Written by Chien-Ping Liu

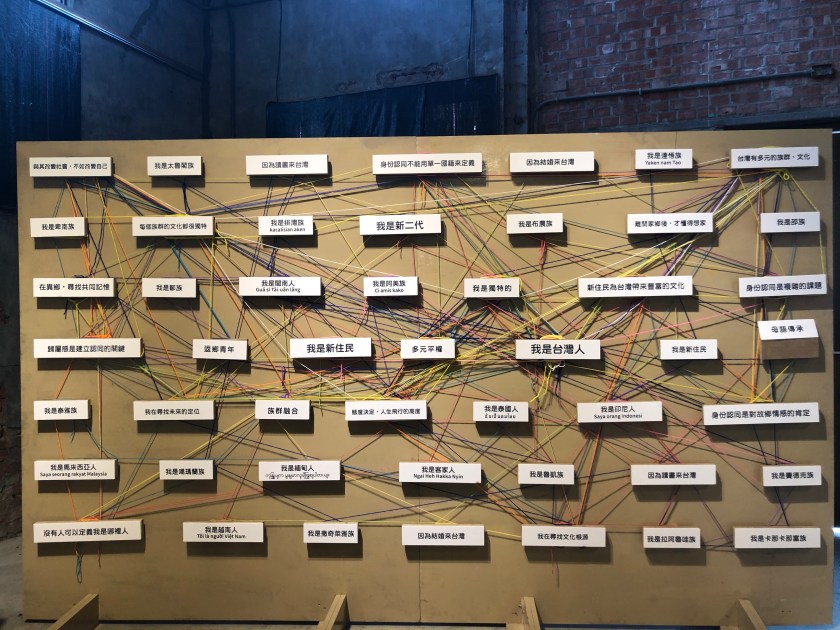

Image credit: Provided by the author. At the 2020 exhibition “Stories of the New Second Generation after Migration”, visitors used strands of yarn to interweave slogans expressing diverse forms of identity and belonging.

The wave of transnational marriages that began in the late 1990s significantly reshaped Taiwan’s demographic landscape. Beyond Taiwan, other post–Cold War developmental states in Asia—such as Japan and South Korea—also faced demographic crises in the late 1990s amid growing affluence, including high sex ratios, population ageing, declining birth rates, and imbalances in industrial labour. While these societies successively opened to migrant workers to alleviate social and economic needs, transnational marriages within the region also increased significantly (Bélanger 2010). Under the logic of nation-state reproduction, marriage migrants were the first to be incorporated into citizenship regimes, giving rise to a gendered pattern of migration across East Asia (Bélanger, Lee and Wang 2010; Chung 2020).

According to Taiwan’s National Immigration Agency (NIA), new immigrants (新住民) are foreign spouses who have settled through marriage or immigration since 1987. Transnational marriages accounted for 14% of all unions in 1998 and peaked at 28% in 2003 before stabilising at around 21,000 per year. As of 2025, Taiwan hosts about 600,000 new immigrants, roughly 2.5% of its population.

In the early 2000s, mainstream discourse portrayed marriage migrants—especially from China and Southeast Asia—as “economically motivated” or “disloyal”, and their maternal competence was questioned; this stigma extended to their children, fuelling anxieties about a supposed decline in population quality (Hsia 2007). Policies during this period emphasised control and supervision over inclusion. The 2003 overseas marriage interview mechanism verified “authentic” marriages and reduced transnational unions (Control Yuan’s Investigation report 2012). Residency and naturalisation depended on marital stability and “moral conduct”, reinforcing patriarchal governance. Programs in maternal health, childcare, and language education were framed as tools to “enhance domestic competence”, reflecting a paternalistic and disciplinary approach to migration governance.

