Written by Elissa Hunter-Dorans.

Image credit: Scottish Peasant Women by James Ward.

Lāu-lâng m ̄ kóng-kó, siàu-liân m ̄-bat pó

If old people don’t tell stories, young people won’t know what matters. Taiwanese proverb.

Mura h-innis seann daoine sgeulachdan, cha bhi fios aig daoine òga air dè tha cudromach. Seanfhacal Taidh-Bhànach.

Every culture, and its language, has a word for grandmother; but in the Taiwanese (a-má) and Gaelic (seanmhair) of Tâigael, she comes to embody an archive of the languages themselves. When I first joined the Tâigael project team, I expected to find my focus drawn simply to the age-old traps and treats of the translation of fiction across languages. The lesson to be learned first-hand through the project seemed clear: to observe how intricacies can be changed, lost, or even surprisingly strengthened when a story about something culturally specific sails through a chain of linguistic hands. As I am more familiar with writing poetry than prose, I expected to see demonstrated the instability of poetic phrasing: how metaphors may get warped, how syntax might become clunky, and how the meaning of cultural idioms might be rendered muddy. I anticipated, wrongly, that my focus would be on loss. What I did not expect was to discover an unusual kinship between two cultures that are usually thought of as distant and fairly unrelated – Gaelic Scotland and Taiwan.

I learned about the countless similarities between the histories of the languages of Gaelic and Taiwanese; political linguistic repression and contemporary revival, to name a few. As the Tâigael team worked together across time zones to read and translate all the stories into all the languages that link us, I began to realise that this shared history of oppression might have a perhaps unconscious effect on the themes and characters chosen by those writing in these languages today. In many of the stories, both from Scotland and Taiwan, I noticed an unexpected pattern of theme – the maternal. Whether this be literal, with stories mentioning the traditional guiding presence of a grandmother; or subtle, with a woman tending to a sheep as her own; or even surreal – a religion manifesting in the form of a wise female guest at a family party – these motifs emerged independently in our Gaelic and Taiwanese writers.

This blog post reflects on how the maternal emerges as a shared literary figure with room for much imaginative potential across the contemporary psyches of these two marginalised languages. It suggests that the recurrence of maternal (and grandmaternal) imagery is shaped by the importance of the oral traditions of both cultures, as well as the personal memory evoked, and that the intimacy assumed by writing in these marginalised languages makes the languages almost familial themselves. I explore how these stories, while all very personal and culturally specific to the writers, also seem inextricably linked with the global concept of the “mother tongue”, upon which this very project was conceived. It is a term that is usually understood as “native language” but which, in these contexts, takes on a much more literal and metaphorical tenderness that binds marginalised languages to our own familial origins and legacies, and demands generational reflection. Hers is an unmoving voice that nurtures, protects, and passes on these languages and customs down to future speakers. Today, when perhaps the flesh-and-blood mother figure that traditionally passes the language down is absent, the language itself therefore has the potential to become as maternal.

In Scotland, Gaelic was once the majority language of much of the Highlands and Islands but faced centuries of political marginalisation. Children were punished in schools for speaking it, and parents were discouraged from teaching it to their children, in the hopes that this would allow them to achieve social and economic mobility for the generations to come. The result was a tear in its linguistic and cultural inheritance. Taiwanese languages such as Hokkien, Hakka, and other Indigenous languages went through similar oppression. Under Japanese colonial rule, and even later under the Kuomintang’s Mandarin-only policies in schools, children were also punished for speaking local languages. Similarly, Taiwanese parents often adopted the dominant language in their child-rearing, due to perceived future disadvantages for their children if they were to be raised speaking another language.

In both countries, this disruption often occurred most devastatingly in the most intimate space, the home. So, in all of our Tâigael stories, the metaphor becomes especially literal. Mothers and grandmothers have often been the last speakers – the ones who keep the language alive in domestic spaces when it is made to disappear from schools, workplaces, and general public life. The result is that in both Gaelic and Taiwanese contexts, the maternal metaphors carry a hope of an alternative memory of linguistic continuity, when that continuity has, in reality, been broken. With loss of language, there is an inherent loss of memory, place and family. So, it is only logical that young learners of these languages can find a metaphorical elder in the very language itself, with proverbs and teachings embedded into daily speech. So, to me, when we depicted maternal figures in Tâigael, we did not simply choose a common literary theme but explored a metaphor that reflects our language’s historic and current survival. In my own family, this is what happened. When I learned Gaelic as a young teenager and entered spaces where the language was spoken, I was often asked who my grandmother or great-grandmother was to provide a sense of legitimacy to my speaking Gaelic. Due to this lack of intergenerational transmission, I don’t know the name of my most recent Gaelic-speaking relative, but I do know that she lived only two “grandmothers” ago! It is also true that, just like a mother can teach us about origin, re-learning and writing in a “mother tongue” can help us better connect with the stories and beliefs of the places and people we come from, whether that language be to us truly maternal, or great-grand-maternal. To call a language “mother” is poetic in itself, and so is the fact that this is a phrase that drifts across most languages and borders, globally.

