Written by Naomi Sím.

Image credit: author.

In contemporary Taiwan, the renaissance of local languages has led to a growing interest in translating classical world literature. Works such as The Little Prince, Pride and Prejudice and 1984 have been translated from English and French into Tâigí, also known as Taiwanese Hokkien. These globally dominant languages have long shaped the social, political, and cultural landscapes of native tongues, in Taiwan and elsewhere. Yet a critical question arises: does promoting Tâigí mainly through translations of dominant works risk further marginalising Tâigí, and other minoritised languages worldwide? If so, what alternatives might enable them to communicate in these languages with one another?

To respond to the questions, on 12 July 2025, Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic was launched at the Lâm-tō͘ Project × Café Nothing, an independent bookstore in Tainan, bringing together two endangered languages from opposite sides of the globe—Tâigí and Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig). Both languages have experienced long histories of suppression, and yet both remain vital vehicles of living traditions. The event at Lâm-tō͘ Project × Café Nothing gathered Taiwanese writers, who also served as translators, alongside editors and readers, to celebrate a collaboration between two minoritised languages. Following the launch, I conducted a survey with 13 participants to understand how Taiwanese readers responded to this experimental method of rosettation.

Through asking about their associations between language and cultural identity, their attitudes toward intermediary (multi-step) translation, their current ability to read Tâigí, their level of interest in Tâigí literature, and their motivations for supporting rosettation publications, the responses revealed not only linguistic anxieties but also deeper concerns surrounding fairness, memory, and cultural preservation within Taiwan’s multilingual context.

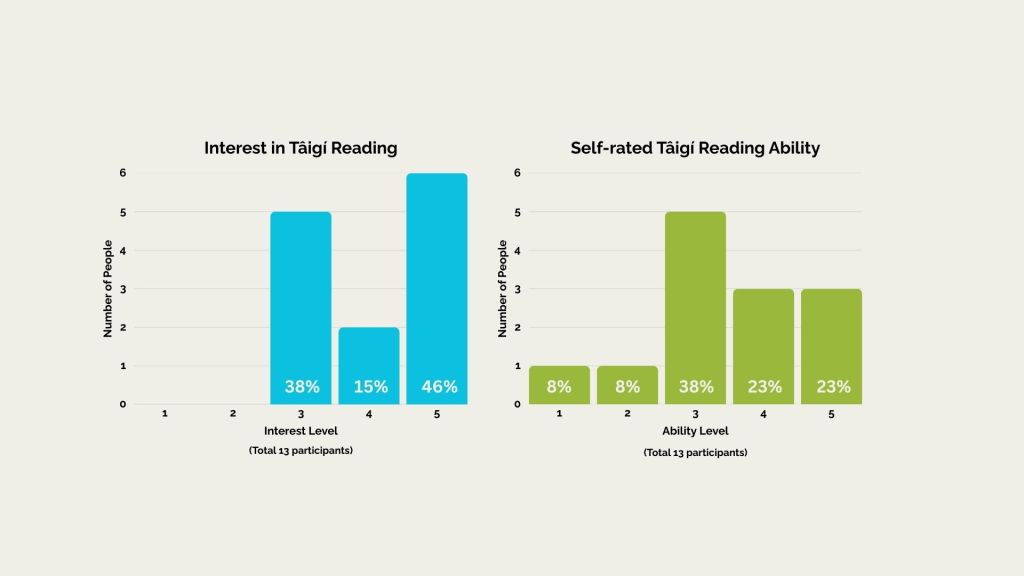

Interest vs. Ability

A majority of participants rated their reading ability in Tâigí at an intermediate level (38% at level 3), with fewer rating themselves as highly fluent (23% at level 5). Notably, interest in reading Tâigí stories was higher than ability: 46% of respondents rated their interest at level 5, which is the highest possible, suggesting strong enthusiasm for Tâigí content even among those who do not yet feel confident reading it.

This gap between interest and ability highlights the potential role of rosettation in expanding access to Tâigí literature, with bilingual or multilingual versions, particularly when paired with audio formats, as this allows rosettation to act as both a bridge and a learning tool for those hoping to deepen their engagement with the language.

Reception of Rosettation and Translation Concerns

While 77% of respondents expressed concerns about meaning being lost through multiple steps of translation, nearly all would still support future rosettation publications. Many acknowledged that, in the absence of fluent bilingual speakers between two minoritised languages, indirect translation may be the only way to foster connection and mutual understanding. Others reflected on how rarely Tâigí literature engages with other minoritised cultures, noting that rosettation introduces a new and valuable model of storytelling exchange.

