Written by Tun-Jung Kuo and Li-Ting Chang.

Image credit: authors.

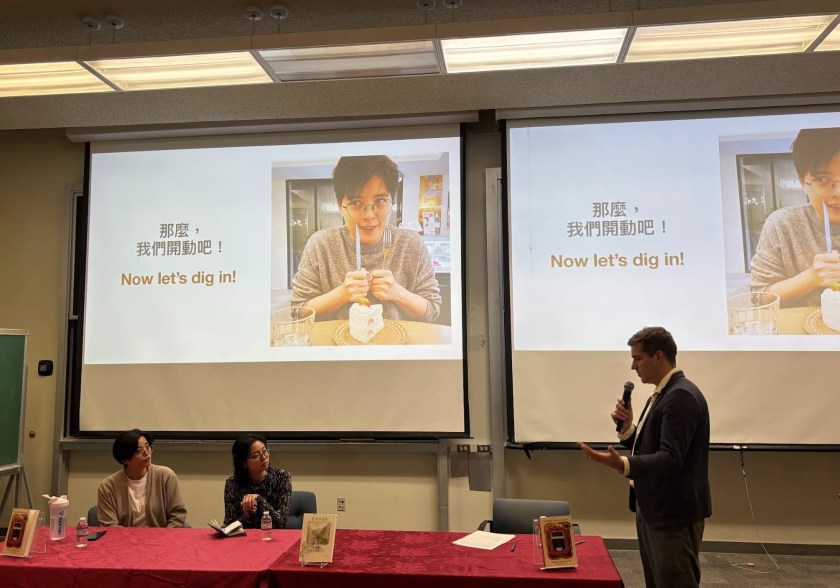

On a bright afternoon with a cosy, gentle breeze, the Center for Taiwan Studies (CTS) at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) warmly welcomed Yáng Shuāng-zǐ and King Lin for a discussion of their recently acclaimed novel, Taiwan Travelogue (臺灣漫遊錄). Held on February 25, 2025, this book talk received support from the Ministry of Culture in Taiwan, the Taiwan Academy in Los Angeles, and UCSB Translation Studies. It was one of several stops on the book tour, which included visits to other campuses in Southern California, such as UCLA, UC Irvine, and Chapman University. Taiwan Travelogue and its book tour marked a major milestone in the development of Taiwanese literature by offering a unique narrative of Taiwan’s history and culture and elevating the visibility of this vibrant island. At UCSB, Yáng and King engaged in an intellectually rich and inspiring conversation with the moderator, Professor Thomas Mazanec, who specialises in premodern Chinese literature, digital humanities, and translation studies. The audience, comprising faculty members, graduate students, and undergraduates, expressed enthusiasm for the novel, posed thoughtful questions, and shared their reading experiences and critical reflections. This engaging event deepened participants’ understanding of Taiwan’s diverse ethnic, linguistic, and culinary traditions and fostered an ongoing dialogue about Taiwanese literary culture in North America.

Food plays a central role in Taiwan Travelogue, as the novel weaves Taiwanese cuisines, such as kue-tsi (roasted seeds), savoury cakes, shaved ice, and banquet dishes, into its literary narrative of the island’s history and culture. Structurally, each chapter is titled after a distinct Taiwanese dish. The depiction of dishes in the book resembles the portrayal of food in one of the greatest Chinese novels, Dream of the Red Chamber. Both works vividly and meticulously describe every aspect of ingredient selection, preparation, pairing, and cooking, along with the sensory experiences of smell, texture, and taste. Additionally, both accentuate food not only as a culinary element but also as a reflection of cultural values and historical contexts. In Taiwan Travelogue, food reveals its deep connection with a wide range of Taiwanese social customs, from daily family meals to major celebrations. By embedding culinary traditions within its storytelling, the novel presents a more appealing, palatable, and mouthwatering version of Taiwanese history.