The children of marriage migrants were labelled the “New Children of Taiwan” (新台灣之子). The term perpetuated a patrilineal logic of ethnic classification, framing them as transformed yet assimilable offspring of native Taiwanese, rather than as children of new Taiwanese (immigrant) families. In the past decade, this framing shifted: policy and social discourse redefined them as the “New Second Generation” (新二代), acknowledging immigrant heritage and cross-cultural potential (Lan 2019). Second-generation immigrants have gone from being seen as a social problem to becoming a national talent asset (Hsia 2023). Based on the annual statistics on “births by parental nationality” compiled by Taiwan’s Ministry of the Interior (MOI) since 1998, it is estimated that the number of Taiwanese residents with at least one immigrant parent currently exceeds 500,000. The Ministry of the Interior estimates that by 2030, 13.5% of Taiwanese aged 25 will be children of new immigrants, according to the Report on the Living Needs of New Immigrants in 2024.

The phenomenon of East Asian countries using multicultural terminology in their immigrant integration policies deserves attention. The context in which multiculturalism is practised in these policy discourses has influenced the logic of immigration governance and the new ethnic landscape of host countries after globalisation (Iwabuchi, Kim, and Hsia 2016).

Launched in 2016, the Tsai Ing-wen administration’s New Southbound Policy is often regarded as a watershed moment marking the policy shift concerning the second generation of marriage migrants. It reflects how the market logic of regional economic globalisation and changing geopolitical dynamics in East Asia have turned Southeast Asia into a strategic lever for Taiwan in countering China, thereby motivating the state to highlight intergenerational cultural transmission among Southeast Asian marriage-migrant families (Lan 2019).

However, as Hsia’s research has shown, grassroots advocacy movements led by immigrant women themselves have been a driving force behind Taiwan’s evolving immigrant integration policies (Hsia 2010). Chung’s comparative research further demonstrates that in East Asian countries (Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan), immigration governance—including citizenship regimes and migration policies—has not been a purely top-down process of national incorporation. In the absence of a comprehensive state-led integration framework, civil society actors have played a pivotal role in responding to the challenges of immigration. The resulting modes of immigrant integration in East Asia are therefore products of the interaction between migrants and their societies’ civic legacies (Chung 2020).

The tensions between civil-society advocacy and state developmental strategy have long shaped the multicultural discourse of immigrant integration in Taiwan. This dual dynamic simultaneously enables inclusion and generates new forms of exclusion.

Bottom-up Multiculturalism: The Mother and Child in Immigrant Advocacy Movements

In 2003, Taiwan’s immigrant social movement coalesced in the formation of the Alliance for Human Rights Legislation for Immigrants and Migrants (AHRLIM). The alliance brought together several key groups: the TransAsia Sisters Association in Taiwan (TASAT), composed primarily of marriage migrants; The Awakening Foundation, representing women’s rights activists; the Serve the People Association (SPA), which engaged in migrant labour advocacy; and the Taiwan Association for Human Rights (TAHR), among others (Hsia 2009).

Chung (2020) argues that reforms in immigrant integration gain traction only when civil-society actors put them on the agenda and that Taiwan’s democratic civic legacies shape migrants’ strategies toward the state. Hsia’s (2009) research on AHRLIM identifies two features: non-immigrant advocates acted as bridges linking migrant demands to civil-society values, and the alliance centred immigrant women’s agency and subjectivity. Drawing on professional expertise in law, academia, and NGOs, these allies translated civic ideals into advocacy frames that resonated publicly. Marriage migrants’ experiences were dramatised through street theatre and press events where women spoke as protagonists, making their voices visible in the media and strengthening collective confidence. Second-generation children sometimes appeared beside their mothers or served as symbolic figures of intergenerational inclusion.

One of AHRLIM’s most emblematic actions occurred in July 2004, after Deputy Education Minister Chou Tsan-Te urged local officials to “advise foreign and Mainland spouses to practice birth control.” Six days later, AHRLIM staged a protest. Media coverage focused on a four-year-old girl wearing a sign that read, “I am not developmentally delayed.” Her silent presence embodied innocence and injustice, visualising the stigma imposed on immigrant families. A grown-up child of a marriage migrant also addressed the rally, presenting flowers to his mother and other women to honour their perseverance and to refute stereotypes of poor parenting. The protest slogan—“We are not here just to give birth!”—captured its strategic message: marriage-migrant women were not outsiders but Taiwanese mothers.