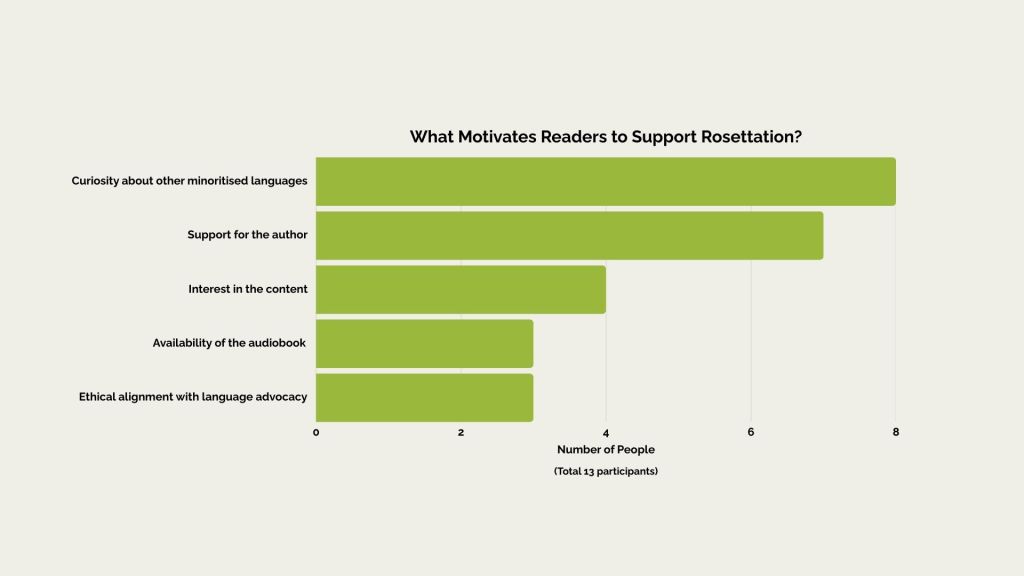

What Motivates Readers to Support Rosettation?

When asked what factors would motivate them to purchase a rosettation book, participants could choose up to three options. While not all selected the full three, the chart below presents the top five most frequent reasons, with the leading response being curiosity about another minoritised language. This underscores how rosettation can spark interest not only in Tâigí, but also in languages like Gaelic, and potentially other local languages. In this Taiwan context, this may include languages such as Hakka and Amis, and globally, might include languages such as Sámi or Māori.

Seven respondents said they were motivated by author recognition; in other words, they had prior experience of, or our knowledge of, the authors in the collection. This points to the role of trust and community in supporting experimental formats. Four were drawn by the creative content itself, recognising that rosettation is more than a linguistic technique, but also a literary form. Three participants said the availability of an audiobook version influenced their willingness to buy, and another three appreciated that part of the proceeds would be donated to language revitalisation efforts.

These motivations suggest that readers see rosettation not just as a form of translation, but as a layered experience that combines ethical, educational, and emotional value.