The novel highlights the “localisation” and “glocalisation” of Taiwanese food, reflecting the rich, heterogeneous characteristics of Taiwan’s food culture and its cultural history. The novel’s protagonist, Aoyama Chizuko, travels from Nagasaki, Japan, to Taiwan and explores various dishes throughout her journey, from traditional Taiwanese dishes like Braised Minced Pork to Japanese-influenced foods such as sashimi, curry, and sukiyaki. In Chapter Five, titled Bah-Sò/Braised Minced Pork, Chi-chan, a Taiwanese character, introduces iconic Taiwanese dishes, lóh-bah-pn̄g (滷肉飯) and bah-sò pn̄g (肉臊飯), to Chizuko. Chi-chan explains two kinds of rice (pn̄g) commonly used in these cuisines: hōrai rice (蓬萊米) and zairai rice (在來米). Hōrai rice is a type of Japanese rice modified to grow better in Taiwan’s climate, whereas zairai rice refers to native Taiwanese rice (Taiwan Travelogue, footnote 14, 113). As the text reads:

“When it comes to both lóh-bah-pn̄g and bah-sò pn̄g,” she said, “the other main character is the pn̄g—the rice. The Island’s traditional long-grained zairai rice is delicious, and one can also stream it together with glutinous rice for a different texture. Short-grained hōrai rice has more elasticity and can better absorb the juice from the meat, and nowadays, both lóh-bah-pn̄g and bah-sò pn̄g vendors use hōrai rice.” (Taiwan Travelogue, 112-113)

The passage describes rice, the soul of the classic Taiwanese street foods lóh-bah-pn̄g and bah-sò pn̄g, in great detail by analysing the appearances, flavours, and textures of hōrai rice and zairai rice. The widespread use of “foreign” hōrai rice in Taiwanese cuisine during Chi-chan’s time underscores the impact of Japanese colonisation on everyday activities like eating. It exemplifies the localisation of Japanese ingredients on the island. Similarly, many foods in Taiwan originate from abroad but become integral to local cuisine through a dynamic process of appropriation and transformation. What deserves critical attention, however, is not the origin of these foods but Taiwan’s local reception and adaptation of foreign influences. This focus allows us to recount the history of Taiwanese food culture from a Taiwan-centric perspective and asserts the island’s subjectivity. During the book talk, Yáng insightfully parallels this view with Taiwanese self-identification. As she articulates, regardless of where we, as Taiwanese people, come from originally, what matters is how we identify ourselves.

Taiwan Travelogue and its book talk enhance our understanding of how food helps construct collective memories and evokes nostalgic feelings. In the chapter Sukiyaki/Beef and Vegetable Hotpot of the novel, Chi-chan underlines the vital role clam noodles played in her childhood. Chi-chan recalls the noodles, generally considered “somewhere between street food and home cooking”: “The taste of clam noodles is deeply etched into my childhood, you see” (Taiwan Travelogue, 182). Just as Chi-chan’s emotional attachment to the noodles, Yáng shares how a lesser-known Taiwanese dish introduced in the novel, Muâ-ínn (jute), occupies a special place in her heart during the talk. Jute is a local dish traditionally grown in central Taiwan and often used to make soup. In the Japanese colonial period, people cultivated jute for its fibres and processed them into burlap sacks. While this dish may not come to mind as representative of Taiwanese cuisine, eating a bowl of jute soup is an everyday activity and lived experience shared by many from Taichung, including Yáng, who was born and raised in this city. As she describes in the talk: “Jute tastes a little bit bitter, and I don’t even enjoy it that much.” Her words, combined with the novel’s vivid portrayal of this dish’s flavour and how it is cooked, enable us, as the audience, many of whom have never tried it, to imagine the taste of this Taichung specialty. The case of jute encapsulates Yáng’s interpretation of home, creates her and other Taichungnese’s shared memories, and solidifies their cultural identity. Furthermore, her concern that this dish might one day disappear motivates her to document the food, its taste, and its cultural significance in literary form. This way, Taiwan Travelogue not only preserves jute and its related memories but also transforms it into a literary art that sparks readers’ curiosity and broadens their knowledge of Taiwanese food culture.

