Written by Dr Hannah Stevens & Dr Will Buckingham.

Image credit: the authors and Wind&Bones Books.

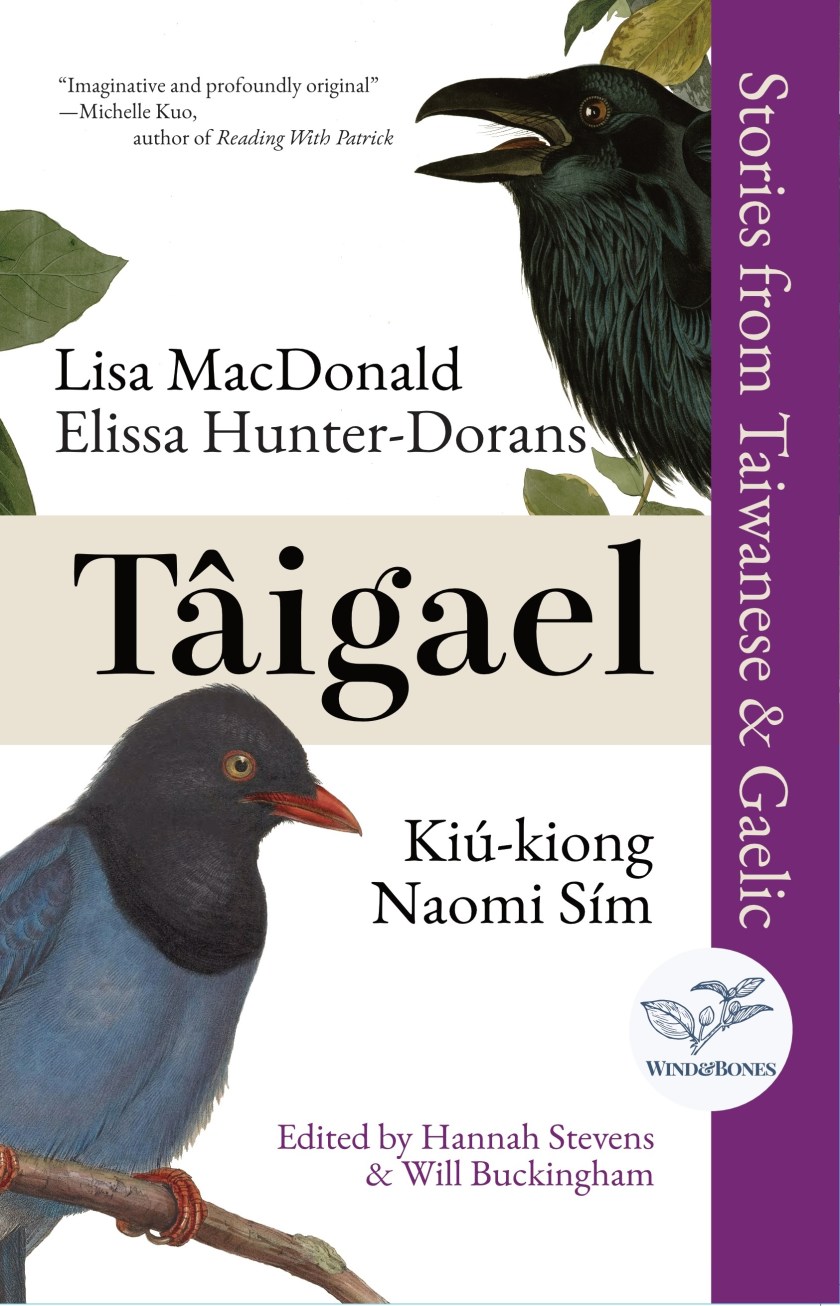

Why translate from Taiwanese to Gaelic and back again? What possible reason could there be to publish a book of translations between these two small languages? And what challenges are there in embarking on such an enterprise? Since the publication of Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic (Wind&Bones Books 2025), many people have asked us these questions. What, people have asked us, are we even up to?