Beyond protest, immigrant advocates effectively challenged nationalist discourse by invoking the civic frameworks of ethnic equality and respect for multiculturalism that had emerged from Taiwan’s earlier ethnopolitical movements. These rhetorics allowed them to critique assimilationist policies while asserting that marriage migrants and their children were internal members of Taiwanese society—advancing a bottom-up form of multiculturalism. A landmark example was the 2003 renaming campaign initiated by The Awakening Foundation, replacing derogatory terms such as “foreign bride” with “new immigrants” (新移民), a name chosen by the migrants themselves. Echoing the 1980s Indigenous Name Rectification Movement, this campaign symbolised dignity and a collective social situation that transcended the state’s division between “foreign” and “Mainland” spouses, opening space for broader immigrant inclusion.

These strategies drew strength from Taiwan’s post-authoritarian transformation. Following democratisation in the 1990s, Indigenous Peoples were constitutionally recognised, and Taiwan began to portray itself as a multicultural society. Multicultural education reforms (Li 2017) and political discourses of the “four major ethnic groups” (Indigenous, Hoklo, Hakka, and Mainlander) popularised multiculturalism as a moral rhetoric of democracy, even if its engagement with social justice remained limited (Chang 2002). Within this context, immigrant advocates appropriated this politically legitimate language of diversity to reshape public consciousness and reverse the marginalisation of marriage migrants long depicted as subordinate “others”.

In 2004, AHRLIM organised “In the Mother’s Name–Seeing Taiwan’s New Immigrants/Residents”, an initiative aimed at normalising the languages and cultures of marriage migrants as part of everyday Taiwanese family life. Advocacy narratives emphasised the mother–child bond, highlighting how systemic discrimination against immigrant mothers also shaped their children’s life chances. It further emphasised that the human rights precarity faced by these mothers under institutionalised inequality is the true intergenerational harm affecting their children and the whole transnational marriage family. These early campaigns laid the groundwork for reimagining marriage migrants as part of Taiwan’s internal diversity rather than as external dependents.

The Blind Spot of Top-Down Immigration Multicultural Activities

In the early 2010s, the Ministry of Education’s Republic of China Education Report identified “respect for diversity” and “care for the disadvantaged” as the foundations of multicultural education. Two years later, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Education launched the “New Immigrants Torch Project” (新住民火炬政策), which applied a principle of affirmative measures to justify additional educational resources for marriage migrants and their children.

Although this top-down approach may appear progressive in its rhetoric, it presupposes disadvantage as a condition for inclusion. Spouses from European, Northeast Asian, or other backgrounds considered non-disadvantaged rarely appear in these activities, leading to selective labelling. Chinese marriage immigrants, perceived as having no language barriers, are marginalised in multicultural programmes, while Southeast Asian immigrants are more clearly included because Torch Program activities—such as mother tongue singing competitions—focus on Southeast Asian languages and cultural symbols.

In this way, immigrant multiculturalism takes on a performative character: its imagined benefits lie in enhancing the cultural confidence and self-identity of immigrants and their children and in fostering respect and appreciation within the local community. However, because these policies fail to recognise the heterogeneity of second-generation experiences and provide sufficient cross-cultural sensitivity education for the general public, they have been criticised for reducing multiculturalism to a narrow display of exoticism.

How State Development Strategies Shape Multicultural Discourse

Taiwan’s state development strategies have been another key force shaping immigrant-integration discourse. Constrained by its contested sovereignty and situated within volatile regional geopolitics, Taiwan has increasingly incorporated migration into its strategies for international economic positioning and geopolitical crisis management.

From the late Ma Ying-jeou administration to the late Tsai Ing-wen era, central ministries began reframing the Southeast Asian cultural backgrounds of transnational marriage families as valuable resources for cross-border talent cultivation. With the introduction of the New Southbound Policy in 2016, multiculturalism was rearticulated as a form of soft power that linked immigration to Taiwan’s southbound engagement strategy.