Yáng seeks to bridge the gap in Taiwan’s history under Japanese rule through Taiwan Travelogue as historical fiction. In stark contrast to the official historical accounts, which are predominantly male-centred, the novel is narrated from Chizuko’s point of view, a female perspective that often goes unheard. Moreover, the story emphasises details of everyday life, such as daily food arrangements and lively dialogue between Chizuko and Chi-chan, capturing fleeting, transient, and fragmentary moments. By doing so, the novel brings readers closer to the lived experience in colonial Taiwan and enriches official historical narratives that focus solely on pivotal incidents and dramatic changes.

This story, which centres on women, demonstrates the nuanced relationship between the coloniser and the colonised through the complex interpersonal dynamics between Chizuko and Chi-chan. Rather than depicting the coloniser as a cruel and monstrous figure, Taiwan Travelogue presents Chizuko as a generous, genuine, and open-minded individual who attempts to explore Taiwanese local culture. However, her curiosity and appreciation for Taiwan and its food inevitably fall into the pitfall of romanticising colonial violence and assimilation. For example, when she proudly praises Japan’s efforts in improving Taiwan’s fishery industry and gives credit to the Japanese empire for the birth of Taiwan’s chikuwa (黑輪), she overlooks that the empire’s intervention also disrupts local culinary traditions (Taiwan Travelogue, 241-245). This instance exposes the subconscious discriminatory attitudes Chizuko, as a Japanese “Mainlander” (Naichi Japanese), holds toward Taiwanese “Islanders.” Her blind spot and ignorance of the oppression that colonised subjects struggle with hinder her relationship with Chi-chan. Yet, the novel grants Chizuko an opportunity to redeem herself toward the end, when she and Chi-chan drift apart and a Taiwan-born Japanese, Mishima, criticises her “intellectual arrogance” (Taiwan Travelogue, 245). For the first time, she realises her constant normalisation and naturalisation of colonial influences after Mishima pointedly declares: “There is nothing in the world more difficult to refuse than self-righteous goodwill” (Taiwan Travelogue, 247). Chizuko eventually admits her arrogance in a moment of self-critique: “I am but a proud, foolish, and despicable brute!” (Taiwan Travelogue, 249).

Furthermore, the story showcases the intricate psyche of Taiwanese “Islanders” through Chi-chan. Throughout the novel, she continually navigates a tension between the frustration of Chizuko’s inconsiderate comments and her gratitude for this Japanese individual’s sincerity and kind heart. The characterisation of Chizuko and Chi-chan challenges a binary conceptualisation of the colonisers as pure evil and the colonised as powerless victims, encouraging a more critical inquiry into the hierarchical relationship and power dynamics that structure colonial relations.

Trains and railroads, as key motifs in the novel, effectively shorten travel time and dissolve spatial barriers in colonial Taiwan, which makes possible the intermingling of different ethnic groups across this island. To some extent, Taiwan Travelogue, alongside its English translation and book talk, invites us as contemporary readers to board a train made of written words and travel back in time. On this literary journey, we savour a unique narrative of Taiwan’s colonial history, one that revolves around mouthwatering Taiwanese foods and amplifies female voices.

Tun-Jung Kuo is a PhD student in Educational Foundations at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She works with the Center for Taiwan Studies at UC Santa Barbara and has closely collaborated with the East-West Center and TECO (Taipei Economic & Cultural Office). Additionally, her past experiences in international education include supporting the Chinese Flagship Program at UH Manoa and assisting local host families for international students in Hawaii. Kuo’s research focuses on East Asian education, Confucian Heritage Culture learners, organisational development, and intercultural competence.

Li-Ting Chang is a PhD candidate in East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at UC Santa Barbara. Her research interests include Chinese literature, print media, affect theories, gender studies, Taiwan studies, Sinophone studies, and popular culture. Her dissertation project, “Dear Darling: Love Letters as a New Cultural Sensation in Early 20th Century China,” explores the interplay between the concept of romantic sentiment and the love letter as both a literary genre and an everyday practice. She is also an advisory member of the UCSB Center for Taiwan Studies and one of the organisers of the Taiwan Studies Workshop. From 2023 to 2024, she served as a program commissioner for the North American Taiwan Studies Association (NATSA).

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Mapping Taiwan: Literary Paths and Real Journeys‘.