Written by Yulia Nesterova (Yulia.Nesterova@glasgow.ac.uk).

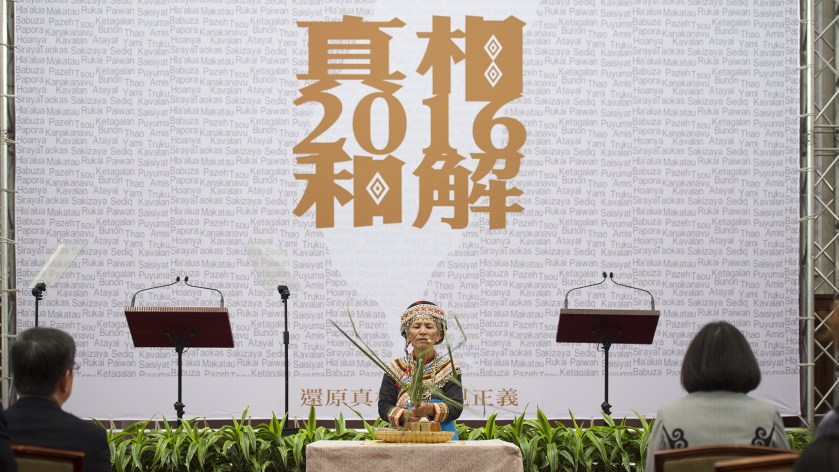

Image credit: An indigenous people’s representative performs a traditional prayer rite of the Bunun tribe before the ceremony starts. (2016/08/01) by Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan)/ Flickr, license: CC BY 2.0 DEED.

In the past 30+ years, Taiwan has made remarkable progress in transforming into a flourishing multicultural democracy and an example of a successful transition for the rest of the world.

Taiwan’s embrace of multiculturalism as a social ideal across institutions and policies to address inequities and injustices its diverse population has been facing sets it apart from countries struggling to accommodate diversity and face traumatic histories. This makes Taiwan an important country to learn from, but it also identifies further work needed to support its most vulnerable ethnic groups.

Multiculturalism in Taiwan

Taiwan’s multiculturalism has focussed on localisation (or ‘nativisation’ / 本土化) and democratisation of the country’s identity and development. In a multi-lingual and multi-ethnic country in which diversity and pluralism had been suppressed until the late 1980s due to colonialism and nationalism, this involved a rediscovery of local ethnic and linguistic diversity to establish a locally rooted national identity and culture for a peaceful multicultural and multi-ethnic coexistence and nation-building. As a result, a strong Taiwanese identity has emerged despite the country’s diverse ethnocultural background and minority groups’ (Hakka and Indigenous) mobilisation around their own political agendas (e.g., their cultural rights).

Multiculturalism was also chosen to remove the various social, political, academic, and economic barriers that Taiwan’s Indigenous groups have been grappling with due to colonisation, nationalism, and their legacies. The past three decades have thus seen the development of a powerful policy and legal framework to support Indigenous peoples. In 1992, the government amended the Constitution to officially recognise Indigenous peoples as “the people who lived here first” (Yuanzhuminzu), and in 1996, The Council of Indigenous Peoples was established as a ministry-level body. An array of laws and policies to protect their rights has been since introduced, including the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law (an Indigenous mini constitution), among many others.

As a successful implementation of Indigenous education to achieve these goals has become “an indicator of social progress”, two crucial policies were introduced: Indigenous Languages Development Act that recognises Indigenous languages as national languages, Indigenous Education Act that sets to support the revival of Indigenous languages, identities, cultures, and traditional structures and to develop culturally relevant education to support Indigenous learners’ success; and Indigenous Experimental School Policy that supports Indigenous-centred and -controlled education development.

These policies, laws, and processes are crucial for a country in transition, especially as Indigenous people, and youth in particular, place significant value on the revitalisation of Indigenous languages, cultures, and identities as a way to counter historical oppression and its remnants. But are they enough?

Is Multiculturalism Enough?

The multiculturalism discourse has received a lot of criticism. Whilst multiculturalism tends to be viewed as a silver bullet that can address and redress inequalities across diverse contexts, not only in Taiwan, research shows that the multiculturalism that we practice is still informed by assimilationist logic.

Indigenous people are expected to adjust to the dominant culture, whereas little accommodation is made to meet their needs. For example, whilst Indigenous learners have access to Taiwan’s high-quality education, these schools have a monocultural curriculum, pedagogies, learning environment, and overall institutional structure. Such education may be seen as meaningful as it is grounded in the knowledge, worldview, values, and conceptions of the Taiwanese people of Han Chinese origin. Schooling thus leads to Indigenous learners’ lack of motivation to study, feelings of isolation, and loss of a sense of belonging, intergenerational ties, and cultural continuity. And yet, the blame for their low academic achievement and high drop-out rates is placed on their cultural difference (often referred to as cultural deficit) rather than on the system.