Under this new framework, Southeast Asian marriage migrants and their children were celebrated as “national human resources” and “vanguards of southbound engagement”. The rapid expansion of overseas training programmes and special university admissions repackaged the cultures of Southeast Asian immigrants as marketable cultural capital.

Immigrant cultures were thus instrumentalised as extensions of Taiwan’s diplomatic and trade agendas. The offspring of Southeast Asian marriage migrants were encouraged to display bilingual and cross-cultural strengths. In contrast, the children of PRC-spouse families—whose parents are subject to a special citizenship regime and to cross-strait political sensitivities—were further marginalised and rarely fit within narratives of celebratory multiculturalism. In the past two years, as China-related security threats intensified, the citizenship legitimacy of PRC marriage immigrants has faced public debate and legislative discussions. For example, proposals to lower the minimum residency requirement for naturalisation of Chinese marriage migrants—from the current six years to four years, equal to that for other foreign spouses—have sparked public debate. Civil society groups worry that such changes could encourage a rise in Chinese marriage migrants. In some anti-immigrant discourse, second-generation children of Chinese marriage migrants are even portrayed as “tools of China’s population infiltration”, framed as potential threats to national security. In early 2025, a renewed government review concerning whether naturalised citizens of former Chinese nationality had submitted proof of household registration cancellation in China affected not only marriage migrants but also second-generation individuals born in or previously registered in China. Although second-generation youth with PRC-immigrant backgrounds constitute 48% of Taiwan’s New Second Generation (MOI, births by parental nationality), they find themselves in a dilemma and a marginal position within the multicultural discourse of immigrant integration policy.

Generational Gaps and Unequal

Different cohorts of the New Second Generation have encountered sharply divergent realities. Earlier generations grew up under problem-population discourses, whereas younger cohorts, especially those coming of age after the New Southbound Policy, face high expectations to embody multicultural advantage.

In the absence of a comprehensive framework for immigrant integration, Taiwan’s multicultural discourse has oscillated with shifts in advocacy energy and transregional geopolitical tides. On one hand, it symbolises Taiwan’s democratic embrace of diversity; on the other, it often reproduces new inequalities. Those who benefit are typically the “displayable differences”—groups whose cultural traits can be utilised to demonstrate policy achievement as state resources cluster around visibility-oriented programmes, internal hierarchies within immigrant communities deepen, reinforcing stereotypes rather than dismantling them.

Class-Based Inequalities of Immigrant Integration

After years of advocacy, AHRLIM achieved early successes in reforming Taiwan’s citizenship regime and has continued to serve as a coalition uniting diverse immigrant and migrant worker groups around shared goals in immigration governance. In recent years, as the life trajectories of immigrants and their second-generation children have evolved, the themes of Taiwan’s immigrant rights movement have also become increasingly diverse—expanding beyond cultural equality to encompass welfare equality. For example, the TransAsia Sisters Association in Taiwan (TASAT) advocates for healthcare rights for middle-aged and older immigrants. Taiwan Immigration Youth Alliance (TIYA) promotes cross-cultural sensitivity training for teachers and advocates for the enactment of anti-discrimination laws.

In 2024, the Legislative Yuan enacted the New Immigrants Basic Act (新住民基本法), which expanded the definition of “new immigrants” to include white-collar economic migrants and intermediate-skilled workers. This broader framework marks an important milestone, marking the first time Taiwan incorporated the protection of immigrants’ fundamental rights into the constitutional principle of multiculturalism. However, the government and civil society remain divided over the law’s broad definition of “new immigrants”. Whether multicultural discourse marks a genuine turn as rhetorical cover—concealing class-based inequalities in immigrant rights and welfare—remains an unresolved question in Taiwan’s immigration governance.

Chien-Ping Liu is the Chairperson of the Taiwan Immigration Youth Alliance (TIYA) and Editor of the New Second Generation Voice column. This article is excerpted from part of her master’s thesis, “The impact of national development strategy and Civic Legacy on immigration governance: Comparison of policies and discussion concerning the second generation of marriage immigrants in Taiwan and Korea.”

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Engendering Mobilities: Migration, Memory, and Material Circulations‘.