinese term 島 (dao) ‘knows nothing of water’ as it is made from the words mountain (山 shan) and bird (鳥 niao). Though Lee’s text uses translation to serve its specific perspective as a biographical piece of nature writing, its engagement with the comparison of language – and its history – as a method of storytelling is a strategy with deep roots within Taiwan literature. At the same time, while literary transnationalism might be more explicit in contemporary texts, Wen-chi Li and Pei-yin Lin have demonstrated that a ‘translocal’ approach appears in some of the earliest examples of Taiwan literature through the works of authors, including Wei Ching-te and Lōa Hô who took inspiration in the 1910s from French writers including Maurice LeBlanc and Anatole France.

Given how border-crossing has been a component of Taiwan’s textual culture since at least the 1910s and how linguistic diversity was the target of violent censorship and erasure under both Japanese colonial rule and the forty years of KMT martial law that followed, it is perhaps unsurprising that the act of translating, and the figure of the translator, have recurred in texts published following the end of martial law in 1987. Wu and Fan include one such text in their overview of Taiwan literature after the millennium, with Fan describing Lai Hsiang-yin’s 2017 short story collection The Translator (翻譯者 Fanyizhe) as ‘the greatest political fiction to depict Taiwan’s history since the lifting of martial law’. The final story in the collection (also titled “The Translator”) is the most explicitly linked to translation, as it depicts a woman attempting to translate the writings of her parents, who had taken part in Taiwan’s pro-democracy movement prior to 1987. The protagonist’s struggle to undertake this act of translation – and the discomfort of finding her parents’ words almost untranslatable – works as an effective metaphor for the difficult passage of historical memory in Taiwan after successive decades of colonial and then authoritarian governance. Over the duration of the story, the protagonist confronts the empty promise of postcolonial translation, which, as Michael Cronin points out, often substitutes resolution for further complication.

Translation, historical memory and its distortion are also central themes in Chu T’ien-hsin’s 1990 short story “Long Ago There Lived Urashima Tarō” (從前從前有個浦島太郎 Congqian, congqian you ge Pudao Tailang). The story adapts a classic Japanese fairy-tale about a child named Tarō who travels to the bottom of the ocean on the back of a turtle through the figure of a neurotic Japanese-Chinese translator and former political prisoner living in Taiwan during the White Terror. This translator, a man named Li Jiazheng, is an unlikeable figure who is driven by his fear of re-arrest to write letters of denunciation obsessively. He recalls his mother telling him the story of Urashima Tarō as a child and his anxiety at the story’s ending, where the child returns to land after spending what seems to him to have been only a few days in the water only to discover that, in earthly time, decades have passed. He is now an elderly man whose life is behind him. In Chu’s retelling, it is the sight of his unsent denunciation letters – the externalisation of Li’s paranoia – that triggers a similar horror as time passing. Li’s work as a translator receives only passing mention, but his bilingual existence serves only to intensify his isolation in a police state that cuts him off from the rest of the world as though he were living underwater. The writer’s block faced by the protagonist in Lai’s “The Translator” reproduces in miniature the constriction of Li Jiazheng’s linguistic identity by the state, which amounts to a continual infringement on both his professional and personal identity.

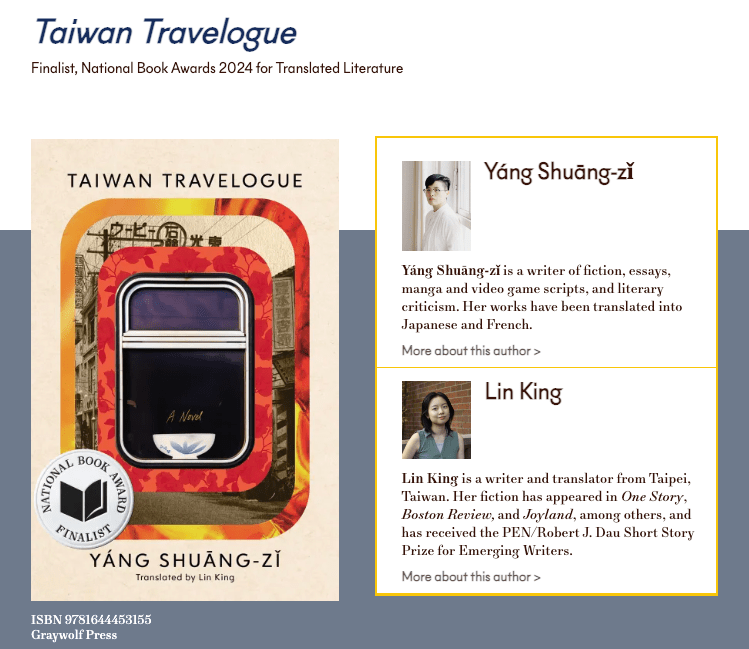

More recently, Yang Shuang-zi’s Taiwan Travelogue (臺灣漫遊錄 Taiwan manyou lu) has taken a different approach to representing translation from the Japanese colonial era to the present day. Published in 2020, Travelogue is a fake translation of a fictional travelogue written by a Japanese author named Aoyama Chizuko, who travelled to Taiwan in 1938 for a book tour. Translation is central to the plot: the novel focuses on Chizuko’s relationship with her Taiwanese interpreter, Chizuru, as the two women travel around the island together, visiting local sites and eating a selection of delicacies. A romance of sorts develops between the two women that, in the end, they cannot realise – in part due to their respective status within the hierarchy of colonial society. Yang presents this story to the reader as a retranslation of a lost manuscript with a history marked not only by the colonial era in which it was first published but also by the restrictive linguistic and cultural policies that prevented its full publication in translation under martial law. The final portions of the novel (a postscript by Chizuru’s daughter and a translator’s note by Yang herself) provide the reader with this additional history, as well as a commentary on the challenges to uncensored translation throughout much of Taiwan’s twentieth century. The revelation that Travelogue is, in fact, a fake translation amplifies the novel’s observations on the relationship between language and power, with the takeaway message being that translation can both reinforce the architecture of colonial hierarchy and serve as a tool for its deconstruction.

In their own ways, each of these stories is generational: Lai Hsiang-yin’s translator works with her parent’s words, Chu T’ien-hsin’s mother (Liu Musha) was a celebrated Japanese-Chinese translator in Taiwan, and the structure of Yang Shuang-zi’s novel provides the vantage point of a new generation looking back on the lifetime of their grandparents after decades of historical repression. In this sense, the act of translating each of these texts can appear as an introspective exercise in historical recovery. Despite this, both “Long, Long Ago” and Taiwan Travelogue have been translated into other languages, with the English translation of Taiwan Travelogue by Lin King receiving particular recognition this year through its shortlisting for the National Book Award in the United States. Where most societies have an obvious reliance on translation to tell their stories to others, Taiwan literature also uses translation to tell its own story back to itself, a mode of writing defined by linguistic and temporal multiplicity.

Aoife Cantrill is a Junior Research Fellow at Queen’s College, University of Oxford. Her research looks at textual culture in the Sinophone territories of the Japanese Empire, with a particular focus on gender, materiality, and postcolonial translation. She is currently completing her first monograph, which looks at women’s writing, gendered citizenship, and translation politics in Taiwan from 1930 to the present day.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Global Taiwan Literature’.