New innovations in the form of Indigenous-led schools and Indigenous-centred curricula and textbooks have also emerged to support the Indigenous population. On paper, these projects give power, ownership, and control to Indigenous people. In practice, leadership positions are occupied by non-Indigenous who offer little support to Indigenous people to decolonise and, instead, overfocus on ticking boxes at neglect, creating processes in which Indigenous communities participate, lead, and contribute.

Additionally, a level of discrimination and even racism persists in the society. One explanation for this is that multiculturalism only incorporates sanitised and tolerable Indigenous content, such as Indigenous environmental knowledge and values. Indigenous history, such as military subjugation and harsh assimilationist policies in place between the 17th century and the late 1980s, is left out.

This status quo does little to redress existing injustices and, instead, reproduces deeply entrenched inequalities and vulnerabilities. After all, in contexts where significant damage to Indigenous identities, cultures, ways of life, traditional structures, and languages has been done, surface changes can do very little. Importantly, it is not the laws and policies that are a problem – they are comprehensive and empowering. However, there is not much effective action to implement them and to transform unjust structures, which, we know, are largely resistant to change.

This unwillingness or resistance to fundamental change can be explained by the colonial mentality still evident in Taiwan among non-Indigenous and even Indigenous people who internalised it. Colonial mentality continues to shape how institutions work and what they reproduce and determines whether and how policies are implemented. My own research with Indigenous people showed that they simply do not believe that their concerns are seen as serious or urgent; hence, policies’ partial implementation.

As Sra (Bo-Jun Chen) explains, the “ignorance of our history poses [s] a far greater threat to us than the plundering of our resources and hazards to our lives.” Because of this, Sra maintains, Indigenous youth are “committed to overcoming obstacles influenced by colonialism.”

Decolonisation of Taiwan’s multicultural vision is thus necessary, but what does that entail? And what has already been done in this direction?

Decolonising Multiculturalism

A significant step towards decolonisation was an official apology to the Indigenous peoples by then President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) in 2016 for the subjugation of the Indigenous population and the oppressive legacies they endure. Tsai referred to the Indigenous population as ‘Taiwan’s original owners.’

Subsequently, the Indigenous Historical Justice and Transitional Justice Committee was established. This process showed that the government recognises that to support the Indigenous population out of the cycle of vulnerability and marginalisation, there needs to be a fundamental change in the treatment of and resources provided to the Indigenous groups as well as the relationship between them and the state/ethnic majority.

Simply put, it requires redressing historical injustices and reconciliation.

For these processes to be successful and for the existing policies to be substantially more effective, decolonisation of education should become one of the central purposes. And the reason for this is that it is through education that we can deconstruct and get rid of the assumptions of Han Chinese civilisational superiority and of Indigenous inferiority and rebuild inter-group relationships.

The following are some of the ways to accomplish decolonisation. This list is not exhaustive, but it focuses on what’s important: getting to know each other, building trust, and overcoming the ‘lukewarm public support’ for transitional justice.

First, for the government and the public to become committed to supporting and resourcing Indigenous development, there needs to be an understanding of why this change is critical and urgent. Incorporating Indigenous history (and that of their colonisation) is a first step. What should go hand in hand with that is an exploration of the consequences and legacies of colonialism and nationalism. That is, Taiwanese people should understand the links between colonialism and continued racism against Indigenous people, their socio-economic marginalisation, and the fragmentation of their communities.

Second, inter-group relationships need to transform. This involves working on how Indigenous peoples are perceived and treated in society. For example, anti-racist education can help with transforming perceptions and attitudes towards Indigenous people and building a more equitable relationship between different groups. Also, introducing Indigenous values, knowledges, norms, and worldviews in more authentic ways can challenge harmful stereotypes, create more safe ways to engage with one another, and decolonise knowledge and meaning-making.

Third, inter-group partnerships need to change qualitatively. For example, Indigenous ways of engaging with others focus on having a meaningful process and on building rapport and trust. Partnerships between them and other Taiwanese groups need to move away from meeting deadlines and ticking boxes to be able to effect a sustainable change.

Fourth, it is not only non-Indigenous Taiwanese groups that may view Indigenous peoples through a racist lens. Indigenous people themselves can disregard their Indigenous identities and cultures as they see them in a negative light. A more holistic approach to revive and strengthen Indigenous languages and cultures in a non-essentialist way is thus needed.

Until these and other decolonial practices are put in place, the status quo will remain, and there will be no awareness that it needs to be challenged and dismantled. In the event that this continues, as Professor at National Dong Hwa University Awi Mona put it, it is “unlikely that Indigenous peoples will find remedies to injustices.”

Yulia Nesterova, PhD, is a Lecturer in International and Comparative Education and co-leader of Justice, Insecurity and Fair Decision-Making Interdisciplinary Research Theme at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. Her research focuses on minority/Indigenous rights, reconciliation, and education; peace and peacebuilding education; and community- and youth-inclusive peacebuilding. Prior to joining Glasgow, she was with UNESCO, working on peacebuilding and sustainable development. Yulia is an Associate Editor of the Diaspora, Indigenous and Minority Education journal.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Unsettling Multiculturalism in Taiwan‘.