Written by Chee-Hann Wu.

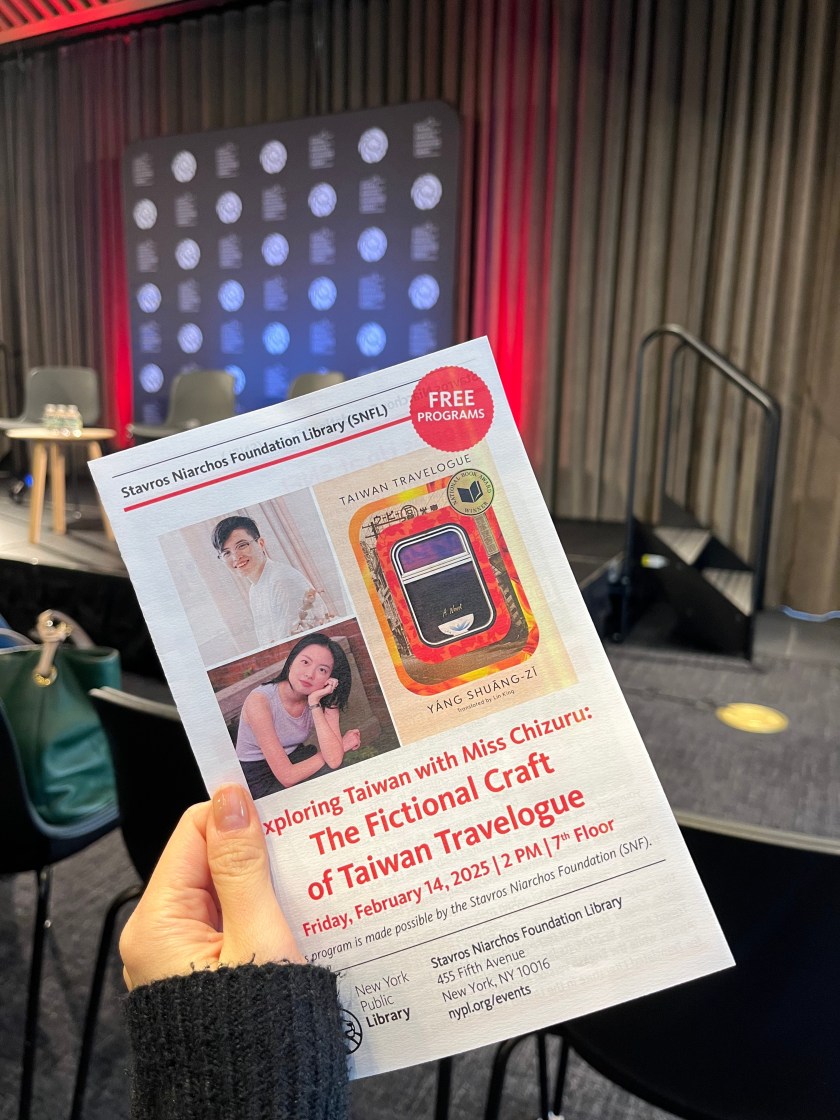

Image credit: Yang and King’s book talk on 14 February 2025 at NYPL by the author.

Taiwan Travelogue (2020/2024), the winner of the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2024, tells the story of young Japanese novelist Aoyama Chizuko’s (Chi-san) journey to Taiwan with her Taiwanese translator O Chizuru (Chi-chan) during Japanese colonization. It documents Chizuko’s tour of Taiwan and her encounter with the island’s various cuisines. The book, written by Taiwanese novelist Yang Shuang-zi and translated by Lin King, was first published in Mandarin Chinese in 2020, and the English translation was available in 2024.

Yang Shuang-zi and Lin King, resembling Chi-san and Chi-chan’s travels across Taiwan, kicked off a book tour in February 2025 with eight different talks in Southern California and New York City. This article documents some of the inspiring moments in the book talks at the New York Public Library (14 February) and the University of California, Irvine (18 February), in conversation with the novel itself and materials about the other talks.

A Travelogue or A Historical Fiction?

As you flip through the book, the first thing that always catches your eye is the extensive footnotes. Taiwan Travelogue can be said to be a historically heavy, well-researched historical novel, especially in its detailed descriptions of the architecture, cuisine, and culture of the 1920s and 30s Taiwan under Japanese colonisation. The footnotes are used to further explain culturally and historically specific terms and contexts. In the English version, the footnotes are a joint effort of Yang and King. In addition to the footnotes already included in the Chinese version, King added more to help English readers better understand the historical background of the novel and to differentiate between the multiple languages (such as Mandarin Chinese, Hakka, Taiwanese Hokkien, and Japanese) in the original novel. In order to integrate extensive footnotes more seamlessly into the narrative, a unique literary choice was made when Taiwan Travelogue was first published in Chinese, which led to an unexpected reception and controversy.

In fact, in this original Chinese version, Aoyama Chizuko, the “novelist-traveller,” was listed as the author on the book cover, while the “actual author” of the novel, Yang Shuang-zi, playfully listed herself as the translator. Readers were led to believe that they were reading a Chinese translation of a historical text, a travelogue, originally written in Japanese by Aoyama during the colonial period. It was later revealed that the novel adopted a nesting doll narrative and was actually a historical fiction instead of a genuine translated historical text. In addition to the above premise, the book’s publisher, Springhill Publishing, was mostly dedicated to publishing non-fiction works, further convincing readers that Taiwan Travelogue was not fictional.