Like many questions worth asking, these are questions with not one, but a myriad of answers. Here, in this special issue of Taiwan Insight, three of the writers involved in the Tâigael project share some of their own answers. And for ourselves, the answers we have given to this question have deepened and multiplied as the book has taken shape.

The idea first came to us when we attended the 2024 National Languages on Arts and Culture International Forum in Taipei. As recent immigrants to Taiwan from Scotland—and as writers ourselves—we were interested in the country’s extraordinary linguistic diversity. And, as the forum continued, we started to think more and more about the parallels between language minoritisation and revival not just in Taiwan, but also in Scotland. Perhaps, we thought, there was merit in the idea of a book of stories translated not just from smaller, minoritised languages into larger, dominant languages, but also between minoritised languages. Why should English, for example, or Mandarin, be the inevitable endpoint of translation? Couldn’t these larger languages simply be staging posts—inevitable, necessary perhaps—on a journey the ultimate aim of which was to build solidarity between the literatures and languages of minoritised languages?

For us, the idea was initially an experiment in building solidarity between writers in the two countries that we call home: Scotland and Taiwan. We pitched the idea to the Scottish Government’s Scottish Connections Fund and were awarded a small grant to kick-start the project. So, we brought together two writers from Scotland writing in Gaelic, and two writers from Taiwan writing in Taiwanese. Our writers in Scotland were Lisa MacDonald and Elissa Hunter-Dorans; meanwhile, in Taiwan, our writers were Kiú-kiong and Naomi Sím. The four stories were all startling and powerful works of fiction—by turns fierce, subtle, funny, engaging, intriguing and moving. But this was only the beginning of the process. We then set about collaboratively translating between these minoritised languages, using Mandarin and English as intermediary languages. Lisa and Elissa translated each other into English, while Naomi and Kiú-kiong translated each other into Mandarin. Additional translation was conducted by Shengchi Hsu (from English to Mandarin) and Will Buckingham (from Taiwanese to English, in collaboration with Kiú-kiong and Naomi Sím). Working collaboratively in this way, each of the four writers’ stories was eventually translated into four languages: Gaelic, Taiwanese, and the intermediary languages of English and Mandarin.

As the process of translation—a chain that led from Taiwanese Tâi-gí to Mandarin, from there to English, and then to Gaelic, before turning back again in the other direction—proceeded, the enormity of the task we had set ourselves began to dawn on us. While we all juggled multiple drafts of the stories and translations, in this back and forth, we found ourselves asking ever-deeper questions about the aesthetic, political and technical challenges, risks and opportunities of translation, particularly between minoritised languages.

These questions could perhaps fill another book. But in this special issue of Taiwan Insight, we are going to hand over to three members of the writing and translation team to share their own reflections on this process. The essays that follow not only throw more light on the questions with which we opened— Why translate from Taiwanese to Gaelic and back again? What possible reason could there be to publish a book of translations between these two small languages?—but also ask some compelling questions about translation, language minoritisation, literature and the politics of resistance.

Elissa Hunter-Dorans’ essay starts by talking about discovering unexpected points of kinship between the cultures and languages of Taiwan and Scotland. Hunter-Dorans is struck, as we were, by the recurrent presence of mothers and grandmothers in the stories in the book. What, she asks, is this preoccupation with the theme of the maternal, and how does this relate to the idea of a ‘mother tongue’? In answering this, Hunter-Dorans argues that marginalised languages have historically been shaped and sustained by oral traditions, transmitted through familial networks of care. Through this transmission, she proposes, languages take on a form of intimacy, a tenderness that can be said to inhere in the language itself. If this is the case, Hunter-Dorans asks, then what would it mean to think of a mother tongue as itself maternal? And how can minoritised languages act as a bearer of this legacy of care, even when languages are no longer transmitted across generations, where, for example, mothers and grandmothers are no longer the ones who pass on the language in the home? Hunter-Dorans proposes that under these conditions, perhaps the language itself can take on a kind of surrogate motherhood, sustaining those who rediscover it. ‘The creation of new literature in minority languages,’ she writes, ‘is therefore not only creative but crucially generative […] Like a maternal voice, it protects, teaches, and guides us as new speakers of these tongues.’