…cànan màthaireal, bó-gí, cainnt do mhàthair…

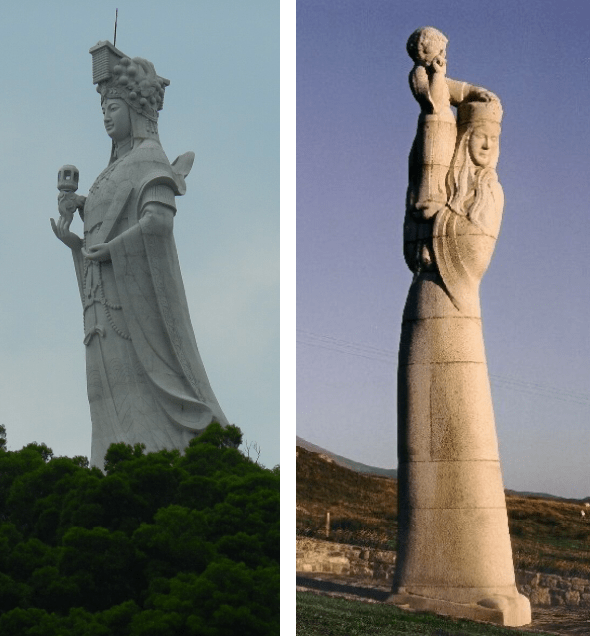

In both my story and Naomi’s, the literal grandmother figure was connected to the preservation of local religion. In an increasingly secularised world, the distance of two or more generations that is implied by “grandmother” evokes both the mystery and wisdom of a recently bygone era, and so by associating religion with grandmothers, young writers can demystify these beliefs. In mine, the personified Presbyterian Free Church of Scotland was jeered at, feared, or ignored by many characters, but waited upon by the main character’s grandmother – symbolising the unfaltering respect for the church among the older generations in Gaelic Scotland, despite the changing world around them. In Naomi’s, the main character’s grandmother brings her to a temple to see the sea goddess Mazu for healing purposes, a god also known as Ma-tsu, which means “maternal ancestor”. She is also called “grandmother”.

Writing in a marginalised language has an inherent intimacy assumed. This is a thought I first heard from the Gaelic writer Niall O’ Gallagher and relates to Lauren Berlant’s theory of “intimate publics” (2008). Niall said that since Gaelic (and in our case, also Taiwanese) is addressed to a smaller readership, we might imagine it as a close-knit one, perhaps almost familial. We are writing for friends, family, and the beloved. This, whether consciously or not, changes the permissions we give ourselves for the content of our writing – unlike in a global language like English, where the audience is vast, with therefore censoring anonymity. In light of these ideas, the metaphor of the maternal becomes even more fitting. Writing in Gaelic or Taiwanese can be to some like speaking to family: intimate, safe, knowing. It can assume a mutually conscious relationship between the writer and the reader.

Of course, the role of mothers in language acquisition in Gaelic and Taiwanese has changed. In many situations, children (like myself) now grow up without hearing the language at home and may choose to learn it independently, through school or other cultural initiatives. Mothers and grandmothers may no longer be the primary transmitters of speech. In this context, the bodies of literature that have preserved these languages take on new maternal roles. Stories, poems, and songs become the vessels for passing down linguistic nuance, nurturing the language’s chest of riches for future speakers, like a surrogate mother. This is simultaneously a grave loss and a world of possibility. It is a loss because no written word can replace the warmth of a child hearing a language and uttering its first words in it from the comfort of a grandmother’s lap. But it is also a possibility, because literature can reach beyond this limited home space to connect displaced communities across the seas and borders of the world, allowing for immense creative potential and the birth of new forms of intimacy between speakers.

Engaging with the historical literature and music of these languages “grandmothers” us too, giving us the knowledge to deviate from the standardised vocabularies and accents taught in schools and other institutions. Elie, a good friend of mine from Brittany, read me a page of the Gaelic Bible with an accent that was hauntingly true to archived recordings of speakers; an accent he had picked up from sitting attentively at the knee of Gaelic songs. In Naomi’s story for Tâigael, the main character’s grandmother teases (and aides) her accent in Taiwanese, but is extremely proud to see her writing creatively in the language. Literature, both new and traditional, preserves for us how the language is really spoken, colloquially and regionally, much more than textbooks and exams can. The creation of new literature in minority languages is therefore not only creative but crucially generative, and increasingly essential as the familial practice of oral storytelling dwindles. Like a maternal voice, it protects, teaches, and guides us as new speakers of these tongues. And, in projects like Tâigael, literature creates unpredictable bonds of kinship across cultures, as it reminds us that even in translation, the honour we give to our mothers, and mother tongues, is universal – can be carried across in words.

Elissa Hunter-Dorans (elissa.ldhd@gmail.com) is an Edinburgh-based writer and artist from the Highlands, writing in Gaelic and English. She was the Scottish Poetry Library’s first Next Generation Young Makar for Gaelic poetry, and she has performed at StAnza, The Edinburgh Fringe, and Push the Boat Out. She is the Gaelic editor for The Poets’ Republic by Drunk Muse Press and was the Gaelic judge of the 2025 Wigtown Poetry Prizes. She has a fascination with religious and folk visual culture and is currently studying History of Art at the University of Edinburgh.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic‘.