The literary and advertising choices became controversial, causing dissatisfaction among some readers and even sparking a debate on publishing ethics. Being asked about her thoughts, Yang explained in a book talk that this was a literary strategy to incorporate footnotes into the writing. Springhill Publishing also released a statement explaining that this was their initial marketing strategy and a “literary game” and that there were clues in the book and beyond. They acknowledged the issues involved in such a literary innovation and experiment and hoped that the decision would not detract from the intent of the novel. In the English translation, the official title of the book is Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel, which sidesteps the controversy. King also explained that this is one of the traditions in English literature and a choice that both she and the editor agreed to.

Queer Literature

After Taiwan Travelogue won the National Book Award, though I had already read the original version, I went to a major indie bookstore in New York, hoping to pick up an English copy. As I browsed through the East Asian literature, award-winning books, and translated fiction sections, I was surprised to find it among the books in the “LGBTQIA+ PRIDE” category. When I first read the novel in Chinese, the possible unnameable romantic feelings between Chi-san and Chi-chan were clearly evident, but that was not what made the book stand out to me. It was interesting to see US bookseller Barnes & Noble calling this novel “a story within a story about two queer women and the colonial history of Taiwan”. In an interview with Lin King, Hairol Ma also expressed that she “read Taiwan Travelogue as a love story that is burdened by prejudice and complicated by colonial power dynamics.”

When asked this question about whether Taiwan Travelogue is queer literature, Yang and King directed it to the publicist of the publishing house, who happened to be present at the NYC book talk. The publicist said that it was not their intention to market the book as such and left it up to individual interpretation. However, they could see it as an effective marketing strategy to better introduce Taiwanese literature to English readers.

Beyond the strategic choice, the categorisation is understandable because Yang has been popular for her works about romantic relationships between two women, such as the novel Seasons Of Bloom (2017) and the short story collection Blossoming Girls of Gorgeous Island (2018). Yang’s work has often been referred to as yuri (lily) literature, a genre derived from Japanese media that focuses on intimate relationships between female characters. Some equate yuri with girls’ love (GL), while Yang embraces a broader definition: Yuri is about female relationships, including friendship, sisterhood, romantic, and even competitive relationships. She explained in an interview that “apart from romantic and competitive relationships, women’s kinship is extensive and complicated. Such a notion can also be seen in the relationship, power dynamics, and colonial hierarchy between Chi-san and Chi-chan, the Japanese novelist and her Taiwanese translator.

Yang further explained in the book talk that the Japanese colonial period was the first time in Taiwan’s history that women entered the public sphere, including greater access to education. However, the historical narratives continue to be masculine, where women’s voices are marginalised and unheard. It was as if the notion of identity politics was exclusive to men. Yuri provides a valuable space for women’s voices and life experiences. It focuses on women’s self-growth and highlights female narratives in historiography. Yuri allows female subjectivity and desire to be seen.

Food is Politics

Yang has always been vocal about the political nature of her work and career, believing that every piece of writing has its own ideology. In Taiwan Travelogue, it is clear that the act of travel and tourism in the colony is political. Each food and culinary culture has its own political nature, influenced by Taiwan’s long history of migration and colonialism, reflecting unique temporalities, spatialities, and life experiences. As she wrote in a Facebook post, “I usually point out a core concept [in my talks], which is that food is very political, and there is no room for ‘food is just food and politics is politics’. Every dish on the Taiwanese table is a microcosm of Taiwan’s history.” An attendee at Yang and King’s book talk at the City University of New York asked, “You say that food is politics, history is politics, and even love is politics, but is it possible to be less political?” Yang replied that these are all human activities. As long as there were people involved, or more precisely, power dynamics involved, there was politics.

At the UC Irvine talk, Yang further introduced her “meme theory.” When people ask who Taiwanese are, “it may be more about ‘meme’ and less about your ‘gene.'” Genes emphasise lineage, but saying what kind of lineage is Taiwanese is not the most appropriate interpretation of “Taiwanese,” who have been colonised many times in recent history and have migrated from one place to another. In contrast, memes are a kind of identity and collectivity that is cultivated through cultural transmission, especially through viral transmission. The understanding of the culture and the country in Taiwan Travelogue was based on food and the accumulation of a certain kind of emotion (not only for individuals). This idea further underscores how food epitomises history, capturing and manifesting a unique sentiment that can be shared among Taiwanese people.

Food and travel are political because they reflect power, identity, and access. Politics influence and even control food production, distribution, and consumption, shaping national and cultural identities as well as people’s lived experiences. Likewise, railroads and trains are intrinsically symbols of colonial modernity that are not highlighted but yet inseparable from Chi-san’s travel in Taiwan. Essentially, Yang’s work responds to concerns that, from colonial histories to modern globalisation, what people eat and how they move reveals broader political connotations. Literature is also political, as is the act of writing itself.

In closing, I want to include a quote from the poet Joseph Brodsky that was used in the writers’ petition for Taiwan’s recent recall movement, initiated by Yang Shuang-zi: “As long as the state permits itself to interfere with the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere with the affairs of the state.”

Chee-Hann Wu is an assistant professor faculty fellow in Theatre Studies at New York University. She is drawn to the performance of, by and with nonhumans, including but not limited to objects, puppets, ecology, and technology. Her current book project considers puppetry a mediated means to narrate Taiwan’s cultural and sociopolitical development, colonial and postcolonial experiences, as well as Indigenous histories. Chee-Hann’s most recent work explores video games, VR and artificial intelligence through the lens of theatre and performance.

This article was published as part of a special issue on ‘Mapping Taiwan: Literary Paths and Real Journeys‘.