Naomi Sím tackles questions of mediation, asking about the risks and challenges of translating between minoritised languages. In Tâigael, the stories are translated into four languages, with Mandarin and English forming crucial bridges between Gaelic and Taiwanese. But, as Sím acknowledges—and as we were aware from the very start—this risks simply replicating the hierarchies between more dominant and smaller languages. To explore this unease, Sím draws on survey data from readers at the Taiwanese language launch of Tâigael (which we were fortunate enough to attend) to argue that—if we are alive to the risks—this ‘bridging’ of minoritised languages through more dominant languages, although perhaps compromised, may be ultimately worthwhile.

During our first book event in Tainan, Kiú-kiong argued that Tâigael could be considered a contemporary Rosetta Stone—a document that connects less familiar languages through the mediation of more familiar languages. Drawing on this idea, Sím coins the term ‘rosettation’ to describe the strategy used in the book: that of translating between minoritised languages via shared majority languages. Sím writes, ‘Taking its name from the Rosetta Stone, rosettation seeks to centre smaller languages, while acknowledging the practical limits of translation by bridging them through intermediary ones.’ She ends by arguing that the practice of rosettation can open up important conversations and has the potential to expand far beyond this one collection of stories in Gaelic and Taiwanese.

Finally, Lisa MacDonald, in her essay ‘Orchids in the Wild,’ asks about the limits of translateability. How does one translate chhùi-lân (翠蘭)—which we translated into English as ‘Emerald Orchid’— from Taiwanese to Gaelic? What images does this conjure in both linguistic contexts? What are the cultural connotations, the echoes of meaning, which are found when the orchid takes root in Taiwan, or in Scotland? After all, lân (蘭) may refer to an orchid. It is conventionally translated as such in English. But the Taiwanese term may refer to a wide variety of other fragrant plants. When is an orchid not an orchid? Through grappling with the languages of Taiwan and Scotland, and their rootedness in different ecologies, MacDonald’s essay returns to themes of care, intimacy, and fidelity to the specifics of the worlds across which we translate. For MacDonald, there is a triple fidelity to which the translator needs to attend: not only to both languages and both cultures, but also to the ecology of the story itself. Translation, MacDonald argues, is not a mechanistic process of substituting one thing for another, but a search for a deeper faithfulness, a deeper rootedness. And in its refusal to settle for easy or glib answers to the challenges of moving between contexts, there is a defiant form of resistance.

Having read through these essays, we find ourselves re-reading Tâigael with new eyes. The book may now be published, but—for us, at least—the conversations and trains of thought to which it has given rise seem to be just beginning. We write in the introduction to the book that translation makes the world larger, that it expands the possibilities for thinking and feeling. But the essays collected here also show how translation also multiplies questions and challenges. And perhaps it is in responding to these questions and challenges that we can open up new pathways, new forms of literary expression, new collaborations, and new forms of solidarity.

Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic is published by Wind&Bones Books (2025). The free-to-listen audio is available at https://taigael.com (go to the Stories & Storytellers page). The website also has links to buy the book in Taiwan, Scotland and elsewhere. Or the book can be purchased directly from https://books.windandbones.com.

Dr Hannah Stevens holds a PhD in creative writing from the University of Leicester. She co-directs Wind&Bones Books and has published fiction and nonfiction globally. Her most recent book is the short story collection, In their Absence (Roman Books 2021). She is on the visiting faculty at Parami University, Myanmar, and is currently based between Taiwan and the UK.

Dr Will Buckingham is co-director of Wind&Bones Books. He holds a PhD in philosophy and is the author of multiple books, most recently Hello, Stranger: Stories of Connection in a Divided World (Granta 2021). He is on the faculty at Parami University, Myanmar.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic‘.