A Quadrant of Attitudes: Reader Personas

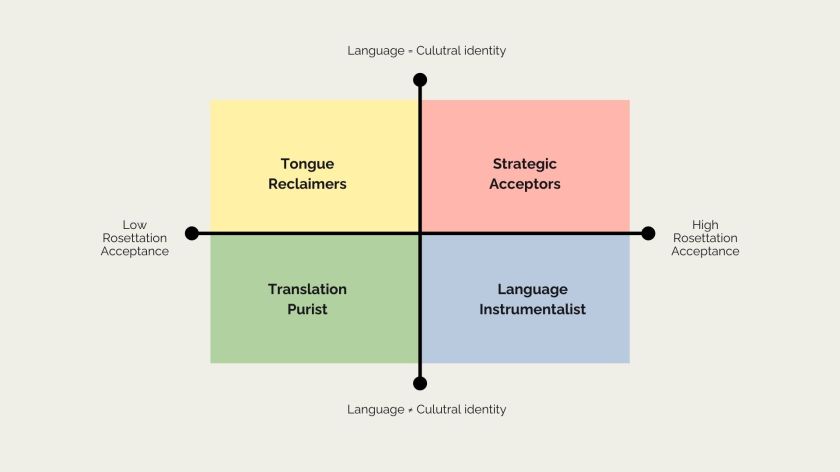

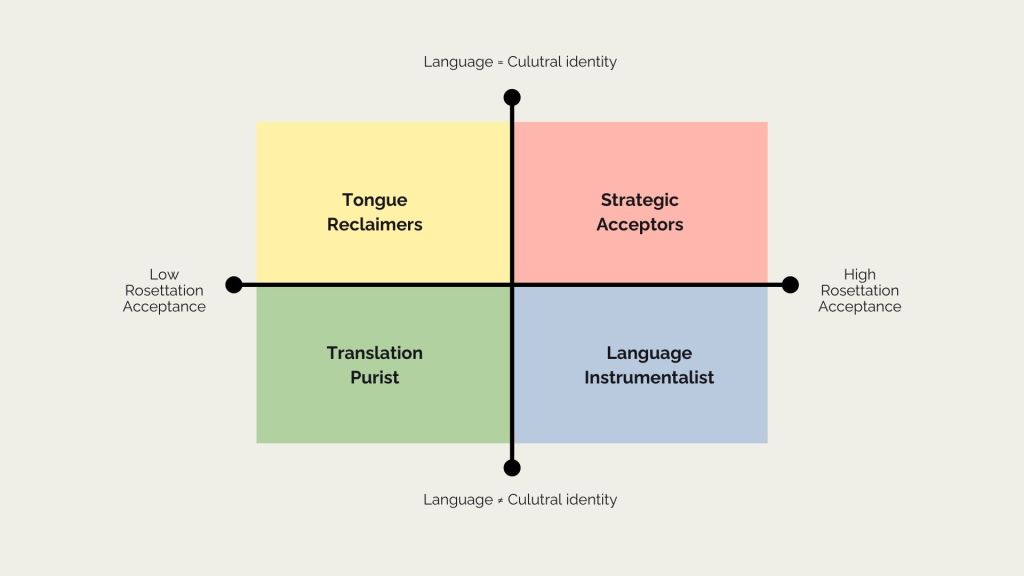

To identify where potential readers might fall in relation to rosettation, a quadrant was designed. The X-axis measured openness to rosettation, while the Y-axis reflected how strongly readers linked language to cultural identity. Although most event participants were already interested in rosettation, limiting the extent to which these results can be generalised, this model still serves as a valuable tool for audience segmentation. It allows publishers, educators, and authors to understand where a reader stands, and most importantly, what they need in order to engage with a rosettation text.

The framework revealed four distinct reader types: Strategic Acceptors see rosettation as a pragmatic tool for amplifying marginalised voices. While they are aware that some intermediary languages have oppressive histories, they focus on the broader picture, using translation to challenge power asymmetries in global discourse and give minority languages a global stage. Tongue Reclaimers, by contrast, strongly associate language with cultural identity and are sceptical of rosettation. They wish to protect the “original flavour” of stories and are especially wary of using Mandarin in Tâigí contexts due to historical trauma. Language Instrumentalist view language as a functional tool rather than a core part of identity. Their priority is content accessibility and cultural engagement. As long as it increases readership and visibility for minoritised literatures, they support any translation method, including rosettation. Translation Purists are sceptical of intermediary translation, especially when it passes through multiple layers. They prioritise textual fidelity and are concerned that each translation step distorts meaning, believing the final version is diminished if translators lack access to the original source text.

Tensions Around Mandarin

Rosettation was generally well-received by participants at the book launch event. However, one Taiwanese attendee, who is a Tongue Reclaimer, raised a critical question: why was Mandarin used as an intermediary language when all the team members were already fluent in English?

This concern stemmed from Taiwan’s complex linguistic history. During the martial law era, Mandarin was strictly enforced as the national language. Local tongues such as Tâigí, Hakka, and various Indigenous languages were marginalised, leading to stigma and intergenerational language loss. For many Taiwanese, Mandarin is not just a tool for communication but a symbol of cultural suppression.

Editor Will Buckingham later explained that the inclusion of Mandarin was a matter of structural balance. Since both Tâigí and Gàidhlig have experienced linguistic oppression by Mandarin and English respectively, using only English as a bridge would create an imbalance in the rosettation chain. Including Mandarin, in this case, was meant to reflect a symmetry of past struggles, particularly from the Gaelic side.

However, he added that this approach might not apply universally. In cases where neither language in the rosettation process had been historically suppressed by English, such as between Ainu and Amis, using only English as the intermediary language (or any other shared language) could be more politically and emotionally appropriate.

Implications for Rosettation Publishing

The Tâigael experiment opens up possibilities for a different kind of publishing in Taiwan. Instead of relying on the conventional pipeline where dominant language literature flows in and local literature flows out, rosettation allows for lateral connections among minoritised communities. These connections help them to see each other not as isolated speakers of niche languages but as part of a global mosaic of resilience.

That said, we must tread carefully because reader trust is fragile. Publishers using rosetattion methods should make the translation process transparent. This could include side-by-side versions or paratexts explaining the steps taken. They must also be sensitive to local emotions around intermediary languages like Mandarin.

Commercially, the market for such works remains small but potentially impactful. Cultural grants, academic institutions, or language revitalisation programmes could support these books. They can also offer rich material for literature workshops, language learners, and immigrant communities.

Rosettation as Literary Strategy

Ultimately, rosettation is not about achieving perfect equivalence. It is about building a bridge where none existed and accepting the imperfections of translation in order to amplify marginalised voices.

In our context, it was also about coming to terms with Taiwan’s linguistic past and imagining a multilingual future. Rosettating stories between Tâigí and Gàidhlig not only brought two minoritised languages into dialogue but also sparked critical conversations among readers about memory, fairness, and how we carry meaning across cultural gaps.

Future projects could explore rosettation between other pairs, such as Pinayuanan and Māori or Hakka and Sámi. With thoughtful structure and mutual respect, rosettation can evolve from a workaround into a movement.

All in all, rosettation is not merely translation, it is a constellation of love letters scattered across time, awaiting to be read by future generations who will trace the lines we left behind and find the way we once understood the world.

Naomi Sím (沈宛瑩) is a Taiwanese writer. She studied Communication Design as an undergraduate and is now a master’s student in Creative Industry Design. She has twice received the Tâi-gí Literature Award for short stories. By applying design thinking to creative writing, she explores ideas of identity, memory, and culture. Her stories often use humour and satire to reflect on social issues and the challenges of modern life.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic‘.